1. Signs of unhealthy relationships

2. The role of medical professionals in identifying domestic violence

3. Impact of domestic violence

4. Excursus: Outsiders as witnesses of domestic violence

5. General domestic violence indicators in adults

Spotlight on Gynaecology/obstetrics, Surgery & Paediatrics

6. Gynaecology/obstetrics – Frequent indicators

7. Surgery: Emergency room – Frequent indicators

8. Paediatrics – Frequent indicators

Spotlight on Dentistry: Identification of victims of domestic violence

9. Dentistry – Frequent indicators

Sources

Introduction to the topic

Welcome to Module 2 on “Indicators of domestic violence”. In this module you will dive into the wide-ranging health consequences of domestic violence, learn about its identification by gaining knowledge about indicators encompassing behavioural, physical, and emotional aspects. Moreover, the role of and impact on those witnessing domestic violence will be also presented in an excursus.

Medical professionals will find specialised indicators for recognising and supporting victims with a focus on gynaecology/obstetrics, in the emergency room (surgery), paediatrics and dentistry.

Learning objectives

+ Understand the multifaceted consequences of domestic violence on victims, families, and communities, including physical, psychological, and social impacts.

+ Acquire the skills to identify potential indicators and “red flags” – using behavioural, physical, and emotional cues.

+ Recognise the emotional and psychological effects of witnessing domestic violence, particularly on children, and understand the importance of creating safe environments for all family members.

+ Recognise the domestic violence indicators being specific for gynaecology/obstetrics, the emergency-room (surgery), paediatrics and dentistry.

+ Acquire the knowledge as dentist about indicators that may suggest domestic violence with a better understanding of the important role of the dental sector in supporting domestic violence victims.

1. Signs of unhealthy relationships

Some relationships can have a negative impact on our overall well-being rather than improving it. Some may even reach a level of toxicity, and it’s crucial to be able to identify warning signs.

These warning signs, often referred to as “red flags”, serve as indicators of unhealthy or manipulative behaviour. They are not always recognisable at first — which is part of what makes them so dangerous.

Toxicity can be present in all forms of close relationships e.g. between friends, at work with colleagues, between family members, or in romantic partnerships. 1

Please click on the crosses in the corresponding circles below each term in the illustration to find further information on red flags in unhealthy relationships.

2. The role of medical professionals in identifying domestic violence

“As health professional, you will be the first and only contact for many victims.”

Victims may not always want to report domestic violence to the police or speak to a counsellor of an NGO, and the dark field related to domestic violence (DV) is quite high. But victims, when they definitely need help because of injuries or due to long-term health consequences requiring medical treatment, will finally have to see a physician.2

In addition, due to other non-domestic violence related visits to the medical sector (e.g. control appointments at the dentist, diabetes management, skin cancer screening) they do have doctor’s appointments more frequently and at this point their physician/dentist might detect signs of domestic violence although it was not intended by the victims. 3

Consequently, healthcare professionals are often the first beside friends and family, who either hear about the presence of DV or they are the first ones recognising indicators and symptoms pointing towards DV. 4

Source: WHO, 2020

“Often victims do not talk about the violence that they are experiencing”

For more information see Module 1: the wheel of power.

Traumatic events like sexual abuse, domestic violence, elder abuse, and combat trauma have lasting physical and psychological effects, affecting how patients approach healthcare and preventive measures. Trauma-informed care shifts the focus from “What’s wrong with you?” to “What happened to you?”

In Module 3 you will find detailed information about communication.

3. Impact of domestic violence

“Experiencing violence or abuse by an intimate partner increases the risk of developing a mental health disorder by almost three times and the risk of developing a chronic physical illness by almost twice.” 5

Every victim is different and the individual and cumulative impact of each act of violence depends on many complex factors. While each individual will experience domestic violence uniquely, there are many common consequences of living in an environment with violence and/or living in fear. Often the short and long-term physical, emotional, psychological, financial and other effects on individuals are quite similar.

It is important to understand the effects of domestic violence on victims, because those effects are responsible for many indictors they present to us.

Please click on the crosses in the corresponding circles below each term in the illustration to find further information on the physical and psychological impact of domestic violence.

Please note that all the following lists are not exhaustive; it represents only a selection.

Case study – General practitioner’s practice

Sabrina is an accountant, 30 years old, married to a construction worker for 8 years now. She tells her primary care physician about her low energy level and headaches that have affected her for over a year. The headaches have gotten worse in the past month, affecting her mostly at the end of the day and she gets hopeless and feels down.

She has trouble sleeping and reports pain all over. She has been to several physicians in the past year but has not found anything that could help her. She has had blood tests, been prescribed painkillers, been advised to get more exercise and change her diet. She tells her physician that she desperately needs something to be done for her today as her husband is getting impatient with the lack of results.

Task for reflection

(1) Reflect on the importance of routinely screening patients for domestic violence, even when they present with seemingly unrelated symptoms.

Impact of domestic violence on a child (witnessing or experiencing)

“Some of the biggest victims of

domestic violence are the smallest.” 6

Please click on the crosses in the corresponding circles below each term in the illustration to receive further information on impact of domestic violence on children.

“The way childhood abuse and/or neglect is remembered and processed has a greater impact on later mental health than the experience itself.” 9

“People who have experienced challenging or traumatic experiences in their childhood are more likely to exhibit both physical and cognitive impairments in old age.” 10 In the following table you will find more examples of short-term and long-term impact of domestic violence on a child experience or witnessing domestic violence:

- Children who have experienced violence and have mental health problems (e.g. psychosomatic symptoms, depression, or suicidal tendencies), are at greater risk for substance abuse, juvenile pregnancy and criminal behaviour. 16

- Children may learn that it is acceptable to exert control or relieve stress by using violence, or that violence appears to be linked to expressions of intimacy and affection. This can have a strong negative impact on children in social situations and in relationships throughout childhood and in later life.

- Children may also have to cope with temporary homelessness, change of physical location and schools, loss of friends, pets, and personal belongings, continued harassment by the perpetrator and the stress of making new relationships.

Case study: Long-term impact of domestic violence

When Elyse, a 28-year-old nurse developed debilitating irritable bowel symptoms (IBS), she went to a new primary care physician. In response to the physicians detailed questions as part of initial assessment, Elyse told her that work was okay but she was having a few problems with her boyfriend. Sex was sometimes painful, but she tried not to show it. She had occasional migraines, her periods were heavy and painful and she was treated with antidepressants for 3 years in her early twenties. She was a binge drinker as a teenager. She’d only ever had one Pap smear 8 years ago and it was excruciating.

Tasks for reflection

(1) Which symptoms reported Elyse to her physician?

(2) Why do you think her symptoms may indicate the presence of DV currently and/or in the past?

Case adapted from The Medical Women’s International Association’s Interactive Violence Manual.

4. Excursus: Outsiders as witnesses of domestic violence

Given the short- and long-lasting negative impact on individuals living in an environment with DV and given that most never tell anyone, it is important that caregivers and family members, as well as neighbours or work colleagues which are potential witnesses of domestic violence don´t look away.

What would you do? 17

Tasks for reflection

(1) What are the “red flags” presented in this video that indicate that this is a toxic relationship where DV is present and someone needs help?

(2) What would you do?

The victim’s cooperation and consent are the most important prerequisites for intervening as a witness. An intervention by a witness can include talking to the victim, helping to access help services, or e.g. supporting the reporting of DV to the police.

Factors that may inhibit or encourage intervention by witnesses:

More information on the decisive factors for witness intervention in domestic violence can be found here: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/eiges-work-gender-based-violence/intimate-partner-violence-and-witness-intervention?lang=sl

5. General domestic violence indicators in adults

“Often, there are no visible indicators – therefore, it is crucial to ask the patient about domestic violence in the anamnesis.”

There is a whole range of indicators to serve as “red flags” to health professionals that a patient may be experiencing domestic violence. Some of these are quite subtle. Thus, it is important that professionals remain alert to the potential signs and respond appropriately. Please note that none or all of these might be present and be indicators of other issues. Some victims also drop hints in their interactions with health and care staff and their behaviour may also be telling.

Health care professionals should always ask about domestic violence when taken medical history. Find detailed information to communication in Module 3.

