1. Basics for Medical Assessment and Documentation

2. Screening for Domestic Violence

3. Documentation of Domestic Violence

4. Excursus: Special Aspects of Documenting Sexual Violence

5. Consent and Confidentialy

6. Medical Forensic Documentation

7. Physical Assessment

8. Photography

9. Sample/Evidence Collection

10. Discharge and Follow-Up

Spotlight on Gynaecology/Obstetrics, Surgery & Paediatric

11. Gynaecology/Obstetrics

12. Emergency Room

13. Paediatrics

Spotlight on Dentistry

14. Dentistry

Target group

This module primarily offers educational materials and pedagogical tools for professionals who train healthcare professionals working with individuals affected by domestic violence (DV) in their daily practice. It is intended exclusively for professionals in this sector and not designed for individuals experiencing DV or those in their immediate social environment.

Brief overview of Module 4

Module 4 provides an overview of medical assessment and the securing of evidence, outlining how cases or suspected cases of domestic vioelnce (DV) can be documented, how medical examinations can be conducted respectfully, and what legal and ethical aspects should be considered.

The objectives trainers can address with the materials of Module 4 are as follows:

+ Strengthen trainees’ knowledge of how to document DV injuries in a way that is suitable for legal proceedings, including relevant legal considerations.

+ Support trainees in understanding the key aspects to consider following a disclosure of DV.

Please note that the learning materials are not tailored to each country and will require local adaptation.

“Medical professionals are often the first or only professionals interacting with individuals affected by domestic violence. They have special responsibility and a valuable opportunity to intervene.”

General guiding principals on how patients with confirmed or suspected violence should be treated:1

1. Treat patients with dignity, respect, and compassion and with sensitivity to age, culture, ethnicity and sexual orientation, while recognising that domestic violence is unacceptable in any relationship.

2. Ask in the anamnesis about frequent changes of health care providers (“Doctor-Hopping”), as this can be an indicator of DV.

3. Recognise that the process of leaving a violent relationship is often long and characterised by multiple cycles of break-ups and reconciliations.

4. Attempt to engage patients in long-term continuity of care within the health care system, in order to support them through the process of attaining greater safety and control in their lives.

5. Regard the safety of victims and their children as priority.

6. A victim of domestic violence should not be forced to talk about the assault if he or she does not want to. Questions should in all cases be limited to what is necessary for medical care.

In cases of serious injuries: “…the primary emphasis should be on injury treatment, with evidence collection coming after.”

Ladd M, Seda J. Sexual Assault Evidence Collection 2

1. Basics for Medical Assessment and Documentation

The following aspects need to be considered after the disclosure of domestic violence (DV):

- A medical history needs to be taken. This should follow standard medical procedures, but it should be remembered that victims who have experienced domestic violence are likely to be traumatised. Any medical reports they may have should be checked and one should avoid asking questions they have already answered.

- Every aspect of the examination should be explained. Informed consent should be obtained for every aspect.

- Inform the victim that preserving evidence can significantly contribute to the legal process if the person decides to report to the police. It is advised to verify the specific procedures applicable in the respective country.

- If victims want evidence secured, they can contact a specially trained provider, such as a violence victim outpatient clinic, who can do this if you do not feel prepared enough to secure evidence.

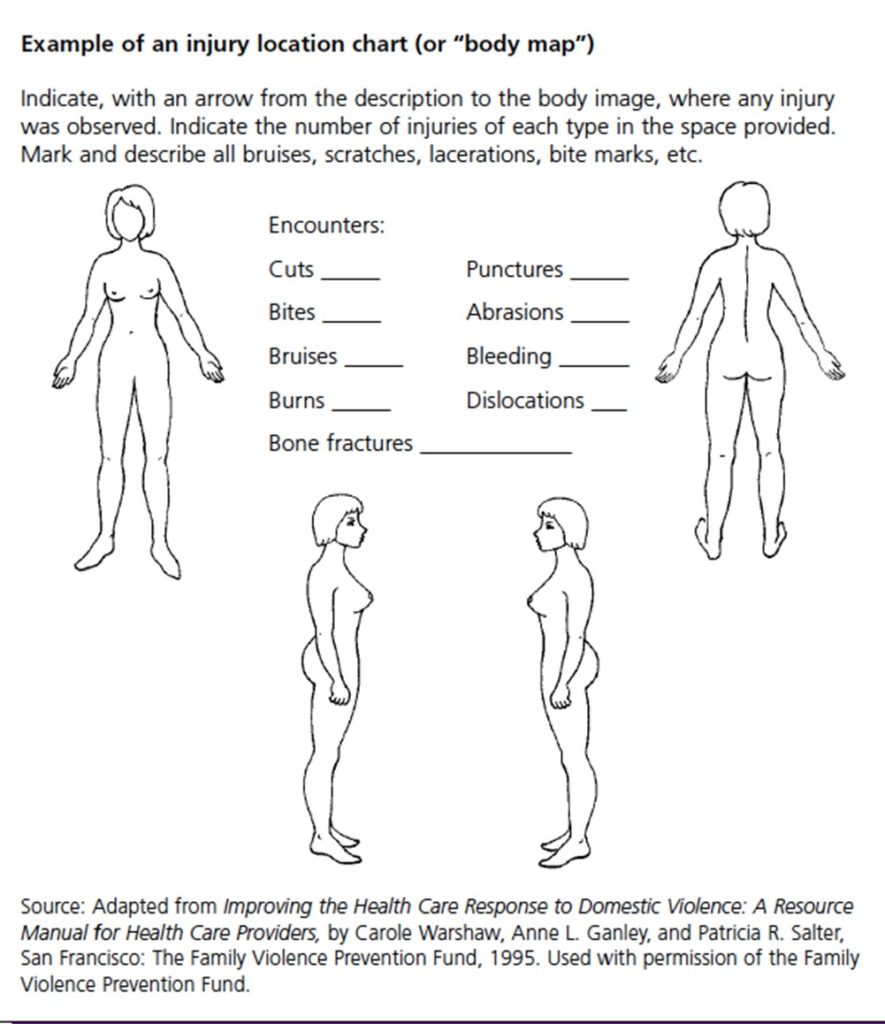

- A thorough physical examination should be carried out. Findings and observations should be recorded clearly and concisely with the help of body maps.

