1. Signs of unhealthy relationships

2. Impact of domestic violence

3. Excursus: Outsiders as witnesses of domestic violence

4. General domestic violence indicators in adults

5. Frequent indicators in children

Spotlight on the school sector: Identification of victims of domestic violence

6. Frequent indicators in the school sector

Sources

Introduction to the topic

Welcome to Module 2 on “Indicators of domestic violence”. In this module you will dive into the wide-ranging health consequences of domestic violence, learn about its identification by gaining knowledge about indicators encompassing behavioural, physical, and emotional aspects. Moreover, the role of and impact on those witnessing domestic violence will be also presented in an excursus.

Learning objectives

+ Understand the multifaceted consequences of domestic violence on victims, families, and communities, including physical, psychological, and social impacts.

+ Acquire the skills to identify potential indicators and “red flags” – using behavioural, physical, and emotional cues.

+ Recognise the emotional and psychological effects of witnessing domestic violence, particularly on children, and understand the importance of creating safe environments for all family members.

1. Signs of unhealthy relationships

Some relationships can have a negative impact on our overall well-being rather than improving it. Some may even reach a level of toxicity, and it’s crucial to be able to identify warning signs.

These warning signs, often referred to as “red flags”, serve as indicators of unhealthy or manipulative behaviour. They are not always recognisable at first — which is part of what makes them so dangerous.

Toxicity can be present in all forms of close relationships e.g. between friends, at work with colleagues, between family members, or in romantic partnerships.

2. Impact of domestic violence

“Experiencing violence or abuse by an intimate partner increases the risk of developing a mental health disorder by almost three times and the risk of developing a chronic physical illness by almost twice.”

Mellar BM, Hashemi L, Selak V, Gulliver PJ, McIntosh TK, Fanslow JL (2023) (1)

Every victim is different and the individual and cumulative impact of each act of violence depends on many complex factors. While each individual will experience domestic violence uniquely, there are many common consequences of living in an environment with violence and/or living in fear. Often the short and long-term physical, emotional, psychological, financial and other effects on individuals are quite similar.

It is important to understand the effects of domestic violence on victims, because those effects are responsible for many indictors they present to us.

Please note that all the following lists are not exhaustive; it represents only a selection.

Impact of domestic violence on a child (witnessing or experiencing)

“Some of the biggest victims of

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF)

domestic violence are the smallest.”

“The way childhood abuse and/or neglect is remembered and processed has a greater impact on later mental health than the experience itself.”

Danese A., Widom CS. (2023) (2)

“People who have experienced challenging or traumatic experiences in their childhood are more likely to exhibit both physical and cognitive impairments in old age.”(7) In the following table you will find more examples of short-term and long-term impact of domestic violence on a child experience or witnessing domestic violence:

- Children who have experienced violence and have mental health problems (e.g. psychosomatic symptoms, depression, or suicidal tendencies), are at greater risk for substance abuse, juvenile pregnancy and criminal behaviour. (8)

- Children may learn that it is acceptable to exert control or relieve stress by using violence, or that violence appears to be linked to expressions of intimacy and affection. This can have a strong negative impact on children in social situations and in relationships throughout childhood and in later life.

- Children may also have to cope with temporary homelessness, change of physical location and schools, loss of friends, pets, and personal belongings, continued harassment by the perpetrator and the stress of making new relationships.

3. Excursus: Outsiders as witnesses of domestic violence

Given the short- and long-lasting negative impact on individuals living in an environment with DV and given that most never tell anyone, it is important that caregivers and family members, as well as neighbours or work colleagues which are potential witnesses of domestic violence don´t look away.

“What would you do?”

Tasks for reflection

(1) What are the “red flags” presented in this video that indicate that this is a toxic relationship where DV is present and someone needs help?

(2) What would you do?

The victim’s cooperation and consent are the most important prerequisites for intervening as a witness. An intervention by a witness can include talking to the victim, helping to access help services, or e.g. supporting the reporting of DV to the police.