Victims rely on health professionals to listen, persist, and enquire about signs and cues. They need them to follow-up on conversations in private, record details of behaviours, feelings and injuries seen and reported, and support them in line with their organisation’s systems and local pathways.

Individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds may manifest their symptoms differently. Please remain conscious of your own perspective, biases, and stereotypes when communicating with a potential victim, as these factors can impact how you assess the symptoms. Find more information in Module 8.

Please note that none or all of these indicators might be present and be indicators of other issues, but they can serve as warning signs and a reason for increased attention and can point towards a history of DV.

Here, you will find a range of potential health indicators, psychological indicators for adults, and specific indicators pertaining to vulnerable groups. In the subsequent chapters, you will also encounter specific indicators tailored to gynaecology/obstetrics, surgery, paediatrics, and dentistry.

For better clarity, the indicators are categorised by colour: Yellow: General indicators; Green: Behavioural indicators; Blue: Psychological indicators.

Possible health indicators

- Chronic conditions including headaches, pain and aches in muscles, joints and back 18

- Difficulty eating/sleeping

- Cardiologic symptoms without evidence of cardiac disease (heart palpitation, arterial hypertension, myocardial infarction without obstructive disease)

Possible psychological indicators

- Emotional distress, e.g., anxiety, indecisiveness, confusion, and hostility19

- Self-harm or suicide attempts 20

- Psychosomatic complaints

- Sleeping and eating disorders (e.g. anorexia, bulimia, binge eating) 21

- Depression/pre-natal depression 22

- Social isolation/no access to transport or money23

- Submissive behaviour/low self-esteem 24

- Fear of physical contact 25

- Alcohol or drug abuse 26 27

Possible behavioural indicators

- Frequent use of medical treatment in various facilities

- The constant change of doctors 28

- Disproportionately long-time interval between the occurrence of injury and treatment

- Faltering response when being asked about medical history

- Denial, conflicting explanations about the cause of the injury

- Overprotective behaviour of the accompanying person, controlling behaviour

- Frequent absence from work or studies

- Evasive or ashamed about injuries

- Seeming anxious in the presence of their partner or family members

- Nervous reactions to physical contact/quick and unexpected movements

- Easily startled behaviour

- Easily crying when being asked questions

- Extreme defensive reactions when asked specific questions

Possible indicators which apply specifically to the vulnerable group of the elderly:

Possible indicators of domestic violence against the elderly

- Lack of basic hygiene

- Wet diapers

- Missing medical aids like walkers, dentures

- Bedsores, pressure ulcers

- Caregiver speaks about the elder as if he/she was a burden

Some healthcare workers worry that discussing suicide may trigger the person at risk, but in reality, addressing suicide can reduce their anxiety and foster understanding. If someone currently has thoughts or plans of self-harm or has a recent history of self-harm and is in extreme distress or agitation, do not leave them alone. Immediately refer them to a specialist or emergency healthcare facility.

Spotlight on Gynaecology/obstetrics, Surgery & Paediatrics

6. Gynaecology/obstetrics – Frequent indicators

6.1 Gynaecology

Possible indicators of sexual violence

- Injuries to the genitals, the inside of the thighs, the breasts, the anus

- Irritations and redness in the genital area

- Common infections in the genital area

- Pain in the lower abdomen and/or pelvic area

- Sexually transmitted diseases

- Bleeding in the vaginal or rectal area

- Pain when urinating or defecating

- Pain when sitting or walking

- Strong fears of examinations in the genital area; avoidance of examinations

- Severe cramps in the vaginal area during gynaecological examinations

- Sexual problems

- Self-harming behaviour

- Unwanted pregnancies/abortions (obstetrics)

- Complications during pregnancy (obstetrics)29

- Miscarriages (obstetrics) 30

6.2 Obstetrics

“When you are in an abusive relationship, there are two conditions when violence escalates: when you leave and when you are pregnant!” 31

“Homicide is a leading cause of death during pregnancy and the postpartum period.”

Lawn RB, Koenen KC. Homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women in US. BMJ. 2022 (2)

Source: Jamieson, B. (2020). Exposure to Interpersonal Violence During Pregnancy and Its Association With Women’s Prenatal Care Utilization: A Meta-Analytic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(5), 904–921. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018806511

Indicators during pregnancy

The following signs are indicators for domestic violence in relationships, however and not every woman who is anxious and/or nervous in the context of pregnancy, medical examinations and/or traumatisation during childbirth has violent experiences. Still, it is always important to look into the individual reasons why a woman experiences a trauma during pregnancy and childbirth, and it is important to ask women about domestic violence. For more information on how to communicate – see Module 3 and on medical assessment – see Module 4.

Midwives in particular have the opportunity to observe psychological signs of violence, as they have close and ongoing contact with patients during prenatal and postnatal care and often this can provide them with a deeper understanding of family dynamics.

| Red flags that should make you alert: · Missing many appointments · Miscarriage or refusal of home visits of heath personal or social workers · Overbearing or overly solicitous partner who is always present · Substance abuse of partner or patient |

Possible indicators of domestic violence seen in obstetrics 32

- Physical injuries/bruises: legs and/or vaginal area of women (-> victim of domestic violence or of rape)

- Missed appointments and non-compliance with treatment

- Frequent presentations to health settings or delay in seeking medical treatment/advice

- Overbearing or overly solicitous partner who is always present

- Injuries at different stages of healing or that don’t fit with the explanation given

- Unwanted pregnancy or termination of pregnancy

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- Sexual dysfunction

- Gynaecological problems

- Menstrual cycle or fertility issues in women

- Low maternal weight-gain

- Victim appears evasive, socially withdrawn and is hesitant

- Children currently referred to other specialists for behavioural/emotional or developmental problems

- Known history of abuse in family of origin

- Chronic pelvic pain

- Chronic irritable bowel syndrome33

- Miscarriage or other pregnancy complications

- Premature birth 34

- Stillbirth

- Fetal growth restriction (FGR)

Indicators related to the behaviour of the patient

- Restlessness, nervousness, fear and pain (specifically in connection with vaginal examination)

- Suicide attempts and thoughts

- Inadequate/delayed prenatal care

- Frequent hospital or clinic visits, especially when presenting with varied or unexplainable injuries or symptoms

- Substance use

- Presence of justified trauma with a confusing and contradictory history

- Continuous undefined health concerns and an anxious state that cannot be sedated with health reassurance

- Difficulty following health prescriptions, failure to respond to prescribed treatments

- Missing appointments

- Refusal of home visits by social workers, family or paediatric counselling staff

Behavioural indicators related to partner

- Controlling partner behaviours: overprotective/speak for the woman

- The accompanying partner is e.g. nervous, bad-tempered, aggressive, impetuous, arrogant, pushy

Possible indicators of domestic violence after birth

- Postpartum depression of mother

- Maternal death

- Difficulties bonding with the new-born

- Babies with low birthweight/injury/death

Task for reflection

(1) Reflect on the emotional toll that obstetricians, gynaecologists and midwives may experience when dealing with cases of domestic violence during pregnancy-

(2) What strategies could they use to cope with compassion fatigue and maintain their own well-being while providing support to victims?

Please click on the crosses in the corresponding circles below each term in the illustration to find some quotes of patients which may serve as indication that DV may be occur during pregnancy.

Case Study: Violence during pregnancy

Mandy was a 23-year-old patient currently 28 weeks pregnant. I attended her birth and have been her doctor since then. I knew her quite well as she had asthma and spent more than the usual time in my office. I also looked after her mother and sister and grandmother.

She did not do well in school and hung with the rough crowd. Although we had talked about contraception on previous visits, she was unreliable taking her birth control pills. Therefore, it was not a surprise to find her presenting to my office for pregnancy care. Her relationship was unstable but at present she was living with the baby’s father, an El Salvadorian immigrant involved in the drug trade. The pregnancy was progressing uneventfully until one day Mandy presented with facial bruising and abdominal pain.

Tasks for reflection

(1) What are possible indicator that in this case pointing towards the presence of domestic violence in the pregnant patient.

(2) Reflect on how domestic violence during pregnancy can affect both the physical and emotional well-being of the mother and the developing foetus. What are the potential complications, and how can they be addressed?