- The findings in the patient’s medical records are to be documented in the patient’s own words, but further questions should be also asked if necessary.

Immediately refer patients with life-threatening or severe conditions to a emergency room of a hospital.

How to perform medical assessment in a respectful way?

- Reduce power differential (sit on low stool)

- Give patient control/options – tell him/her that you will stop at any time

- Ask permission and let patient know what you are doing next

- Ask if there are any parts of the exam, such as breast or pelvic, which are particularly difficult to examine – and ask what could be done to make exam more comfortable?

- Keep explaining, encourage questions

- Ask periodically about anxiety levels

- Maintain eye contact (if culturally appropriate)

- Remind patient why you are performing exam – and explain the benefits to her/him

- Allow extra time

Mental health considerations

Many victims who are subjected to domestic violence will have emotional or mental health problems as a consequence. Once the violence, assault or situation passes, these emotional problems may get better. There are specific ways specialised health services can offer help and techniques to victims/survivors to reduce their stress and promote healing.

Some victims, however, will be more severely traumatised than others. It is important to be able to recognise these victims and to help them obtain trauma-sensitive care and communicate in a trauma-sensitive way.

- Provide a referral to a psychotherapist or local specialised counseling centers, taking into account potential challenges such as extended waiting lists.

Accompanying person

If the patient is accompanied by someone who may be the perpetrator of violence or have a close relationship with the perpetrator, do not allow them into the examination room. 3

When taking the medical history and during the examination, clinicians must ensure the patient’s ability to speak privately, either alone or with a chosen support person or victim advocate. If a patient has a personal care attendant, the patient should decide who accompanies them during the examination. The clinician should initially screen the patient alone to provide the option and avoid assumptions about safety. Caution is necessary, as family members, friends, and care attendants may pose risks, including being the source of violence or conveying information to the perpetrator. 4

Image by Freepik

Language barrier

If the patient does not speak your language or does not speak it sufficiently, ensure professional language mediation; family members are unsuitable for this task. 5

Minimise Waiting Times

Avoid waiting times, especially for victims of sexual violence and individuals reporting an assault on the neck (strangulation). 6

Of note: These are very generic procedures, which can vary from country to country. For country specific information please click on the following links:

Sweden (in Swedish, coming soon), Greece (in Italian, coming soon), Italy (in Italy, coming soon), Austria (in German, coming soon) and Germany.

2. Screening for Domestic Violence7

Conducting in-person screening for domestic violence proves effective, especially when utilising a valid and reliable screening tool in a private, one-on-one environment.

Incorporating DV screening as a routine element of patient encounters enables clinicians to address DV within the healthcare context and underscore its prevalence across diverse patient populations.

You could say:

Find more information on communication in Module 3. In Module 2, you will find both general indicators and specific indicators for gynaecology/obstetrics, surgery (emergency room), and paediatrics.

For individuals with disabilities, screening should be broadened to encompass potential abuse by a personal care attendant, in addition to DV. Unfortunately, individuals with disabilities are frequently overlooked in DV screening. A study revealed that even though 90% of women with various disabilities had encountered violence in their lifetime (with 68% in the past year), only 15% had ever been questioned about abuse or safety by a healthcare provider. 8 It is crucial to screen patients with disabilities privately before involving a personal care attendant or intimate partner for communication or mobility assistance.

Don’t miss to screen for signs of previous violence and other health conditions!

3. Documentation of Domestic Violence

Before you commence documentation, always clarify whether a sexual assault, and thus evidence collection, is the primary focus of the documentation. Decide accordingly by selecting one of the forms. Find more information on how to document on a sexual assault.

Written Documentation

“The solicitors said there just wasn’t enough evidence on my health records. Nothing to suggest my ex was to blame for my injuries. I was so let down. I thought my doctor had written down everything I said.”

Use documentation sheet and kit for evidence recovery

Always use a documentation sheet and evidence collection kit for documenting injuries and securing evidence. This will guide you through the medical assessment and support you in a systematic approach. 9

Injuries

Describe each injury in the dimensions: localisation, shape/boundary, size, colour, type.

If possible, use a table to describe the findings. Draw each injury in a body map. This will give you an overview of the location and, if necessary, concentration of injuries on the body.

Include information on: 10

- What forms were filled out to document injuries

- What labs/x-rays have been ordered

- Which report was called in or has been filed

- Name of investigating physician and which further actions were taken

Document in a way that is understandable for laypersons

Your documentation is primarily used by non-medically trained persons such as lawyers, police, members of the judiciary system and other authorities. Document in a way that is understandable and readable for these professional groups; avoid abbreviations and medical terminology.

First document, then supply

If possible, document injuries before they receive medical care. If treatment of injuries has highest priority, check whether photographic documentation of the untreated injury (injuries) is possible. If sexual violence is involved, remember to keep material (e.g., clothing) that may contain traces of the perpetrator’s DNA. See here for further details.

- Document assessments (psychiatric, safety, child/elder abuse)

- Document any referrals (social services, hotlines, mental health, legal aid, police)

- Document materials discussed, such as safety plan

Of note, giving a psychiatric diagnosis may be used in court against patient in a custody battle – be sure and include relationship of abuse to psychiatric symptoms, and the efforts patient has made to protect and care for self and children.

Describe, do not interpret 11

Document purely descriptively! Refrain from interpreting findings, such as estimating the age of the wound or assessing whether an injury was inflicted externally.