Factors that may inhibit or encourage intervention by witnesses:

More information on the decisive factors for witness intervention in domestic violence can be found here: https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/eiges-work-gender-based-violence/intimate-partner-violence-and-witness-intervention?lang=sl

4. General domestic violence indicators in adults

There is a whole range of indicators to serve as “red flags” that a person may be experiencing domestic violence. Some of these are quite subtle. Thus, it is important that professionals remain alert to the potential signs and respond appropriately. Please note that none or all of these might be present and be indicators of other issues. Some victims also drop hints in their interactions and their behaviour may also be telling. Find detailed information to communication in Module 3.

Victims rely on professionals to listen, persist, and enquire about signs and cues. They need them to follow-up on conversations in private, record details of behaviours, feelings and injuries seen and reported, and support them in line with their organisation’s systems and local pathways.

Individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds may manifest their symptoms differently. Please remain conscious of your own perspective, biases, and stereotypes when communicating with a potential victim, as these factors can impact how you assess the symptoms. Find more information in Module 8.

Please note that none or all of these indicators might be present and be indicators of other issues, but they can serve as warning signs and a reason for increased attention and can point towards a history of DV.

Here, you will find a range of potential health indicators, psychological indicators for adults, and specific indicators pertaining to vulnerable groups.

For better clarity, the indicators are categorised by colour: Yellow: General indicators; Green: Behavioural indicators; Blue: Psychological indicators.

Possible health indicators

- Chronic conditions including headaches, pain and aches in muscles, joints and back

- Difficulty eating/sleeping

- Cardiologic symptoms without evidence of cardiac disease (heart palpitation, arterial hypertension, myocardial infarction without obstructive disease)

Possible psychological indicators

- Emotional distress, e.g., anxiety, indecisiveness, confusion, and hostility

- Self-harm or suicide attempts

- Psychosomatic complaints

- Sleeping and eating disorders (e.g. anorexia, bulimia, binge eating)

- Depression/pre-natal depression

- Social isolation/no access to transport or money

- Submissive behaviour/low self-esteem

- Fear of physical contact

- Alcohol or drug abuse

Possible behavioural indicators

- Frequent use of medical treatment in various facilities

- The constant change of doctors

- Disproportionately long-time interval between the occurrence of injury and treatment

- Faltering response when being asked about medical history

- Denial, conflicting explanations about the cause of the injury

- Overprotective behaviour of the accompanying person, controlling behaviour

- Frequent absence from work or studies

- Evasive or ashamed about injuries

- Seeming anxious in the presence of their partner or family members

- Nervous reactions to physical contact/quick and unexpected movements

- Easily startled behaviour

- Easily crying when being asked questions

- Extreme defensive reactions when asked specific questions

Possible indicators which apply specifically to the vulnerable group of the elderly:

Possible indicators of domestic violence against the elderly

- Lack of basic hygiene

- Wet diapers

- Missing medical aids like walkers, dentures

- Bedsores, pressure ulcers

- Caregiver speaks about the elder as if he/she was a burden

Some professionals worry that discussing suicide may trigger the person at risk, but in reality, addressing suicide can reduce their anxiety and foster understanding. If someone currently has thoughts or plans of self-harm or has a recent history of self-harm and is in extreme distress or agitation, do not leave them alone. Immediately refer them to a specialist or emergency healthcare facility.

5. Frequent indicators in children

“A deliberate constant change of paediatricians is a possible indicator of DV and can lead to vulnerable and affected children and adolescents being recognised too late”

www.aerzteblatt.de, 13.June 2021(1)

Here, you will find a range of possible indicators in children.(2)

Possible indicators of domestic violence

- Slow weight gain (in infants)

- Noticeable examination findings or other indications of neglect

- Lack of or inadequate medical care for illnesses

- Poor care condition of the child

- Poor nutritional state of the child or extreme obesity

- Inappropriate clothing e.g. wearing long-sleeved clothing and trousers in hot weather

- Difficulty eating/sleeping

- Physical complaints

- Eating disorders (including problems of breast feeding)