Case adapted from The Medical Women’s International Association’s Interactive Violence Manual.

7. Surgery: Emergency room – Frequent indicators 35 36 37

The Emergency room (ER) is the only place where victims arrive with visible signs of injuries. Potential indicators beside the typical injuries are also subtle indicators e.g. in how the victim and perpetrator do communicate.

Possible indicators – adults

- Victims of domestic violence receive radiological examinations more often, especially for physical trauma

- Unexplained or multiple injuries

- Especially head, neck, and facial injuries

- Bruises of various ages

- Injuries do not fit the history given

- Bite marks, unusual burns

- Injuries on parts of the body hidden from view (including breasts, abdomen and/or genitals), especially if pregnant

- Chapped lips

- Teeth knocked out

- Uncomfortable/unusual atmosphere, fear, hierarchy

- The accompanying persons answers all questions

- The history about the injury does not fit to the injuries

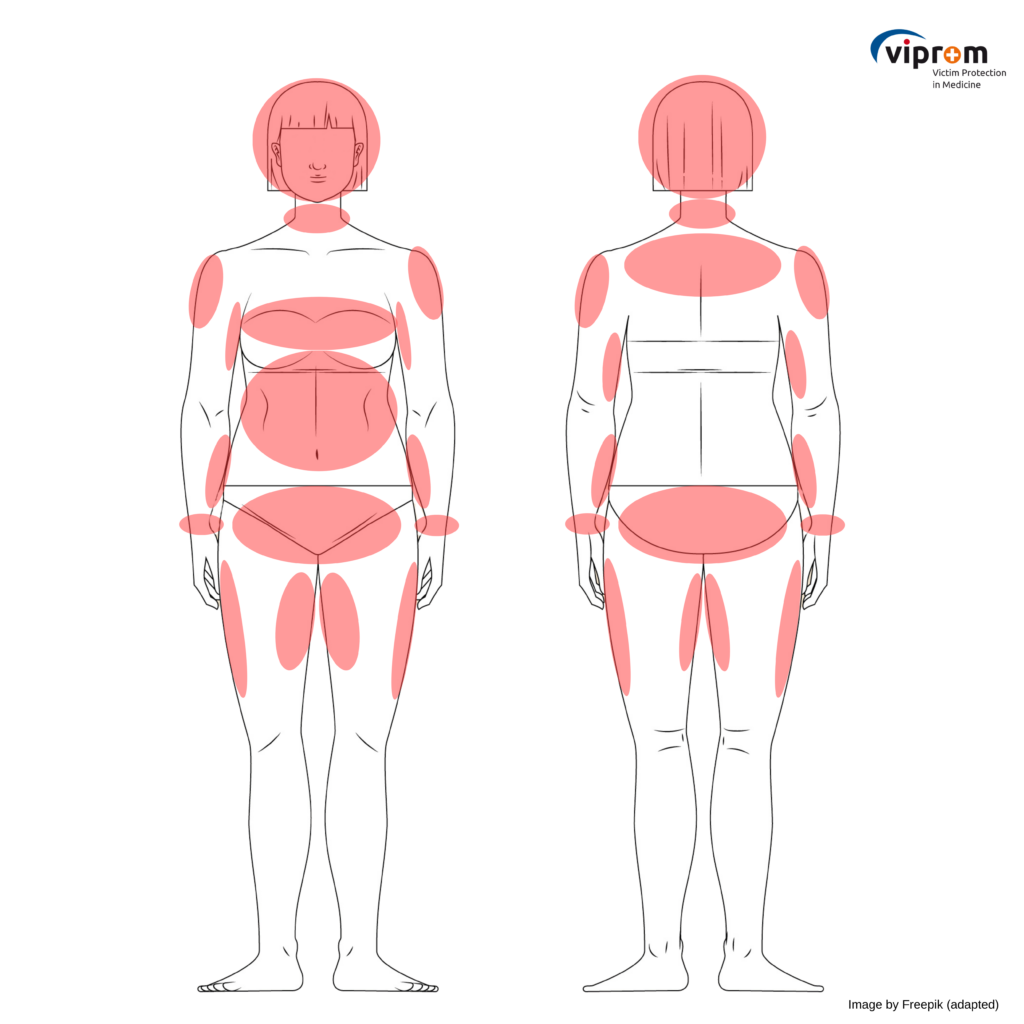

There are potential differences in locations of injuries related domestic violence between male and female victims. For example, females are more often punched in the abdomen in particular when they are pregnant or they present with injuries in the lower part of the breast. Regions frequently injured -depending on sex – are marked in the illustrations in the female or male body below.

Male body

Female body

Image by Freepik (male) and Freepik (female): adapted

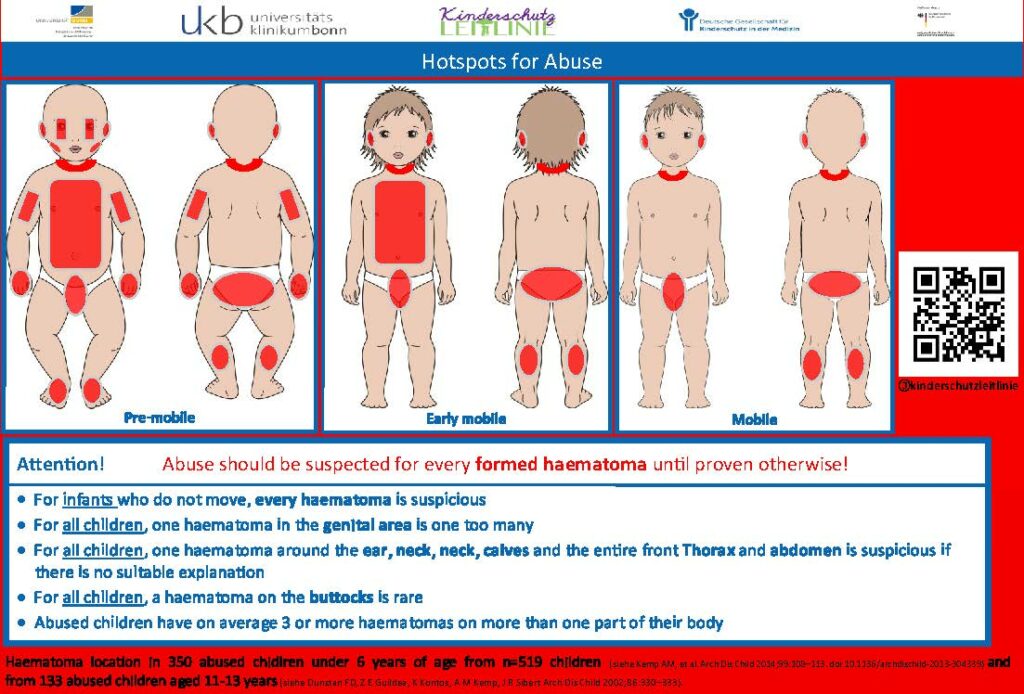

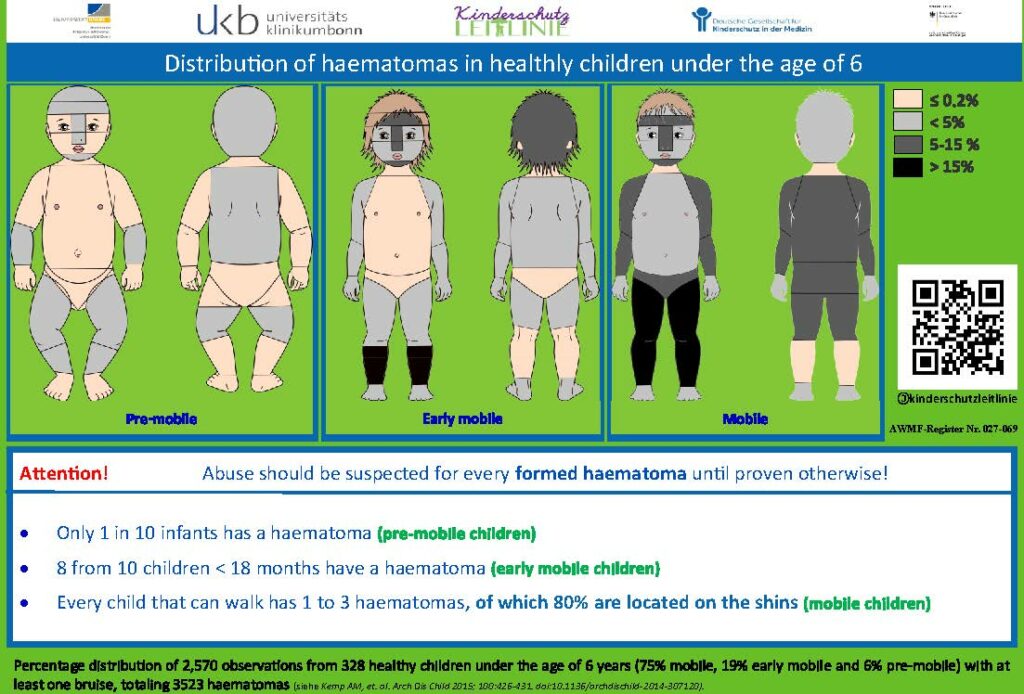

Possible indicators/injuries – children

- Described history is not consistent with injuries.