- Use neutral language – write patient “states” rather than “alleges”

- Use the patient’s own words in quotes

- Describe the situation in detail – who, what, when, where, how (threats? weapons or objects used? witnesses?)

- Describe other incidents/pattern of abuse, threats

- Describe physical and mental health consequences

- Do not include extraneous comments patient makes

Photograph injuries

Photographs are particularly informative and can supplement written documentation. Injuries in the vaginal or anal area should only be photographed if the findings are clear.

Secure evidence

As a rule, evidence is only collected in connection with sexual violence. As far as possible, it is carried out by the specialist who also provides the medical care. For female victims, a gynaecologist, for male victims a urologist, abdominal surgeon, or trauma surgeon (or surgical service) should be available.

Follow up

- Establish a safe way to contact patient

- Make follow up appointments

Here are some examples for written documentation: 12

| Avoid legal terms or those that imply disbelief or judgment | Use terms that are objective, descriptive if helpful |

|---|---|

| Patient alleges that her boyfriend burned her with a curling iron. | Patient states that her boyfriend, Robert, grabbed her curling iron out of her hand and held it against her neck. |

| Patient denies that boyfriend burned her, claims that she burned herself. | Physical findings of a burn are of size and shape consistent with report that it was caused by a curling iron. Severity and location of the burn appear inconsistent with patient’s report that she burned herself. |

| Patient became hysterical while describing the incident. | Patient cried and was shaking uncontrollably while describing the incident. |

In summary, documentation of notes related to the experienced violence should include: 13

- Patient’s responses to screening questions and minimal, but relevant details if more information is shared;

- Your objective observations of the patient’s appearance, behaviour and demeanour;

- All recent and old injuries should be recorded and described in detail, recording any pertinent negative findings.

- Your plan of care, recommendations for medical follow-up, and efforts to provide additional resources and referrals without including details of work with advocates and safety planning.

- Consideration whether any notes should be withheld under the Preventing Harm exception, advising the patient they can also request that notes be withheld under the Privacy exception.

- Any limitations to the examination (lighting, cooperation etc.) should also be documented.

- The victim should be informed that some injuries might become more visible after some days and that, if this happens, she/he should return for examination and documentation. 14

Keep in mind: As a healthcare professional, your role doesn’t involve determining the cause of injuries, whether it’s abuse, self-defence or another cause. However, through thorough examination, accurate documentation of patient statements and clinical findings, you can create a medical record that may serve as valuable legal evidence of any violence in the future.

Never forget: “The victim’s safety is considered the highest priority”

World Health Organization (WHO), 2015 15

Essential Content of the Documentation

General data

Information on the patient, the examining person, other persons present, including interpreters, as well as information on the place and time of the examination is required.

Anamnestic information

Image by storyset on Freepik

Note down anamnestic information only to the extent that it is relevant to the injury. Information on the date, approximate time, and place of the event, on any tools used, on persons involved or present, on the patient’s condition/consciousness at the time of the examination as well as brief details on the course of events (what happened when, where, how, by whom) are essential. If you use an additional sheet besides the documentation sheet, label it like the documentation sheet: with date, time, patient data. Write down information about the event in verbatim. This makes it clear that the information comes from the injured person and not from your own interpretation. Indicate who gave the information if it was not the patient himself/herself.

Survey of findings

Follow the guidelines of the documentation sheet you use. Document both positive and negative findings. If you have not examined a body region, make a note of this, and indicate the reason – e.g., “patient refuses”. A full body examination is recommended.

Attacks against the throat

An investigation is particularly urgent in cases of suspected assault against the throat (strangulation/choking). In terms of criminal law, this may be an attempted homicide. Injuries that give an indication of this sometimes disappear quickly. Always document: stasis bleedings (petechiae) in the eyelids and conjunctiva, the oral mucosa, or the posterior ear region (relevant reduction of blood outflow); temporary unconsciousness; perceptual disturbances (so-called aura), loss of control over the excretory organs, sore throat, difficulty swallowing and globus sensation.

4. Excursus: Special Aspects of Documenting Sexual Violence

Consent to undertake the examination should be obtained from the individual or their guardian. The consent should be specific to each procedure (and particularly the genital examination), to the release of findings and specimens, and to any photography. The victim may consent to some aspects and not others and may withdraw consent. The consent should be documented by signature or fingerprint. 16

- The general appearance and functioning of the individual (demeanour, mental status, drug effects, cooperation) should be documented, as well as the identity of the examiner and the date/time/location of the examination.

- Any limitations to the examination (lighting, cooperation etc.) should also be documented.

- A comprehensive examination should be performed, directed by the history provided. The sites examined/not examined should be documented.

- All recent and old injuries should be recorded and described in detail, recording any pertinent negative findings.

- The victim should be informed that some injuries might become more visible after some days and that, if this happens, she/he should return for examination and documentation

- A note should be made of any specimens collected, photography undertaken, diagnostic tests ordered or treatment initiated.

- The individual should be given a detailed explanation of the findings and their treatment and follow-up.

Specific measures should be taken if the victim is a minor. Find more information on that in Spotlight: Paediatrics.

Police complaint

Forensic documentation and securing of evidence after sexual violence can be done with or without a police report filed by the patient. Clarify whether the patient has filed or wishes to file a complaint. Be aware of time frames for securing evidence and what is available at the time of presentation. In the case of patient-commissioned documentation or confidential securing of evidence, documents are kept and only handed over to the police on request, e.g., in the case of a later police complaint. A written release from confidentiality and consent to the release of the documents is required. Keep in mind that this can vary between countries.

Medical assessment and securing of evidence

A careful explanation should be provided to the victim. This should include the reasons for, and the extent of, the proposed examination, any procedures that might be conducted, the collection of specimens and photography. A sensitive and specific explanation of any genital or anal examination is required. 17

Wear sterile surgical gloves to avoid contamination, e.g., of DNA traces with your own DNA. Keep aqua dest. in small packages ready. Take the swabs listed in your documentation sheet for each designated examination step.