Possible psychological indicators

- Aggressive behaviour and language, constant fighting with peers

- Passivity, submission

- Appearing nervous and withdrawn

- Difficulty adjusting to change

- Regressive behaviour in toddlers

- Speech development disorders

- Psychosomatic illness

- Restlessness and problems with concentration

- Dependent, sad, or secretive behaviour

- Bedwetting

- ‘Acting out’, for example animal abuse(3)

- Noticeable decline in school performance

- Unexplained absences from school

- Overprotective or afraid to leave mother or father

- Stealing and social isolation

- Exhibiting sexually abusive behaviour

- Feelings of worthlessness

- Transience

- Lack of personal boundaries

- Depression, anxiety, and/or suicide attempts

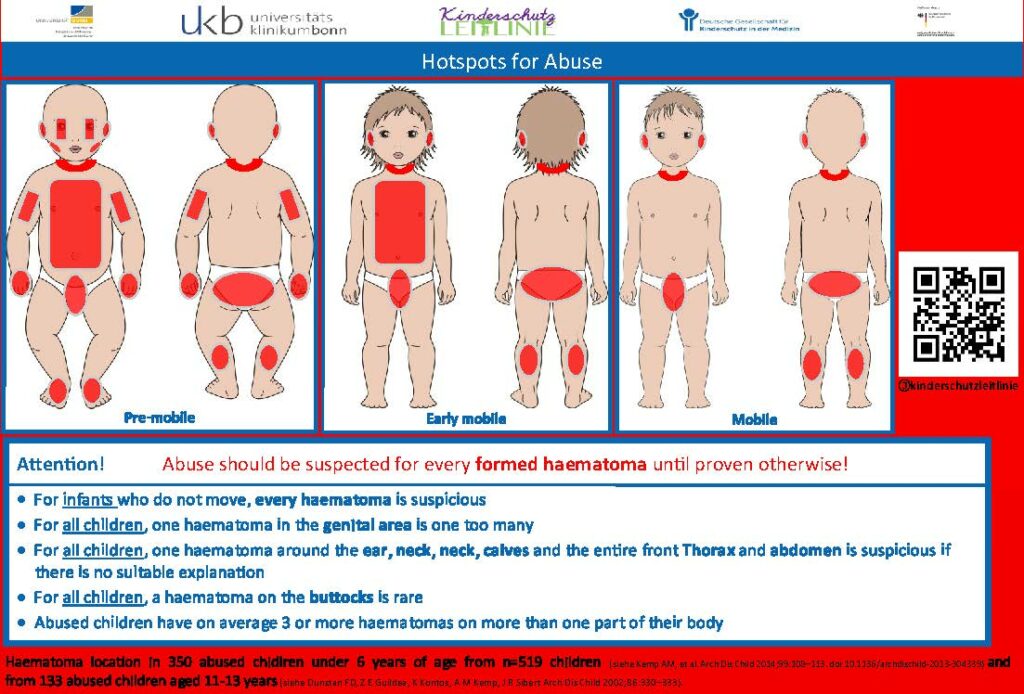

Possible injuries

- Described history is not consistent with injuries.

- Unusual injuries, e.g.

- Severe injuries of any kind

- Frequent fractures

- Unusual appearance (e.g., patterned injuries, such as bite marks)

- Unusual (“protected”) localisation of injuries (including lips, teeth, oral cavity, eyelids, earlobes, buttocks, genitals, fingertips, etc.)