- Unusual injuries, e.g.

- Severe injuries of any kind

- Frequent fractures

- Very pronounced injuries of any kind

- Unusual appearance (e.g., patterned injuries, such as bite marks)

- Unusual (“protected”) localisation of injuries (including lips, teeth, oral cavity, eyelids, earlobes, buttocks, genitals, fingertips, etc.)

- Untreated (old) injuries

- Unexplained injuries in non-mobile children

- Injury “inappropriate” for the child’s age; healthy /infants do not have bruises. Even small, medically irrelevant bruises indicate inappropriate handling of the child

Caution: Severe internal injuries (e.g., fractures) may lack external injuries! Shaking an infant is life-threatening – and also not externally visible.

Possible indicators for domestic violence against the elderly

- Contusions affecting the inner arms, inner thighs, palms, soles, scalp, ear (pinna), mastoid area, buttocks

- Multiple and clustered contusions

- Abrasions to the axillary area (from restraints) or the wrist and ankles (from ligatures)

- Nasal bridge and temple injury (from being struck while wearing eyeglasses)

- Periorbital ecchymoses

- Oral injury

- Unusual alopecia pattern

- Untreated pressure injuries or ulcers in non-lumbosacral areas

- Untreated fractures

- Fractures not involving the hip, humerus, or vertebra

- Injuries in various stages of evolution

- Injuries to the eyes or nose

- Contact burns and scalds

- Scalp haemorrhage or hematoma

Case Study: Elderly abuse

A patient on my list for over 10 years, aged 87 years, lived after her daughter’s death with her son-in-law in a detached family house. The patient was suffering from cardiac insufficiency and repeatedly she came with injuries and excoriations on her legs to my private practice. “She is always running down the stairs too quickly!” said the son-in-law who accompanied her. His behaviour was then rather uncooperative and “strange”. The patient insisted that she was kindly well nursed by him and a niece with a nurse living nearby looked after her.”

Task of reflection

(1) Consider the indicators presented in the case study for conspicuous and/or concerning behaviours of the son-in-law. What might these indicate and how might they relate to elder abuse or neglect?

(2) Consider the patient’s perspective as she insists that she is kindly nursed by her son-in-law and cared for by a niece. How might this influence your view of things and what might help you to better assess the patient’s true feelings and needs?

Case from The Medical Women’s International Association’s Interactive Violence Manual

For further reflection: At the surgical emergency department

Setting

Julia has been experiencing severe abdominal pain and visits the emergency department of a hospital. David, her partner, accompanies her. Julia and David enter the examination room of the emergency department. Dr. Anderson, the physician, greets them and instructs Julia to take a seat. When the physician asks some questions, responds David or interrupts Julia when she starts to respond.

Task

(1) Please read the description of the setting ting of the image above and look at the image itself: What “red flags” can you identify which may point towards DV?

Excursus: Radiological findings

The following description refers to domestic violence against adults in particular (e.g., partners). A special aspect in the broader context is child abuse – radiological findings may be decisive for its detection.

Examples for radiologic findings that may point towards DV can be found in this source: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/intimate-partner-violence?lang=us

Common injuries detectable with medical imaging

- Injuries to the reproductive organs (also during pregnancy, e.g., chorionic hematoma)

- Acute fractures (especially in the facial region, e.g., nasal bone fracture, orbital floor fracture; but also fractures of the extremities)

- Subacute and temporally indeterminate fractures (especially face, extremities, and spine)

- Soft tissue injuries (e.g., hematoma and laceration)

Evaluation of image findings and the role of radiology

- Radiological findings and imaging data contribute to the documentation of the extent of physical injuries.

- However, the injury patterns of adult victims of domestic violence are similar to those of other causes of injury.

- The positive predictive value of a radiological examination alone for the possible presence of domestic violence is limited but can be better assessed and thus increased by considering the overall clinical context.

- This can include injury patterns that do not match the medical history, the presentation of multiple injuries of different ages and frequent radiological examinations in the past.

- The radiologist’s complementary view of the case and the often somewhat calmer situation when preparing and reporting the findings of the examinations (compared to the emergency room) can thus facilitate the detection of domestic violence.

8. Paediatrics – Frequent indicators

“A deliberate constant change of paediatricians is a possible indicator of DV and can lead to vulnerable and affected children and adolescents being recognised too late” 38

Here, you will find a range of possible indicators in children. 39

Possible indicators of domestic violence

- Slow weight gain (in infants)

- Noticeable examination findings or other indications of neglect

- Lack of or inadequate medical care for illnesses

- Poor care condition of the child

- Poor nutritional state of the child or extreme obesity

- Inappropriate clothing e.g. wearing long-sleeved clothing and trousers in hot weather

- Difficulty eating/sleeping

- Physical complaints

- Eating disorders (including problems of breast feeding)

Possible psychological indicators

- Aggressive behaviour and language, constant fighting with peers

- Passivity, submission

- Appearing nervous and withdrawn

- Difficulty adjusting to change

- Regressive behaviour in toddlers

- Speech development disorders

- Psychosomatic illness

- Restlessness and problems with concentration

- Dependent, sad, or secretive behaviour

- Bedwetting

- ‘Acting out’, for example animal abuse 40

- Noticeable decline in school performance

- Unexplained absences from school

- Overprotective or afraid to leave mother or father

- Stealing and social isolation

- Exhibiting sexually abusive behaviour

- Feelings of worthlessness

- Transience

- Lack of personal boundaries

- Depression, anxiety, and/or suicide attempts

Possible injuries

- Described history is not consistent with injuries.

- Unusual injuries, e.g.

- Severe injuries of any kind

- Frequent fractures

- Unusual appearance (e.g., patterned injuries, such as bite marks)

- Unusual (“protected”) localisation of injuries (including lips, teeth, oral cavity, eyelids, earlobes, buttocks, genitals, fingertips, etc.)

- Untreated (old) injuries

- Unexplained injuries in non-mobile children

- Injury “unusual” for the child’s age; healthy /infants do not have bruises. Even small, medically irrelevant bruises indicate inappropriate handling of the child

- Injuries due to forced or careless feeding

- Contusions (tissue bruising) of the lips or gingiva (due to extreme feeding)

- Burns because the food was too hot

- Forced feeding with bottle: upper incisors intruded lingually, gums show round tear from plastic ring on rubber teat

Caution: Severe internal injuries (e.g., fractures) may lack external injuries! Shaking an infant is life-threatening – and also not externally visible.