Only work with self-drying swabs. Use the information provided by the patient to decide where to take the swabs. If the patient is unable to provide any information, it is imperative that you carry out a complete trace collection (as specified in the documentation form/kit).

- Samples for the toxicological examination: in principle, it is recommended to secure a blood and urine sample to prove or exclude a recent ingestion of narcotics, drugs or alcohol. If necessary, a hair sample can be additionally secured – 4 weeks after the indicated ingestion at the earliest.

- Roofies: in cases of unexplained unconsciousness or memory lapses, consider the possibility of unknowingly administered drugs.

- Clothing: secure clothing that was worn at the time of the crime – it could contain DNA evidence of the perpetrator. Pack clothes in individual paper bags. Seal the bags and label them with the patient’s name and date for later identification.

- Genital or anogenital examination: the urinary bladder should not be emptied until after the examination. Examine the external genitals and perianal area for injuries and foreign bodies first (before introducing the speculum).

- Vaginal examination: if no vaginal penetration has taken place, a vaginal examination is not necessary. However, it should always be offered. Examine the vagina and cervix for injuries and foreign bodies.

- Examination of the male genitals: examine the penis and testicles for injuries, paying particular attention to bite injuries to the penis or bruising of the testicles.

- Anal examination: inspection of the anus is best done in the lateral position with the legs drawn. If injury to the rectum or anal opening is suspected, a proctological examination should be performed.

Medical care

Clarify whether emergency contraception is necessary/wanted. Together with the patient, weigh up the risk of HIV infection or another sexually transmitted disease and proceed according to current professional standards. If necessary, refer the patient to a facility for HIV counselling and/or HIV postexposure prophylaxis (CAVE: if indicated, HIV PEP must be started as soon as possible and within 72 hours).

Documentation

All parties involved in managing cases of sexual assault should be aware of the evidence that might be collected or require interpretation. The objectives of evidence collection can include: to prove a sexually violent act and some of its circumstances, to establish a link between the aggressor and the victim, to link facts and persons to the crime scenes, and to identify the perpetrator. 18

Key Points

Key points: 19

- The physical examination is primarily conducted to address health issues. If it is performed within 5 days of the assault, there may be value in collecting forensic specimens. All examinations should be documented.

- Penetrative sexual activity of the vagina, anus or mouth rarely produces any objective signs of injury. The hymen may not appear injured even after penetration has occurred. Hence, the absence of injury does not exclude penetration. The health practitioner cannot make any comment on whether the activity was consensual or otherwise.

- There are different purposes and processes for the collection of specimens for health (pathology) and legal (forensic) investigations. Pathology specimens are analysed to establish a diagnosis and/or monitor a condition. Forensic specimens are used to assess whether an offence has been committed and whether there is a linkage between individuals and/or locations. Pathology specimens may have a significant forensic importance, especially if a sexually transmitted infection is found.

- The forensic laboratory requires information about the specimen (time, date, patient name/ID number, nature and site of collection) and what is being looked for.

- Forensic specimens: the account of the assault will dictate whether and what specimens are collected. If in doubt, collect. Persistence of biological material is variable. It will be affected by time, activities (washing) and contamination from other sources. The maximum agreed time interval (time of assault to time of collection) for routine collection is:

- skin including bite marks – 72 hours;mouth – 12 hours;vagina – up to 5 days;anus – 48 hours;foreign material on objects (condom/clothing) – no time limit;urine (toxicology) 50 mL – up to 5 days;

- blood (toxicology) 2 × 5 mL samples – up to 48 hours in tubes containing sodium fluoride and potassium oxalate.

- Hair – cut scalp hair may be useful if there is concern of covert drug administration.

- Careful labelling, storage and chain-of-custody recording is required in all cases.

- Samples should not be placed in culture media and should be dry before being packaged.

- Clothing (especially underwear) and toxicological samples should be collected if required.

- Photographs provide a useful adjunct to injury documentation. Issues of consent, access (respecting privacy and confidentiality) and sensitivities (particularly if genital photographs are taken) need to be addressed and agreed with the victim.

- Sexual violence should be considered during an autopsy examination. Documentation and specimen collection should occur in such cases.

- If sexual assault results in a pregnancy, then consideration should be given to collection of specimens for paternity testing.

5. Consent, Confidentiality and Legal Aspects

Consent

Consent to undertake the examination should be obtained from the individual or their guardian. The consent should be specific to each procedure (and particularly the genital examination), to the release of findings and specimens, and to any photography. The victim may consent to some aspects and not others and may withdraw consent. The consent should be documented by signature or fingerprint. 20

Confidentiality 21

The confidentiality of the medical forensic examination is governed by specific privacy laws, which vary based on the patient’s age, circumstances, and the examination’s location, with potential differences between countries.

Generally, physicians have the legal duty to respect patient confidentiality. Please go to the national adaptions of the platform to get the national legal framework of the VIPROM partner countries (Germany, Austria, Italy, Greek, Sweden)

Further information

- Explain to the patient how their health information is utilised, shared, and disclosed, with clear notification of confidentiality limitations.

- Inform the patient of their rights to access, correct, amend, and supplement their health information.

- De-identify personal and sensitive health information whenever feasible.

- Respect and offer communication preferences chosen by the patient.

- Ensure that privacy safeguards and consents align with the data, specifying limitations if health data is shared with providers with different privacy settings.

- Providers retain discretion to withhold information if disclosure might harm the patient, based on provider determination and ad hoc considerations.

- Refer to national legal aspects available on national platforms (e.g., Germany).

Of note: These are very generic procedures, which can vary from country to country. For country specific information please click on the following links:

Sweden (in Swedish, coming soon), Greece (in Italian, coming soon), Italy (in Italy, coming soon), Austria (coming soon) and Germany (in German).