- Untreated (old) injuries

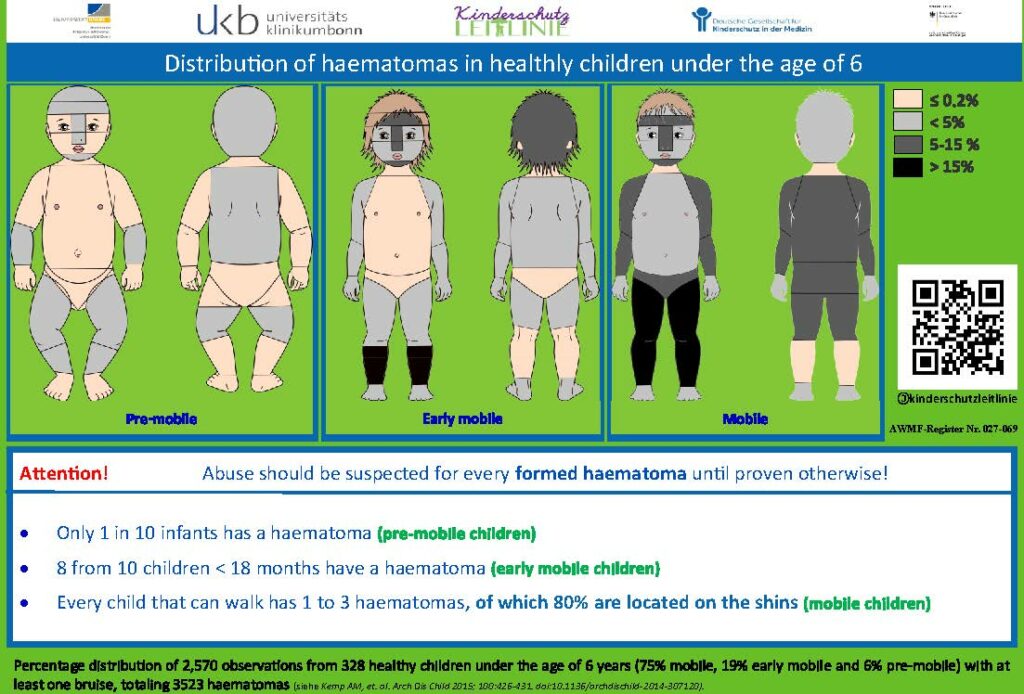

- Unexplained injuries in non-mobile children

- Injury “unusual” for the child’s age; healthy /infants do not have bruises. Even small, medically irrelevant bruises indicate inappropriate handling of the child

- Injuries due to forced or careless feeding

- Contusions (tissue bruising) of the lips or gingiva (due to extreme feeding)

- Burns because the food was too hot

- Forced feeding with bottle: upper incisors intruded lingually, gums show round tear from plastic ring on rubber teat

Caution: Severe internal injuries (e.g., fractures) may lack external injuries! Shaking an infant is life-threatening – and also not externally visible.

Source: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Kinderschutz in der Medizin (Kitteltaschen https://dgkim.de/?page_id=243)

Possible indications regarding the caregivers or parental behaviour(1)

- Psychological abnormalities/illnesses in the parents/mother/father

- Signs of parental issues (e.g., aggression, potential for violence, delinquency, lack of education, marital conflicts)

- Families experiencing psychosocial stressors (e.g., poverty, unemployment, early and/or single parenthood, linguistic isolation, multiple births, child developmental delays)

- Substance use (regardless of the substance) and other addictions in parents (e.g., gambling, sexual, and shopping addiction)

- Inability of parents to correctly interpret and respond to signals from a /infant/child; inability to meet the needs of the new-born/infant/child; lack of attachment to the new-born /infant/child

- Lack of cooperation/therapy compliance on the part of parents e.g.:

- Failure to follow recommendations of the medical personal, inadequate care of chronically ill children by parents

- Failure to administer (regular) medication to the child, skipping the child’s check-up appointments

- Failure to attend (follow-up) appointments after illness/injury, frequent unexcused absences from treatment appointments; conspicuously frequent cancellations of treatment appointments

| Red flags that should make you alert:(4) • Noticeable hematomas are a concern in non-mobile infants. • In any child, having a hematoma in the genital area is concerning. • In any child, having hematomas in multiple regions such as the area of the ear, neck, nape of the neck, calves, and the entire front of the thorax and abdomen is excessive and suspicious if there is no appropriate medical history available. • In any child, having a hematoma in the buttocks area is very rare. Abused children typically have three or more hematomas in multiple regions. |

Case Study: Children at serious risk in domestic violence households

This case is about Daniel, a 4-year-old boy, and his mother Ms. Luscak, aged 27 years who had four different partners. She misuses alcohol and depicts occasional violence towards her partners. She speaks little English. Daniel had 2 siblings, a 7-year-old sister Anna by mum’s first partner and a 1-year-old brother Adam by mum’s fourth partner, Mr. A. On 27 different occasions, the police were called to domestic violence incidents often complicated by both parents being drunk. On 2 occasions Daniel’s mum took sleeping pill overdoses with the intention of committing suicide. The family moved house on numerous occasions due to an inability to pay rent. When pregnant with Adam, Mr. A. urged Ms. Luscak to have a termination. She missed 4 antenatal appointments. At one stage she was hospitalised and Mr. A took the drip out of her arm and she self-discharged.