Source: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderschutz in der Medizin (Kitteltaschen https://dgkim.de/?page_id=243)

Possible indications regarding the caregivers or parental behaviour 41

- Psychological abnormalities/illnesses in the parents/mother/father

- Signs of parental issues (e.g., aggression, potential for violence, delinquency, lack of education, marital conflicts)

- Families experiencing psychosocial stressors (e.g., poverty, unemployment, early and/or single parenthood, linguistic isolation, multiple births, child developmental delays)

- Substance use (regardless of the substance) and other addictions in parents (e.g., gambling, sexual, and shopping addiction)

- Inability of parents to correctly interpret and respond to signals from a /infant/child; inability to meet the needs of the new-born/infant/child; lack of attachment to the new-born /infant/child

- Lack of cooperation/therapy compliance on the part of parents e.g.:

- Failure to follow recommendations of the medical personal, inadequate care of chronically ill children by parents

- Failure to administer (regular) medication to the child, skipping the child’s check-up appointments

- Failure to attend (follow-up) appointments after illness/injury, frequent unexcused absences from treatment appointments; conspicuously frequent cancellations of treatment appointments

| Red flags that should make you alert:42 • Noticeable hematomas are a concern in non-mobile infants. • In any child, having a hematoma in the genital area is concerning. • In any child, having hematomas in multiple regions such as the area of the ear, neck, nape of the neck, calves, and the entire front of the thorax and abdomen is excessive and suspicious if there is no appropriate medical history available. • In any child, having a hematoma in the buttocks area is very rare. Abused children typically have three or more hematomas in multiple regions. |

Case Study: Children at serious risk in domestic violence households

This case is about Daniel, a 4-year-old boy, and his mother Ms. Luscak, aged 27 years who had four different partners. She misuses alcohol and depicts occasional violence towards her partners. She speaks little English. Daniel had 2 siblings, a 7-year-old sister Anna by mum’s first partner and a 1-year-old brother Adam by mum’s fourth partner, Mr. A. On 27 different occasions, the police were called to domestic violence incidents often complicated by both parents being drunk. On 2 occasions Daniel’s mum took sleeping pill overdoses with the intention of committing suicide. The family moved house on numerous occasions due to an inability to pay rent. When pregnant with Adam, Mr. A. urged Ms. Luscak to have a termination. She missed 4 antenatal appointments. At one stage she was hospitalised and Mr. A took the drip out of her arm and she self-discharged.

Daniel had a spiral fracture to the left arm reported as due to jumping off the settee with his sister the previous when being seen at the emergency room. Bruises on his shoulder and lower tummy were explained by his mother to be due to falling off his bike regularly. Meetings of health care professionals took place but the long history of domestic violence was not considered. When Daniel started school, there were frequent absences as for his sister Anna. Teachers became concerned as Daniel was getting markedly thinner and always seemed hungry, taking food from lunchboxes of other children. Daniel had poor English and was a shy and reserved boy and did not talk to the teachers.

Task of reflection

(1) Reflect on the numerous signs and red flags presented in Daniel’s case. What were the early indicators of potential abuse, and how might they have been identified sooner?

(2) What were the missed opportunities for intervention and support of healthcare professionals? How could it have been done better?

Case adapted from The Medical Women’s International Association’s Interactive Violence Manual

Spotlight on Dentistry: Identification of victims of domestic violence

9. Dentistry – Frequent indicators

“Dentists are in the unique position to be the first line of defence in identifying evidence of assault, and then reporting potential cases of domestic violence”. 43

Dentists are important first responders in identifying domestic violence

“My Dentist picked up on my problems as I was emotional on a visit last year. He handled it delicately (as did his nurse) he also handed me printed out information on police, victim support, domestic abuse agencies. Even though I denied I needed them (at that time), I did go on to explore more and use them. He saved me!” 44

“I was unaware of the physical toll the violence had had on me until a couple of years

ago after needing a panoramic x-ray of my face for some dental surgery. After I left the dentist and was driving home the surgeon contacted me to ask if I had ever been in a serious car accident. When I said no, she explained that I had numerous calcified and misaligned healed fractures in my face. The effect of being told this was extraordinary for me. I sat in my car on the side of the road and wept. It seems ludicrous now, in hindsight, to have been so shocked and so deeply saddened by this information, and yet it was as though someone had handed me a certificate that said ‘you really were horribly abused and we can actually see that’ and for the first time no one was blaming me for it.” 45

Task for reflection

(1) Please read the two quotes. Why do you think dentists are important first responders in identifying domestic violence?

“I think being a dental practice owner we’re in an ideal position [to ask about DV], especially when we get to know our patients as well, we can. We’ll be able to respond to changes in behaviour and I think it’s [screening for and identifying DVA] of vital importance.” 46

Why are dentists well placed to identify victims of DV?

They spend an average of 30-60 minutes with their patients compared to an average of 7-10 minutes for primary care physicians. 47

Dentists are able to know patients better due to routine check-ups or therapies with several treatment sessions. They see patients in this case several times within 12 months and may be thus able to detect changes in behaviour and can approach the patient accordingly. 48

Many victims of domestic violence cancelled their physician appointments if they had injuries to the head, neck or face, but tended to keep their dental appointments. 49

Various studies report that injuries to the head, neck and face area occur in 40-75% of cases, as this area is unprotected and therefore easy to reach. Those visible injuries may demonstrate the superiority of the perpetrator. A woman who has to be treated for a facial injury has a one in three chance of being a victim of domestic violence. 50 51

Image (clock) by Vecteezy / Image (calendar) by Freepik / Image (mobilephone) of katemangostar by Freepik / Image (face) of Ambiguous Vectors by Vecteezy

The video highlights that identification of victims of domestic violence can also play an important role in the dental practice. It is important that dental professionals ask specific questions on DV, follow-up on cases they suspect DV being present and document findings and injuries which may be related to DV in a timely fashion and as such that it can be used in court later.

Possible indicators for domestic violence in dentistry

Indicators in the neck-face area 52 – Facial trauma (synonym=maxillofacial trauma)

Injuries of the head-neck-face region are considered a significant indicator of DV. Odontologists dentists, and maxillofacial surgeons should be able to recognise maxillofacial trauma in the head and neck region as a possible indicator of DV. From several studies maxillofacial trauma in women is associated with DV in 50% of cases, and the most affected area is the middle third of the face in 60% of cases.

Definition

(Maxillo)fascial trauma is damage to the soft tissues or bones of the face that can be caused by a traumatic injury such as a fall, collision or blow.

A facial trauma includes:

- Facial soft tissue injuries e.g. grazes, bruises, abrasions, cuts, scratches, haematomas, burns and lacerated contusion wounds.

- Maxillofacial fractures associated with DV may include pain, swelling, hematoma, bleeding, deformity of the face, difficulty breathing or speaking, and loss of sensation or vision.

- Traumatic bone injuries: fractures of the nose, zygomatic bone, upper and lower jaw and eye socket.

Over a period of 5 years (1992-1996), the injuries of patients hospitalised due to domestic violence injuries were documented in a hospital in Portland (USA). 53

The results can be seen in the following image. Please click on each percentage (cross in the corresponding circle) to open the corresponding information.

Facial trauma involves the following injuries (in descending order of frequency):

- by soft tissue injuries: contusion, abrasion, and laceration

- by fracture to the jaw

- by dental fracture: crown fractures are in half of the cases, followed by root fractures, subluxations and finally by intrusions

- by fracture of the cheekbone

- by nasal fracture

In those cases, maxillofacial surgeons should: 54 55 56 57

- Perform a head-and-neck examination.

- Evaluate the temporomandibular joint: if there was trauma it could be a sign of violence or abuse.

- Assess any injuries to lips, tongue, palate, frenules caused by repeated trauma from violence. If so, assess especially the different temporal location.

- Inspect skin for abrasions, bruises, healing burns, non-self-inflicted bite marks; Inspect eyes and nose (e.g., ecchymoses, hematomas, petechiae)

- Evaluate fractures that occur at the front of the skull. They are often the result of direct trauma to the forehead. Frontal bone fractures can manifest in a variety of ways: from initial pain and swelling to visible bruising, and in some cases, may even alter the shape of the forehead.

- Assess fractures of the nose, among the most common injuries when it comes to facial trauma.

- Assess fractures of the bony socket of the eye and prominent cheek bones, among are among the most delicate and complex to treat. They can affect the mobility of the eye and cause swelling and bruising.

- Evaluate a fracture of the upper jaw that can seriously affect daily function.

- Assess trauma to the rounded end of the mandible that connects to the temporal bone of the skull. Fractures of the mandible, or the lower jaw, represent one of the most challenging facial traumas to manage. In addition to impairing normal mouth function, affecting the ability to open and close the mouth properly. These fractures can manifest a range of symptoms in addition to pain, such as anaesthesia, paraesthesia, and dysesthesia. Some patients may also report hypoesthesia or hyperesthesia.