6. Medical Forensic Documentation

The Clinical Forensic Examination

“When a patient presents for a medical forensic examination, the entire encounter is both medical and forensic. No separation exists. Even if a patient has no samples/evidence collected, they still undergo a medical forensic examination; forensic simply references the examination’s potential to be used in the legal arena. Forensic is, in this context, the intersection of healthcare and the law.” 22

A comprehensive examination and forensic documentation of physical injuries as well as securing any traces of sexual violence are an essential part of primary care.

- Forensic documentation goes beyond regular medical documentation. It is of great importance for the criminal prosecution of the offence(s) and can significantly support victims, for example, in clarifying questions of access and custody or in questions of residence law.

- Medical documentation of findings is often the only proof that victims have experienced physical domestic violence, in particular for victims who want to report the crime at a later point in time.

- Careful documentation is also important for physicians examining the victim, as it provides a valuable basis for any testimony that may be given later.

- Documentation that can be used in court needs to be confidential.

“A professional forensic documentation is the key evidence for the court proceeding […]”

7. Physical Assessment

Patients experiencing DV need a thorough evaluation considering the history of the acute assault and other relevant concerns affecting their health. For instance, limited access to medication due to violence requires clinicians to assess physical and radiological exams for indicators of previous violence or untreated health conditions. 23

Comprehensive assessment should include: 24

- “Physical assessment as dictated by the patient’s presenting complaint

- Patient’s general appearance, behaviour, cognition, and mental status

- Evaluation of body surfaces and oral cavity for physical findings

- Additional testing, including laboratory specimens and imaging

- Assessment of violence (acute and long-term)

- Specialty assessments depending on the history (e.g., strangulation assessment)

- Review of how the patient perceives the violence has impacted their health

- Damage to auxiliary aids such as wheelchairs

- Present safety concerns and needs

- Safety of children/abuse of children/child witnessing (when applicable) or other vulnerable household members

- Dangerousness, lethality, and/or risk assessment, depending on the type of tool used”

Strangulation

Strangulation refers to the blockage of blood vessels and/or airflow in the neck due to external compression, leading to asphyxia. It is a prevalent method of injury in cases of domestic violence. As a result, it is crucial for clinicians to be proficient in conducting a comprehensive assessment of patients who have experienced strangulation assaults.25

Related terms

The document titled “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations,” issued by the U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women in May 2023, provides definitions for terms related to strangulation. According to the protocol, these definitions are outlined on page 86.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf

Physical assessment: 26

- Is the patient pregnant?

- Is there an abnormal carotid pulse?

- Are petechiae present? (Note: in some types of asphyxia, such as suffocation, petechiae may appear beyond the head and neck.)

- Facial / Ears (including ear canals) / Nasal passages / Eyes / Conjunctiva / Oral / Scalp / Other (describe)

- What is the patient’s neck measurement?

- Is tongue injury present?

- Is oral cavity injury present?

- Is subconjunctival haemorrhage present?

- Is an absence of normal crepitus felt during manipulation of cricoid cartilage?

- Is there visible injury?

- Are there cranial nerve deficits?

Click here to find information on the national procedure in Sweden (coming soon).

8. Photography 27

Photography is a useful tool for medical documentation of injury as well as memorialising damage to a patient’s clothing or other belongings (e.g., assistive devices or mobility aids). However, should a patient decline photographs to be taken or an organisation does not have camera equipment available, the clinician can still perform a comprehensive medical forensic examination, relying on narrative documentation and body diagrams. Medical forensic examinations are more than a photographic catalogue of injury.

For some patients, photography may be traumatic. Before undertaking photography during a medical forensic examination, it is essential to engage in a comprehensive consent process that includes discussing the specifics of photography, such as the equipment used, storage, sharing, and access to images. The patient’s consent or assent should be reaffirmed immediately before taking photos, with the option for the patient to decline photography at any point during the examination.

Key points: 28

- Capture images of injuries discreetly, prioritizing confidentiality. Avoid photographing the breast(s) and genitalia unless there are evident injuries in those areas.

- Ensure that the photographs maintain anonymity, preventing direct identification of the individual.

- Implement a confidential code system enabling authorised personnel to identify the individual and record the time of photograph capture.

Photographic injury documentation

Use a digital camera with proper settings, including a scale for proportions (preferably an angle ruler). Note the date and patient’s name for each image.

Take at least two photos per injury: one overview for location and one detailed with scale and, if needed, a colour chart. Capture images at right angles to the injury, ensuring the scale is held directly to it. Use a neutral background and good indirect lighting.

Review the display for clarity and completeness; take additional photos if uncertain. Safely store all photos (case-related memory card, password-protected folder), then delete from the camera or reformat the SD card.

Only photograph sensitive body regions if clear findings exist, avoiding complete images of genitals. Share printed photos discreetly in an envelope.

Click here to find information on the national procedure in Sweden (coming soon).

9. Sample/Evidence Collection

Considerations for managing samples/evidence: 29

- The clinician should retain control over any samples/evidence throughout the drying process and until it is properly packaged, sealed, and handed over to law enforcement.

- Documentation should illustrate the transfer of samples/evidence from the clinician to law enforcement, establishing the chain of custody. This ensures the integrity of handling and transfer, especially for potential legal purposes.

- Healthcare providers unfamiliar with routine sample collection or lacking chain of custody forms can obtain the appropriate form from the responding law enforcement agency. A copy should be made after all samples/evidence have been transferred, kept with the patient’s medical record.

- If a patient’s adaptive or assistive equipment is damaged during the assault, document this and, if possible, take photographs. If the equipment has been repaired or replaced, document the damage in the medical forensic record.