Daniel had a spiral fracture to the left arm reported as due to jumping off the settee with his sister the previous when being seen at the emergency room. Bruises on his shoulder and lower tummy were explained by his mother to be due to falling off his bike regularly. Meetings of health care professionals took place but the long history of domestic violence was not considered. When Daniel started school, there were frequent absences as for his sister Anna. Teachers became concerned as Daniel was getting markedly thinner and always seemed hungry, taking food from lunchboxes of other children. Daniel had poor English and was a shy and reserved boy and did not talk to the teachers.

Task of reflection

(1) Reflect on the numerous signs and red flags presented in Daniel’s case. What were the early indicators of potential abuse, and how might they have been identified sooner?

(2) What were the missed opportunities for intervention and support of healthcare professionals? How could it have been done better?

Case adapted from The Medical Women’s International Association’s Interactive Violence Manual

6. Frequent indicators in the school sector

- Verbal statements, visible injuries, behavioural problems, or changes in behaviour of a child or adolescent may raise the suspicion that domestic violence could be present in a family.

- Educators, school social workers and teachers should be sensitised for this.

- In any case, the primary goal should be to end the violence against a child, an adolescent, or a parent.

- In most cases of domestic violence, the best way to help the child or the adolescent is for the parent itself to change the situation. Encouraging them to do so and giving them access to help is an important task in the school sector.

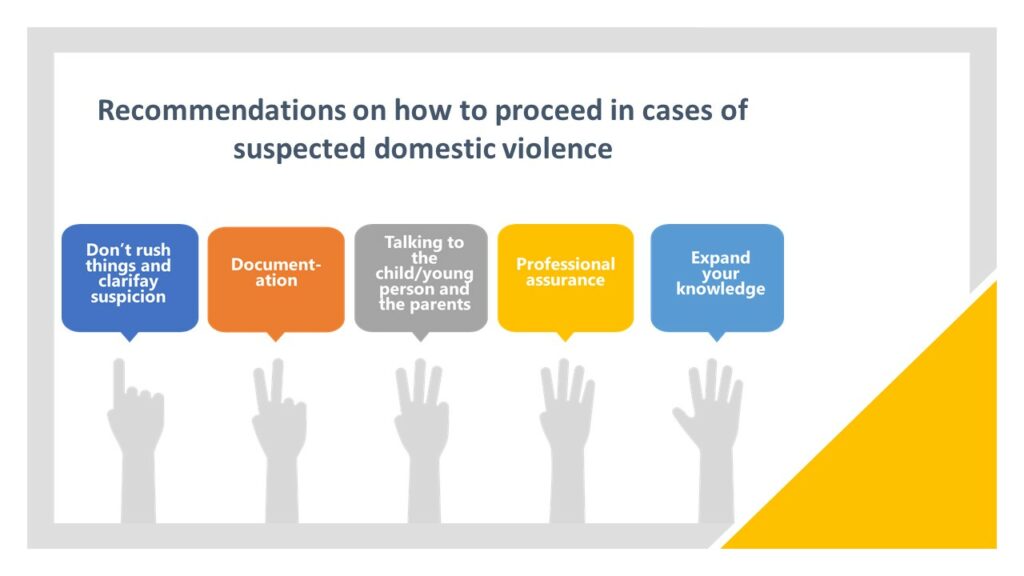

Possible steps for dealing with suspected domestic violence

- Observation of behavioural problems of a child or an adolescent

- Documentation

- Reflection on the observation

- Assumptions about possible causes for the child’s or adolescent’s behaviour (forming hypotheses)