- Assess fractures of the mandibular condyle, involving the rounded parts of the mandible, those that form a joint with the temporal bone of the skull, allowing us to open and close the mouth. In addition to pain, an injury in this area can seriously impair the mobility of the mouth.

- Evaluate fractures involving both the upper jaw and mandible, which are particularly complex since they affect both the upper and lower mouth. This type of trauma can have drastic effects on normal oral function, limiting the ability to chew, speak and even breathe.

- Assess facial smashing, which indicates multiple simultaneous fractures in different areas of the face and involving most, if not all, of the facial bones. Facial smashing can lead to combined fractures, making the facial bones particularly unstable. This instability can cause movement and deformation of bone fragments, compromising the structural integrity of the skull and face.

More detailed descriptions of the injuries in each location on the face can be found when clicking on the cross in the corresponding circle.

Image by Freepik

Indicators in the mouth and tooth area

Please press click on each cross in the corresponding circle on each mouth to get specific information on indicators in the mouth and tooth area: 60 61

Image by brgfx Image on Freepik.

A table summarising all relevant indicators can be downloaded here:

Indicators for abuse of children and neglect of children

Abuse and neglect are both forms of domestic violence, but they differ from each other (see the table below). 66 67

| Form of DV | Abuse | Neglect* |

|---|---|---|

| Physical | Violent, non-accidental injuries | · Inadequate care and/or health care over a longer period of time (e.g. “dental neglect”), malnutrition, inadequate personal hygiene, inappropriate clothing · Chronic state of inadequate care |

| Emotional | Psychological damage due to excessive demands, threats, triggering of fears and feelings of inferiority (“I wish you weren’t born”) | Persistent and repeated disregard of the child’s emotional needs, deprivation of care, love and security |

| Sexual | Active and passive involvement of the child in sexual acts |

Possible indicators of physical child abuse that may be seen in the dental practice:68 69

- Frenulum tear

- Frenulum tear: bleeds very heavily (looks like even more blood to the layperson due to mixing with saliva), thus parents usually go straight to the doctor or emergency service in the event of an accident.

- If the tear has been healing for several days, the secondary healing often looks like an inflammation to the layperson. The child is often only taken to a dentist. Be attentive and ask for a plausible explanation.

- Injuries to teeth

- Teeth with fractures, dislocations, post-traumatic avitalities.

- Tooth dislocations and extrusions buccalwards: suspected maltreatment e.g. the pacifier was forcibly removed.

- Star-shaped fractures in the enamel (“it explodes”), caused by hitting with a ring on the finger without injuring the lips, very atypical for accidental trauma.

- In accidental injuries, tooth fractures usually present themselves with the prismatic lines of the enamel, tooth intrusions and luxations usually in the lingual or apical direction!

- General information

- Injuries at different stages of healing.

- Atypical localisation or pattern of injuries: bilateral lip injuries or chin haematomas only occur due to pinching.

“Neglect is the most common form of child endangerment” 70

Physical neglect: Indicators for physical neglect can be found in Module 1.

Dental neglect

Definition

The English Society of Paediatric Dentistry:

“Dental neglect is defined as the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic oral health needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s oral or general health or development” 71

- Dental neglect frequently leads to a persistent state of untreated carious lesions. There is no specific threshold value that defines dental neglect based on the number of carious lesions. However, it is established that in the permanent dentition of neglected children, untreated carious lesions occur at a frequency eight times higher than in non-neglected children.72

- If caries or dental trauma occurs, please talk to the child/adolescent and their legal guardian after ruling out a differential diagnosis and before making a suspected diagnosis of dental neglect:

- Impairment due to caries

- Duration and severity of caries

- Knowledge and awareness of oral health and hygiene

- Willingness, ability, availability to treat the caries

- If the parent/guardian is aware of the disease and the need for treatment, but refuses to provide their child with treatment and support with oral hygiene or does not keep the dentist appointment, this is an important indication of neglect. 73

Early Childhood Caries (ECC)

“Teat bottle caries” as a manifestation of child neglect: 74

- Carious milk tooth disease, which occurs after the eruption of the first milk teeth until the beginning of the change of teeth at the latest (6th year of life).

- Cause: sugary drinks given via feeding bottles combined with inadequate dental care.

3 degrees of severity according to Wyne:

Type 1: Mild to moderate

– Isolated carious lesions on milk molars and milk incisors.

Type 2: Moderate to severe

– Carious lesions on the palatal surfaces of the deciduous incisors in the upper jaw, lower teeth are caries-free.

– Depending on age, the deciduous molars are also affected.

Type 3: Severe

– Carious lesions on almost all deciduous teeth, including the lower incisors.

– Areas are affected that only rarely show caries.

Initial caries or early forms of early childhood caries on the upper milk incisors:

3A) Inactivated initial caries on the upper incisors. The whitish bands are now shiny and smooth due to remineralisation. The localisation suggests that teeth were not brushed, especially in the first year of life, but that this has now been done well for some time, i.e. the recommendations have been followed.

3B) Maxillary anterior teeth with caries, which could only be recognised after removal of massive plaque, in a 12-month-old child represent an early marker for neglect of at least oral care. This is not only due to a temporary lack of dental care, but also to a high frequency of consumption of sugary drinks via the teat bottle. Fortunately, a change in cleaning and eating habits could inactivate caries and prevent toothache and subsequent treatment.

4A) Teeth brushing appears to have improved significantly following information/instruction provided by the parents during the preliminary visits for brushing at home. Clinically, there is no evidence of a dentogenic fistula or even an abscess. The degree of inactivation of the extensive lesions suggests a significant improvement, i.e. a longer-lasting change in behaviour with regard to oral hygiene at home and diet.

4B) Here too, the degree of inactivation of the large affected carious teeth indicates a significant change in behaviour with regard to oral hygiene at home and diet. However, mature dental plaque is still partially visible and an abscess in region 54 can be diagnosed, which is associated with a previous pulp necrosis with pain and the risk of a tendency to spread towards the eye. Acute dental treatment is therefore required here, which may be carried out under anaesthetic due to the large scope of treatment for this small child.

Case study: Dental neglect

A little girl comes to your dental practice with her mother. She is about five years old. You notice that the girl, unlike most other girls her age, is very quiet and anxious. She is also much smaller and thinner. You also notice that the girl is wearing clothes that are clearly dirty. She also does poorly during your examination, and all of her existing milk teeth are severely damaged by decay. The girl tells you that some of her teeth hurt. The mother states that the teeth have actually been darkly discoloured for the whole time, i.e. for several years.

Task for reflection

(1) What could be possible causes or reasons for the child’s poor dental status?

Please click on each cross in the corresponding circle to get specific information on the different scenarios.

Case study: Early Childhood Caries

A young boy is coming to your dental practice. He presents with this dental status.

Task for reflection

(1) Please look at this photo. Please describe what you see.

(2) What is your diagnosis? What may be the reason for this poor dental status?

(3) What would you do as dentist as next steps?

Solution of task

Active carious lesions, particularly in the maxillary anterior teeth in the typical ECC (Early Childhood Caries) pattern, are evidence of chronic neglect. The purple colour of the stained plaque and the soft nature of the dentin lesions underline the activity of the caries process and require the fastest possible changes in cleaning and feeding behaviour.