- In cases of strangulation leading to loss of bladder/bowel control, with the patient’s permission, collect underwear and/or the next layer of clothing. These items should be individually packaged in paper bags, and if not completely dried, notify law enforcement upon transfer that additional drying time is needed.

- Sample/evidence collection may coincide with the physical assessment, but patients can decline, and it should be emphasised that this is their right without impacting the quality of healthcare services they receive.

Flowchart for Sample/Evidence Collection:

This example diagram provides guidance on the collection of samples/evidence during the process of a medical forensic examination.

Source: “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 98, accessed 26.11.23. https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf

Click here to find information on the national procedure in Sweden (coming soon).

10. Discharge and Follow-Up

Provide the patient with a copy of the documentation sheet and photos if requested. Address security issues regarding storage (access by the perpetrator?). Point out that he/she can keep and use the copy for as long as he/she wishes.

Ask about the patient’s and, if applicable, their children’s safety and protection need. If there are indications of a possible risk, and if the patient does not want to return home, refer him or her to support facilities.

Inform the patient about psychosocial counselling services for coping with violence. Assist in making contact, schedule an appointment at a specialised counselling centre, and provide written information on managing the experience. Address potential consequences for children if involved, highlighting available support services. Follow clinic rules for child protection cases. Discuss any needed medical follow-up, offer or arrange an appointment, and provide a doctor’s note if necessary.

Source: Adapted from Recommendations for forensic documentation and securing evidence after domestic and sexual violence for medical practices and hospitals in Berlin (available in German)

Click here to find information on the national procedure in Sweden (coming soon).

Spotlight on Gynaecology/Obstetrics, Surgery & Paediatrics

11. Gynaecology/Obstetrics

While a medical or gynaecological examination following a rape/sexual assault can be emotionally challenging for most girls, teenage girls and women an exam should be done as soon as possible after the incident. Ideally, the victim should be accompanied by a trusted person. This examination is essential for identifying and treating potential injuries and preserving evidence, regardless of whether the incident is reported to the police.

If the examination also aims to collect forensic evidence, it’s crucial to provide the physician with comprehensive information about the circumstances. The physician should be made aware that the medical examination includes the preservation of forensic evidence.

More information can be found in the Excursus on special aspects of documenting sexual violence.

Click here to find information on the national procedure in Sweden (coming soon).

12. Surgery: Emergency Room

In the emergency department, screening in triage should be approached with caution due to limited privacy, and screening questions may be overheard easily.

Physical examination in cases of injuries

Careful assessment of injuries should be made and noted in the medical record:

- General condition: nutrition, hydration; emotional and psychological state of the patient

- Describe Type of injuries: scars, bruises, abrasions, excoriations, haematomas, continuous solutions, lacerated wounds, burns; broken or avulsed teeth; rupture of the tympanic membrane, usually unilateral and due to violent slap;

- Morphology of injuries according to the method used to produce them: nailing, biting, cutting, manual grip, constriction, whipping, burns/burns (e.g. from cigarettes)

- Localisation of injuries: in atypical locations for accidental reported trauma – head and face, eye, nose, mouth, back and palms of hands, nails, thorax, back genital or perianal area, ankles;

- Number of lesions: often occasional occurrence of numerous lesions or scarring of the same (sometimes the lesions are so numerous that their description is identified as ‘map lesions’);

- Chronology: detection (often occasionally) of lesions in different developmental stages (simultaneous presence of fractures and bone callus, scars and continuous bleeding or under scabs, ecchymoses and haematomas with different colour evolution);

- In case of physical abuse during pregnancy, a gynaecological obstetrical examination must be carried out to assess the state of health of the woman and the foetus

| Red flag for high risk: When women are hit on the face, mouth, head, and neck, (which may be regarded as areas representing someone’s identity), as well as on breasts, pubis and limbs, (i.e. sexual areas) this could represent a marker of future femicide. 30 |

Case study – Injuries in the Emergency Room

Robin, a 36-year-old man, arrives at the emergency department seeking medical attention for a head injury sustained under unclear circumstances. The healthcare professional conducting the examination notices not only the head injury but also multiple hematomas on Robin’s left arm and additional bruises in various stages of healing.

Robin is accompanied by his sister, a woman who assumes a controlling role during the medical exam, answering questions on his behalf and closely monitoring the interaction of Robin with the physician. Robin avoids making eye contact and is reluctant to share any information by himself.

As the healthcare professional delves into the details of the incident, it becomes apparent that the story provided by his sister does not align with the observed injuries. Robin exhibits a submissive behaviour, and there’s a palpable fear of physical contact.

Task for reflection

(1) Reflect on the challenges associated with documenting evidence collection procedures. Consider how healthcare professionals can maintain detailed and accurate documentation while respecting patient confidentiality.

(2) What are possible indicators that Robin is experiencing DV? What would be your next steps?

(3) Explore the emotional and psychological impact of evidence collection on victims of domestic violence. Reflect on ways to provide psychosocial support, ensuring the well-being of the patient throughout the process.

Click here to find information on the national procedure in Sweden (coming soon).

13. Paediatrics

Indicators for domestic violence and signs of child endangerment can be found in Module 2.

A physical examination and, in particular, anogenital examination (with a colposcope) only take place with the child’s cooperation. Coercive measures are contraindicated, except in the case when medically motivated but should exclusively occur in a clinical setting so that immediate care can be provided. Forensic measures may only be undertaken if the secure storage of the collected samples (swabs) is ensured. 31

Further steps in case of suspected physical violence against children in the practice: 32

- Involve another person (medical assistant) and document their name in the patient record.

- Precise documentation of the medical history, quoting statements verbatim.

- Contact a children’s clinic for outpatient presentation (child protection outpatient clinic) or seek advice on further steps.