- Involvement of a colleague

- Team meeting (collegial consultation)

- Involvement of the management

- Decision on how to proceed and agree on further steps of action

The last step, “decision on how to proceed and agree on further steps of action”, must be organised individually depending on the case. One possibility would be to talk to the respective child’s or adolescent’s mother and/or father. In the first place, the observed and documented behavioural problems of the child or the adolescent should be discussed. If it becomes clear that the mother or father could be affected by domestic violence, then it is important to have another conversation with him or her in private. Confidentiality should always be assured and information about help options such as counselling centres, anonymous telephone counselling, etc. should be given.

The cooperation with the mother and father as educational partners should be very sensitive and thus be secured in the long term. If mothers and/or fathers are not willing to work on the problems and make use of help offers, then cooperation with other institutions without the parents’ consent is only possible if the child’s or adolescent’s well-being seems to be at risk. Otherwise the school must guarantee data protection. However, it is possible to get advice from different help organisations by phone or in person without revealing the data of the family concerned. If the child’s or adolescent’s well-being is at risk, the youth welfare office must be informed. The child’s or adolescent’s well-being takes precedence over data protection. Also, for the clarification of a possible endangerment of the child’s or adolescent’s well-being, the youth welfare office can first be consulted while preserving the anonymity of the family concerned, to then be able to decide on further steps, e.g., to officially involve the youth welfare office.

Don’t rush things

You can discuss your own feelings, uncertainties and fears with colleagues, counselling centres or the district youth welfare office. Be careful and cautious with your suspicions to avoid uncontrolled actions by other people. Everything you do must be in the best interest of the child or young person.

Clarify suspicion

Conspicuous behaviour can also have very different reasons: a child or adolescent may be in a difficult life situation, perhaps parents are getting divorced, or important caregivers such as grandparents have died. However, a possible cause for conspicuous behaviour can also be witnessing domestic violence or being a victim of domestic violence. It is always important to ask yourself the following: what is the basis for the suspicion? Are abuse, neglect, sexual abuse, or domestic violence the only explanation for the child’s or adolescent’s behaviour? Are there are other possible causes?

Example: physical violence

Alice always has some kind of injury – mostly bruises. The other children have also noticed this. Anyone who asks the five-year-old girl about it always gets new explanations and stories that all have one thing in common: apparently, it is always she herself who has sustained the injuries in her clumsiness. Sometimes she fell down the stairs, sometimes she fell off her bicycle.

But anyone who knows Alice knows that she is anything but clumsy. The teacher also becomes suspicious, because the explanations do not really “fit” the injuries. The other children tell her that Alice’s parents are strict. They punish their daughter for little things like being late. She is not allowed to make any appointments.

When Alice does not come to the day care centre one day, the teacher dares to visit her at home. The parents refuse to let her into their home and say that the child is not there. She then calls the police, who find Alice locked in her nursery, covered in bruises and welts, her mouth taped shut with parcel tape. When the police ask how the massive head injury came about, the parents explain that their daughter had run into the cupboard with her head out of anger.

Source: Handout to promote the recognition of child abuse and the adequate handling of suspected cases (only in German)

Example: psychological violence

Tom is actually quite fat for his eleven years. He has less and less contact with his classmates and no longer takes part in any group activities. It is not the others who tease him, but Tom, who withdraws more and more. He is frighteningly passive.

He also participates less and less in class and seems somehow insecure and afraid. When his transfer is threatened, the parents are invited to a meeting at school. Only the mother shows up for the meeting.

During the conversation with the teacher, it quickly becomes clear that she has a very distant attitude towards her son. She disparagingly calls him stupid and ugly. With regard to his transfer, she indifferently says, “If he doesn’t change, he will have to bear the consequences.”