Knowledge assessment:

Sources

- https://www.abuseisnotlove.com/de-de/signs ↩︎

- Sondern, Lisa & Pfleiderer, Bettina. (2021). Medical doctors are important frontline responders in domestic violence-fighting networks – but it is challenging to have them actively involved. European Law Journal. 21. p. 141 – 150. https://bulletin.cepol.europa.eu/index.php/bulletin/article/view/414/333 ↩︎

- Sondern, Lisa & Pfleiderer, Bettina. (2021). Medical doctors are important frontline responders in domestic violence-fighting networks – but it is challenging to have them actively involved. European Law Journal. 21. p. 141 – 150. https://bulletin.cepol.europa.eu/index.php/bulletin/article/view/414/333 ↩︎

- Stiles, Melissa. (2003). Witnessing domestic violence: The effect on children. American family physician. 66. 2052, 2055-6, 2058 passim. ↩︎

- Mellar, B. M., Hashemi, L., Selak, V., Gulliver, P. J., McIntosh, T. K. D., & Fanslow, J. L. (2023). Association Between Women’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Self-reported Health Outcomes in New Zealand. JAMA network open, 6(3), e231311. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1311 ↩︎

- https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-child ↩︎

- https://www.gewalt-ist-nie-ok.de/de/was-ist-zu-hause-los/welche-folgen-hat-haeusliche-gewalt-fuer-dich, 11. Dezember 2023 ↩︎

- https://www.gewalt-ist-nie-ok.de/de/was-ist-zu-hause-los/welche-folgen-hat-haeusliche-gewalt-fuer-dich, 11. Dezember 2023 ↩︎

- After: Danese A, Widom CS (2023). Associations Between Objective and Subjective Experiences of Childhood Maltreatment and the Course of Emotional Disorders in Adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry. 80, 1009-1016. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2140. ↩︎

- Lee, V.M., Hargrave, A.S., Lisha, N.E. et al (2023). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Aging-Associated Functional Impairment in a National Sample of Older Community-Dwelling Adults. J GEN INTERN MED

https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08252-x ↩︎ - Stiles, Melissa. (2003). Witnessing domestic violence: The effect on children. American family physician. 66. 2052, 2055-6, 2058 passim ↩︎

- Stiles, Melissa. (2003). Witnessing domestic violence: The effect on children. American family physician. 66. 2052, 2055-6, 2058 passim ↩︎

- Moylan CA, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ (2010). The Effects of Child Abuse and Exposure to Domestic Violence on Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems. J Fam Violence. 25(1):53-63. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9 ↩︎

- Monnat SM, Chandler RF (2015). Long Term Physical Health Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Sociol Q. 56(4):723-752. doi:10.1111/tsq.12107 ↩︎

- Vargas, L. Cataldo, J., Dickson, S. (2005). Domestic Violence and Children . In G.R. Walz & R.K. Yep (Eds.), VISTAS: Compelling Perspectives on Counseling. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association; 67-69. https://www.counseling.org/docs/disaster-and-trauma_sexual-abuse/domestic-violence-and-children.pdf?sfvrsn=2 ↩︎

- Felitti V.J. et al (1998), ‘The Relationship of Adult Health Status to Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 14, pp. 245-258 ↩︎

- https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/eiges-work-gender-based-violence/intimate-partner-violence-and-witness-intervention?lang=sl ↩︎

- Department of Health and Social Care (2017): Responding to domestic abuse: A resource for health professionals: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/597435/DometicAbuseGuidance.pdf ↩︎

- RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book ↩︎

- Women’s Legal Service NSW (2019): When she talks to you about the violence – A toolkit for GPs in NSW: https://www.wlsnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/GP-toolkit-updated-Oct2019.pdf ↩︎

- Women’s Legal Service NSW (2019): When she talks to you about the violence – A toolkit for GPs in NSW: https://www.wlsnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/GP-toolkit-updated-Oct2019.pdf ↩︎

- RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book ↩︎

- Western Australian Family and Domestic Violence Common Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework (2023),p.1, Factsheet: https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2021-10/CRARMF-Fact-Sheet-2-Indicators-of-FDV.pdf ↩︎

- RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book ↩︎

- RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book ↩︎

- RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book ↩︎

- Women’s Legal Service NSW (2019): When she talks to you about the violence – A toolkit for GPs in NSW: https://www.wlsnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/GP-toolkit-updated-Oct2019.pdf ↩︎

- Hegarty (2011): Intimate partner violence – Identification and response in general practice, Aust Fam Physician. 2011 Nov;40(11):852-6. https://www.racgp.org.au/getattachment/5c90283f-fa0d-44dc-a9b5-edd7ed7776c6/Intimate-partner-violence.aspx ↩︎

- Mamun, A., Biswas, T., Scott, J., Sly, P. D., McIntyre, H. D., Thorpe, K., Boyle, F. M., Dekker, M. N., Doi, S., Mitchell, M., McNeil, K., Kothari, A., Hardiman, L., & Callaway, L. K. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences, the risk of pregnancy complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In BMJ Open (Vol. 13, Issue 8, p. e063826). BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063826 ↩︎

- Mamun, A., Biswas, T., Scott, J., Sly, P. D., McIntyre, H. D., Thorpe, K., Boyle, F. M., Dekker, M. N., Doi, S., Mitchell, M., McNeil, K., Kothari, A., Hardiman, L., & Callaway, L. K. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences, the risk of pregnancy complications and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. In BMJ Open (Vol. 13, Issue 8, p. e063826). BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-063826 ↩︎

- Lawn RB, Koenen KC. (2022) Homicide is a leading cause of death for pregnant women in US. BMJ.;379:o2499. doi: 10.1136/bmj.o2499. PMID: 36261146. ↩︎

- https://skprevention.ca/resource-catalogue/domestic-violence/domestic-violence-and-pregnancy/ ↩︎

- Hagemann-White C & Bohne S. (2003) Versorgungsbedarf und Anforderungen an Professionelle im Gesundheitswesen im Problembereich Gewalt gegen Frauen und Mädchen. Expertise für die Enquêtekommission ‘Zukunft einer frauengerechten Gesundheitsversorgung in Nordrhein-Westfalen’. Universität Osnabrück. https://www.yumpu.com/de/document/read/5430947/versorgungsbedarf-und-anforderungen-an-professionelle-im ↩︎

- https://skprevention.ca/resource-catalogue/domestic-violence/domestic-violence-and-pregnancy/ ↩︎

- Wu V, Huff H, Bhandari M. “Pattern of Physical Injury Associated with Intimate Partner Violence in Women Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010, 11(2):71–82.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838010367503 ↩︎ - B. Gosangi et al., Imaging patterns of thoracic injuries in survivors of intimate partner violence (IPV). Emerg Radiol 2023, 30:71-84

https://radiopaedia.org/articles/intimate-partner-violence?lang=us ↩︎ - S.I.G.N.A.L. e.V. (2018). Gerichtsfeste Dokumentation und Spurensicherung nach häuslicher und sexueller Gewalt. Empfehlungen für Arztpraxen und Krankenhäuser in Berlin:

https://www.signal-intervention.de/sites/default/files/2020-04/Infothek_Empfehlungen_Doku_2018_1.pdf ↩︎ - https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/124955/Bei-Missbrauchsverdacht-Koalition-in-NRW-will-Schweigepflicht-lockern, accessed 10. October 2023 ↩︎

- Hegarty (2011): Intimate partner violence – Identification and response in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2011 Nov;40(11):852-6. ↩︎

- Mota-Rojas D, Monsalve S, Lezama-García K, Mora-Medina P, Domínguez-Oliva A, Ramírez-Necoechea R, Garcia RdCM (2022). Animal Abuse as an Indicator of Domestic Violence: One Health, One Welfare Approach. Animals. 12(8):977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12080977 ↩︎

- https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/124955/Bei-Missbrauchsverdacht-Koalition-in-NRW-will-Schweigepflicht-lockern, accessed 10. October 2023 ↩︎

- https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/124955/Bei-Missbrauchsverdacht-Koalition-in-NRW-will-Schweigepflicht-lockern, accessed 10. October 2023 ↩︎

- https://healthsciences.arizona.edu/news/releases/dentists-can-be-first-line-defense-against-domestic-violence ↩︎

- Femi-Ajao, O. (2021). Perception of women with lived experience of domestic violence and abuse on the involvement of the dental team in supporting adult patients with lived experience of domestic abuse in England: a pilot study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 18(4), S.5

https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/4/2024 ↩︎ - Royal Commission into Family Violence: Report and recommondations (2016). The role of the health system, p.24

http://rcfv.archive.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/MediaLibraries/RCFamilyViolence/Reports/RCFV_Full_Report_Interactive.pdf ↩︎ - Owner of a dental practice and senior dentist, more than 10 years of professional experience ↩︎