- Photo documentation, if possible, in the practice (ruler + color chart + patient’s name), otherwise in the clinic (child protection group/child protection outpatient clinic), preferably on the same day

Approach in case of suspicion of sexual violence 33

- For incidents that occurred a while ago: general physical examination in the practice (including development status) and assessment of behavioural abnormalities; organise an anogenital examination with advance notice, if necessary (necessary, for example, if requested by the child or the parents).

- If not a while ago, clarification of suspected cases through a risk assessment: depending on local structures in the clinic (usually through the child protection outpatient clinic) or outpatient (e.g., child protection center).

- Sequence of exams in suspected cases of sexual violence 34

This chronological flowchart illustrates the diagnostic process in cases of suspected sexual violence.

Source: AWMF (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften). (2021). AWMF S3(+) Child abuse and neglect guideline: involving Youth Welfare and Education Services (Child Protection Guideline). Retrieved from https://dgkim.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2021_11_10_langfassung_final_englisch_kkg_update.pdf

Spotlight on Dentistry

14. Dentistry

Medical assessment:35

Dental appointments can be particularly challenging for patients who have experienced or are currently facing domestic violence. The setting may evoke stress and distress, leading to a perceived loss of control and heightened anxiety. Some patients may even confront memories of domestic violence, leading to re-traumatisation.

> Patients may freeze or flinch during the examination.

> The dentist should try to make the treatment as pleasant as possible. For example, by explaining the procedure in detail and which instruments are used when and how.

Securing evidence 36 37

Court-proof documentation is always allowed! However, if this goes beyond the dental documentation, this may only be done with the patient’s consent (e.g. photographic documentation!)

- The evidence can be saved and stored in case the patient decides to go to the police later.

- If the patient does not consent to further documentation, all dental findings must still be documented in the medical file. The suspicion of domestic violence may also be recorded internally in the medical file.

How to proceed? 38

Inform the patient about the possibility of forensic documentation and obtain the patient’s consent:

The following scheme illustrates how to proceed in case the presence of domestic violence is suspected:

“Adapted from the model provided by the Dental Association (Zahnärztekammer): https://www.bzaek.de/fileadmin/PDFs/za/Praev/H%C3%A4usliche_Gewalt/Ablaufdiagramm_Zahnarztpraxis.pdf“

Case study – Victim of domestic violence in the dental practice with pain in her jaw

Mrs. Miller, from the case study in Module 3, had several haematomas on her neck (left picture below) combined with periorbital petechiae. In addition, a mandibular fracture was diagnosed in the X-ray (right picture below).

Mrs. Miller consents to forensic documentation and also photographic documentation to preserve the evidence for a later date.

She also tells you that she has not worked for seven years, since she met her husband. “Martin told me back than that I would be better able to look after our house and that he would take good care of me anyway.” For a long time, she didn’t even realise the dependency this had created. “About a year ago, when he saw me talking to the neighbour, he got very angry. Martin doesn’t like it when I talk to other people. He says he prefers to have me to himself. For a long time, I believed that he behaved like this because he loved me so much. The other day he pushed me over so that I fell with my lower jaw on the concrete floor in the garage.”

Task for reflection

(1) Describe the findings as Mrs. Miller’s dentist in the medical record using the information provided in this case study and the further information provided in chapters “Documentation in cases of domestic violence” and how to proceed in dentistry.

Case study – Documentation of DV in dentistry

In your long-standing patient Amir Rossi, who has not been at your dental practice for two years, you find the following dental status picture:

- The incisal edge of tooth 11 has broken off, making the tooth 4 mm shorter than tooth 21.

- A haematoma on the left orbital rim (monocle haematoma), which is already yellow-brown in colour.

- Large carious lesions mesially on tooth 36 and occlusally on tooth 27, which need to be treated.

As you suspect the presence of DV you ask your patient in a calm atmosphere privately about DV (more information on Communication) and learn that your patient has been suffering from his husband’s recurring aggression for some time.

Mr. Amir tells you that his husband Carl was in a bad mood about fourteen days ago in the evening because he lost an important customer at work. “If he is like this he doesn´t know what to do with his anger and if I make one tiny little mistake he gets very angry with me. Fourteen days ago, he didn´t like my cooking and he hit me in the face with his fist. Then he slipped and hit my jaw. He apologised immediately afterwards and said several times how sorry he felt.” He also tells you that his husband’s outbursts of anger happen often.

You then tell Amir that his husband has no right to hurt him and that this is not ok. You offer him help by providing further information about men’s refuges, help centers and anonymous hotlines. Although the patient begins to cry, he expresses his reluctance to leave his husband at the moment, believing that this recent violent outburst will be the last.

After allowing him time to compose himself, you inquire whether the patient would be comfortable with documenting the injuries in a manner that would be admissible in court, preserving the evidence in case he chooses to report the incident to the police later on. The patient consents, and you initiate photographic documentation with a scale. Given the acute pain and suspected intrusion of tooth 11, you additionally take an impression and capture a dental film to assess the periodontal gap.

Task for reflection

(1) What indicators are present to suspect DV?

(2) Describe the findings as Mr. Rosso’s dentist in the medical record using the information provided in this case study and the further information provided in chapters “Documentation in cases of domestic violence” and how to proceed in dentistry.