After the conversation with the teacher, Tom meets his mother and the teacher as he is leaving the classroom with his class. His mother speaks to him in front of the teacher and his classmates, “You’re useless, I’m only in trouble because of you. “

Source: Handout to promote the recognition of child abuse and the adequate handling of suspected cases (only in German)

Example: neglect

Late again! Leo sneaks into the classroom and hopes that the teacher doesn’t notice that he hasn’t managed to arrive on time again. It’s not the first time that the twelve-year-old has been late for school, and he nods off several times during the first lesson. Books and exercise books: missing! Most of the time, he doesn’t have a packed lunch either. He has long since outgrown his trousers, his jumpers are worn out, and no one wants to sit next to him. “You stink!”, the others say.

The teacher is worried about the boy, who seems somehow neglected, but the mother does not respond to her letters. She also ignores the parents’ evenings. But when the teacher asks Leo himself, he always has conclusive explanations ready as to why the mother can’t come.

When Leo’s little sister, who attends the same school, is supposed to take part in a school trip, but the referral of the payment is not made, an appointment is made with the mother, the teacher, and the youth welfare office at the school. The mother does not show up, whereupon Leo is asked about her whereabouts. Then the boy breaks down crying and reports that the mother has been living with her boyfriend for three quarters of a year and only shows up at the flat now and then to leave five euros for groceries. During this entire period, Leo has had to bear the responsibility for the entire household, the totally neglected flat and his three younger siblings.

Source: Handout to promote the recognition of child abuse and the adequate handling of suspected cases (only in German)

Expand your knowledge

Inform yourself through further training on this topic to reduce your own uncertainties and fears.

Here you can find further education and training offers in the field of domestic violence in the social sector.

Case study: Domestic violence has a negative impact on children

Gabby married her husband Nick after a long relationship and shortly thereafter moved to her husband’s family farm. The couple was happy at the farm and soon had their first child. During the pregnancy Nick’s behaviour began to change and by the time their daughter was born the relationship did not ‘feel’ as it had before. Nick seemed withdrawn and spent long periods of time by himself. He began to remind Gabby of Nick’s father who had always been a stern presence in his life.

Nick’s behaviour became threatening and controlling, especially in relation to money and social contact. He was increasingly aggressive in arguments and would often shout and throw objects around the room. Gabby thought that, because he wasn’t physically hurting her, his behaviour did not qualify as abuse. Nick did not show much interest in their daughter, Jane, except when in public, where he would appear to be a doting and loving father.

Jane was generally a well-behaved child, however, Gabby found that she was unable to leave her with anyone else. Jane would cry and become visibly distressed when Gabby handed her to someone else to be nursed. This was stressful for Gabby, and also meant that her social activities were limited further.

Jane took a long time to crawl, walk and begin talking. Her sleeping patterns were interrupted, and Gabby often did not sleep through the night, even when Jane was over 12 months of age. When Jane did begin to talk, she developed a stutter, and this further impeded her speech development. Gabby worried about Jane a lot. Their family doctor told her that this was normal for some children and that, if the speech problems persisted, she could always send Jane to a specialist at a later date.

After a number of years, Nick’s behaviour became unacceptable to Gabby. During arguments he would now hold on to the rifle that he had for farming purposes, and Gabby found this very threatening. On a number of occasions, items that Nick threw hit Gabby and she was increasingly afraid for their daughter. Gabby decided to leave and consulted the local women’s service, who assisted her to get an intervention order against Nick.

Once Gabby had taken Jane away from Nick, her behaviour changed. Jane’s development seemed to speed up and Gabby couldn’t understand why. As part of her counselling at a local women’s service, she discussed this issue, and her counsellor recognised the developmental delay, stutter, irritation, and separation anxiety as effects of Jane’s previously abusive situation.

This can be seen as a missed opportunity for identifying family violence. If the family doctor would have asked Gabby or Nick (who had presented with chronic back pain) about their relationship, about what was happening to the family, and specifically to Jane, the situation could have been identified much earlier.

Tasks

(1) What forms of domestic violence are present?

(2) What indicators of domestic violence can be seen in the case study?

(3) How do you assess the risk for Gabby and her daughter?

The wide range of professionals, provider services and specialist agencies who may be involved in supporting victim-survivors of domestic violence can include—but are not limited to—primary and secondary health care services, mental health services, sexual violence services, social care, criminal justice agencies, the police, probation, youth justice, substance misuse, specialist domestic violence agencies, children’s services, housing services and education.