- Shanel-Hogan, K. A., Mouden, L. D., Muftu, G. G., & Roth, J. R. Enhancing dental professionals’ response to domestic violence. Enhancing dental professionals’ response to domestic Violence, National health resource center on domestic violence, San Francisco.

https://www.ihs.gov/doh/portal/feature/DomesticViolenceFeature_files/EnhancingDentalProfessionalsResponsetoDV.pdf. Accessed: December, 4 ↩︎ - Femi-Ajao, O. (2021). Perception of women with lived experience of domestic violence and abuse on the involvement of the dental team in supporting adult patients with lived experience of domestic abuse in England: a pilot study, 18(4), p. 6

https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/18/4/2024 ↩︎ - RCFV Full Report Interactive – The role of the health system (p. 24) – Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists, Submission 395.

http://rcfv.archive.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/MediaLibraries/RCFamilyViolence/Reports/RCFV_Full_Report_Interactive.pdf ↩︎ - Femi-Ajao, O., Doughty, J., Evans, M. A., Johnson, M., Howell, A., Robinson, P. G., Armitage, C. J., Feder, G., Coulthard, P. (2023). Dentistry responding in domestic violence and abuse (DRiDVA) feasibility study: a qualitative evaluation of the implementation experiences of dental professionals, p. 2, BMC oral health, 23(1), 475, S. 2

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12903-023-03059-y#citeas ↩︎ - Wu V, Huff H, Bhandari M. “Pattern of Physical Injury Associated with Intimate Partner Violence in Women Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010, 11(2):71–82.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838010367503 ↩︎ - Sujatha, G., Sivakumar, G., & Saraswathi, T. R. (2010). Role of a dentist in discrimination of abuse from accident. Journal of forensic dental sciences, 2(1), 2–4. https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2948.71049, p. 3

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3009545/pdf/JFDS-2-2.pdf ↩︎ - Le, B. T., Dierks, E. J., Ueeck, B. A., Homer, L. D., & Potter, B. F. (2001). Maxillofacial Injuries associated with domestic violence Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, 59(11), 1277-1283. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11688025/ ↩︎

- Halpern LR. “Orofacial injuries as markers for intimate partner violence”. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2010 May;22(2):239-46. ↩︎

- Hashemi HM, Beshkar M. “The prevalence of maxillofacial fractures due to domestic violence – a retrospective study in a hospital in Tehran, Iran. Dental Traumatology 2011; 27:385–388 ↩︎

- Wu V, Huff H, Bhandari M. “Pattern of Physical Injury Associated with Intimate Partner Violence in Women Presenting to the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis”. Trauma Violence Abuse 2010, 11(2):71–82. ↩︎

- Saddki N, Suhaimi AA, Daud R. “Maxillofacial injuries associated with intimate partner violence in women”. BMC Public Health 2010, 10:268. Monahan K, O’Leary KD. “Head injury and battered women: an initial inquiry”. Health Soc Work 1999, 24(4):269–278 ↩︎

- Grewe, H. A. Blättner, B. Befund:Gewalt. Accessed: December, 4.

https://www.befund-gewalt.de/petechien.html ↩︎ - Rothe, K., Tsokos, M., & Handrick, W. (2015). Tier-und Menschenbissverletzungen. Deutsches Ärzteblatt Int, 112(25), 433-443.

https://www.aerzteblatt.de/archiv/171000/Tier-und-Menschenbissverletzungen ↩︎ - Moore, Roisin & Newton, Jonathon. (2012). The role of the general dental practitioner (GDP) in the management of abuse of vulnerable adults. Dental update. 39. 555-6,

https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/denu.2012.39.8.555

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233736320_The_role_of_the_general_dental_practitioner_GDP_in_the_management_of_abuse_of_vulnerable_adults ↩︎ - Denham, D., & Gillespie, J. (1994). Family violence handbook for the dental community, Mental Health Division.

https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H72-21-136-1995E.pdf ↩︎ - Garbin, C. A., Guimarães e Queiroz, A. P., Rovida, T. A., & Garbin, A. J. (2012). Occurrence of traumatic dental injury in cases of domestic violence. Brazilian dental journal, 23(1), 72–76. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0103-64402012000100013,

https://www.scielo.br/j/bdj/a/XZ3YGnmhvbxCTg8Gmd8j6yr/?lang=en ↩︎ - Jailwala, M., Timmons, J. B., Gül, G., Ganda, K. (2016). Recognize the signs of domestic violence,

https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/recognize-the-signs-of-domestic-violence/, accessed 15 November 2023. ↩︎ - Minhas S, Qian Hui Lim R, Raindi D, Gokhale KM, Taylor J, Bradbury-Jones C, Bandyopadhyay S, Nirantharakumar K, Adderley NJ, Chandan JS. Exposure to domestic abuse and the subsequent risk of developing periodontal disease. Heliyon. 2022 Dec 23;8(12):e12631. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e12631. PMID: 36619466; PMCID: PMC9813698, p. 2,

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9813698/ ↩︎ - Schöfer, H. (2012). Sexuell übertragbare Infektionen der Mundhöhle. Der Hautarzt, 9(63), 710-715.

https://www.springermedizin.de/sexuell-uebertragbare-infektionen-der-mundhoehle/8026832 ↩︎ - Moore, Roisin & Newton, Jonathon. (2012). The role of the general dental practitioner (GDP) in the management of abuse of vulnerable adults. Dental update. 39. 555-6,

https://www.magonlinelibrary.com/doi/abs/10.12968/denu.2012.39.8.555

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/233736320_The_role_of_the_general_dental_practitioner_GDP_in_the_management_of_abuse_of_vulnerable_adults ↩︎ - Denham, D., & Gillespie, J. (1994). Family violence handbook for the dental community, Mental Health Division.

https://publications.gc.ca/collections/Collection/H72-21-136-1995E.pdf ↩︎ - Schaper, J. (2019). Dental Neglect bei Kindern-Probleme im zahnärztlichen Alltag und Lösungsansätze (Dissertation, Düsseldorf, Heinrich-Heine-Universität, 2019), p. 12.

https://docserv.uni-duesseldorf.de/servlets/DerivateServlet/Derivate-54796/Dental%20Neglect%20bei%20Kindern_Dissertation.pdf p. 12 ↩︎ - Auschra, R. (2014). Wie erkennt man Kindesmisshandlungen? Blick aufs Tabu. Der Freie Zahnarzt, 58(2), 36-37; https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12614-014-1895-9 ↩︎

- Institut für soziale Arbeit e.V., Deutscher Kinderschutzverband NRW e.V., Bildungsakademie BiS (2019). Kindesvernachlässigung: Erkennen-Beurteilen-Handeln. p.10

https://www.kinderschutz-in-nrw.de/fileadmin/user_upload/Materialien/Pdf-Dateien/Kindesvernachlaessigung_2019_Web.pdf ↩︎ - Harris, J. C., Balmer, R. C., & Sidebotham, P. D. (2009). British Society of Paediatric Dentistry: a policy document on dental neglect in children. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/19470009/ ↩︎ - Greene, P. E., Chisick, M. C., & Aaron, G. R. (1994). A comparison of oral health status and need for dental care between abused/neglected children and nonabused/non-neglected children. Pediatric Dentistry, 16, 41-41.https://www.aapd.org/globalassets/media/publications/archives/greene-16-01.pdf ↩︎

- Kinderschutzleitlinienbüro, A. W. M. F. (2022). S3+ Leitlinie Kindesmisshandlung,-missbrauch,-vernachlässigung unter Einbindung der Jugendhilfe und Pädagogik (Kinderschutzleitlinie), Kurzfassung 2022, AWMF-Registernummer: 027–069.

https://register.awmf.org/assets/guidelines/027-069k_S3_Kindesmisshandlung-Missbrauch-Vernachlaessigung-Kinderschutzleitlinie_2022-01.pdf p. 20 ↩︎ - Wyne, A. H. (1999). Early childhood caries: nomenclature and case definition. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 27(5), 313-315.

https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1600-0528.1999.tb02026.x?casa_token=4Taz1zJSyVoAAAAA:ykmpWYSLgRsZBFpW9mh-ljVrLV62d9xRMKqrpTawDqT1JEoqRpz2GCK5kdtI-3G_aHogKfTboEP- ↩︎