Sources

- Warm Springs Health and Wellness Center Domestic Violence Protocol “Guidelines for Clinical Assessment and Intervention”, accessed: 06.12.23

https://www.futureswithoutviolence.org/userfiles/file/HealthCare/ClinicalAssessment.pdf ↩︎ - Ladd M, Seda J. Sexual Assault Evidence Collection. [Updated 2023 Jan 29]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554497/ ↩︎

- S.I.G.N.A.L. e.V., “Gerichtsfeste Dokumentation und Spurensicherung nach häuslicher und sexueller Gewalt“, Empfehlungen für Arztpraxen und Krankenhäuser in Berlin, 2018, p. 5 ↩︎

- “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 71, accessed 26.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - S.I.G.N.A.L. e.V., „Gerichtsfeste Dokumentation und Spurensicherung nach häuslicher und sexueller Gewalt“, Empfehlungen für Arztpraxen und Krankenhäuser in Berlin, 2018, p. 5

https://www.signal-intervention.de/sites/default/files/2020-04/Infothek_Empfehlungen_Doku_2018_0.pdf ↩︎ - S.I.G.N.A.L. e.V., “Gerichtsfeste Dokumentation und Spurensicherung nach häuslicher und sexueller Gewalt“, Empfehlungen für Arztpraxen und Krankenhäuser in Berlin, 2018, p. 5

https://www.signal-intervention.de/sites/default/files/2020-04/Infothek_Empfehlungen_Doku_2018_0.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, accessed 3.12.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - Curry, M. A., Renker, P., Robinson-Whelen, S., Hughes, R. B., Swank, P., Oschwald, M., & Powers, L. E. (2011). Facilitators and barriers to disclosing abuse among women with disabilities. Violence and victims, 26(4), 430–444.

https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.26.4.430 ↩︎ - S.I.G.N.A.L. e.V., “Gerichtsfeste Dokumentation und Spurensicherung nach häuslicher und sexueller Gewalt“, Empfehlungen für Arztpraxen und Krankenhäuser in Berlin, 2018 ↩︎

- Stanford Medicine, Domestic Abuse “Documenting”, accessed 1.12.23

https://domesticabuse.stanford.edu/screening/documenting.html ↩︎ - Stanford Medicine, Domestic Abuse “Documenting”, accessed 22.11.23, https://domesticabuse.stanford.edu/screening/documenting.html ↩︎

- DOCUMENTING CLINICAL EVIDENCE OF ABUSE- “FIRST DO NO HARM”

BMC Domestic Violence Program, November 2020, p. 2, accessed 01.12.23.

https://www.bumc.bu.edu/gimcovid/files/2021/01/Abuse-Documentation-Guide-2020.pdf ↩︎ - DOCUMENTING CLINICAL EVIDENCE OF ABUSE- “FIRST DO NO HARM”

BMC Domestic Violence Program, November 2020, p. 2, accessed 01.12.23.

https://www.bumc.bu.edu/gimcovid/files/2021/01/Abuse-Documentation-Guide-2020.pdf ↩︎ - World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 28. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 15. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 27. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 27. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 30. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 30. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2015). Clinical guidelines for responding to intimate partner violence and sexual violence against women, p. 27. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/publications/WHO_RHR_15.24_eng.pdf ↩︎

- “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 44, accessed 22.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 65, accessed 22.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 77, accessed 20.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 77, accessed 20.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 86, accessed 20.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 86, accessed 21.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, accessed 21.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 44, accessed 22.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - “A National Protocol for Intimate Partner Violence Medical Forensic Examinations”, U.S. Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women, May 2023, p. 99, accessed 23.11.23.

https://www.safeta.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/05/IPVMFEProtocol.pdf ↩︎ - Cecchi, R., Masotti, V., Sassani, M., Sannella, A., Agugiaro, G., Ikeda, T., Pressanto, D. M., Caroppo, E., Schirripa, M. L., Mazza, M., Kondo, T., & De Lellis, P. (2023). Femicide and forensic pathology: Proposal for a shared medico-legal methodology. Legal medicine (Tokyo, Japan), 60, 102170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.legalmed.2022.102170 ↩︎

- Institut für Qualität im Gesundheitswesen Nordrhein „Notfall- und Informationskoffer: Kinderschutz in der Arztpraxis und Notaufnahme“

https://www.aekno.de/fileadmin/user_upload/aekno/downloads/2023/Kindernotfallkoffer.pdf ↩︎ - Institut für Qualität im Gesundheitswesen Nordrhein „Notfall- und Informationskoffer: Kinderschutz in der Arztpraxis und Notaufnahme“ https://www.aekno.de/fileadmin/user_upload/aekno/downloads/2023/Kindernotfallkoffer.pdf ↩︎

- Institut für Qualität im Gesundheitswesen Nordrhein „Notfall- und Informationskoffer: Kinderschutz in der Arztpraxis und Notaufnahme“ https://www.aekno.de/fileadmin/user_upload/aekno/downloads/2023/Kindernotfallkoffer.pdf ↩︎

- AWMF (Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften). (2021). AWMF S3(+) Child abuse and neglect guideline: involving Youth Welfare and Education Services (Child Protection Guideline). Retrieved from

https://dgkim.de/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/2021_11_10_langfassung_final_englisch_kkg_update.pdf ↩︎ - Jailwala, M., Brewer Timmons, J., Gül, G. & Ganda, K. (2016). Recognize the Signs Of Domestic Violence: Oral health professionals need to be aware of the symptoms of domestic violence and how to assist victims. Decisions in Dentistry. https://decisionsindentistry.com/article/recognize-the-signs-of-domestic-violence/ ↩︎

- Bundeszahnärztekammer. (2024). Häusliche Gewalt: Umgang mit Opfern häuslicher Gewalt in der zahnärztlichen Praxis. https://www.bzaek.de/recht/haeusliche-gewalt.html ↩︎

- Graß, H. L., Gahr, B. & Ritz-Timme, S. (2016). Umgang mit Opfern von häuslicher Gewalt in der ärztlichen Praxis. Anregungen für den Praxisalltag [Dealing with victims of domestic violence. Suggestions for daily practice]. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 59(1), 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-015-2269-4 ↩︎

- Ärztekammer des Saarlands. (2016). Häusliche Gewalt, Erkennen Behandeln Dokumentieren: Eine Information für Ärztinnen und Ärzte, Zahnärztinnen und Zahnärzte. Ministerium der Justiz, Saarland. https://www.aerztekammer-saarland.de/files/157BE0C16DE/Haeusliche_Gewalt_erkennen_behandeln_dokumentieren_2016.pdf ↩︎