Adapted from a case study from RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice

Sources

1. Signs of unhealthy relationships

2. Impact of domestic violence

(1) Mellar, B. M., Hashemi, L., Selak, V., Gulliver, P. J., McIntosh, T. K. D., & Fanslow, J. L. (2023). Association Between Women’s Exposure to Intimate Partner Violence and Self-reported Health Outcomes in New Zealand. JAMA network open, 6(3), e231311. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.1311

(2) Danese A, Widom CS (2023). Associations Between Objective and Subjective Experiences of Childhood Maltreatment and the Course of Emotional Disorders in Adulthood. JAMA Psychiatry. Published online July 05, doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2140

(3) Stiles, Melissa. (2003). Witnessing domestic violence: The effect on children. American family physician. 66. 2052, 2055-6, 2058 passim.

(4) Moylan CA, Herrenkohl TI, Sousa C, Tajima EA, Herrenkohl RC, Russo MJ (2010). The Effects of Child Abuse and Exposure to Domestic Violence on Adolescent Internalizing and Externalizing Behavior Problems. J Fam Violence. 25(1):53-63. doi:10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9

(5) Monnat SM, Chandler RF (2015). Long Term Physical Health Consequences of Adverse Childhood Experiences. Sociol Q. 56(4):723-752. doi:10.1111/tsq.12107

(6) Vargas, L. Cataldo, J., Dickson, S. (2005). Domestic Violence and Children . In G.R. Walz & R.K. Yep (Eds.), VISTAS: Compelling Perspectives on Counseling. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association; 67-69. https://www.counseling.org/docs/disaster-and-trauma_sexual-abuse/domestic-violence-and-children.pdf?sfvrsn=2

(7) Lee, V.M., Hargrave, A.S., Lisha, N.E. et al (2023). Adverse Childhood Experiences and Aging-Associated Functional Impairment in a National Sample of Older Community-Dwelling Adults. J GEN INTERN MED https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08252-x

(8) Felitti V.J. et al (1998), ‘The Relationship of Adult Health Status to Childhood Abuse and Household Dysfunction’, American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Vol. 14, pp. 245-258

James, M. (2001), ‘Domestic Violence as a Form of Child Abuse: Identification and Prevention’, Issues in Child Abuse Prevention, 1994; Herrera, V. and McCloskey, L. ‘Gender Differentials in the Risk for Delinquency among Youth Exposed to Family Violence’, Child Abuse and Neglect, Vol. 25, no.8, pp. 1037-1051

Anda, R.F., Felitti, V.J. et al. (2001)‘Abused Boys, Battered Mothers, and Male Involvement in Teen Pregnancy’, Pediatrics, Vol. 107, no. 2, pp.19-27.

3. Excursus: Outsiders as witnesses of domestic violence

4. Indicators

Mota-Rojas D, Monsalve S, Lezama-García K, Mora-Medina P, Domínguez-Oliva A, Ramírez-Necoechea R, Garcia RdCM (2022). Animal Abuse as an Indicator of Domestic Violence: One Health, One Welfare Approach. Animals. 12(8):977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12080977

Hegarty (2011): Intimate partner violence – Identification and response in general practice, Aust Fam Physician. 2011 Nov;40(11):852-6.

Ali, McGarry (2019): Domestic Violence in Health Contexts: A Guide for Healthcare Professions, DOI:10.1007/978-3-030-29361-1

Department of Health and Social Care (2017): Responding to domestic abuse: A resource for health professionals: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/597435/DometicAbuseGuidance.pdf

RACGP (2014): Abuse and Violence: Working with our patients in general practice: https://www.racgp.org.au/clinical-resources/clinical-guidelines/key-racgp-guidelines/view-all-racgp-guidelines/white-book

UN Women, UNFPA, WHO, UNDP and UNODC (2015): Essential services package for women and girls subject to violence – Module 2: Health essential services. https://www.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/Headquarters/Attachments/Sections/Library/Publications/2015/Essential-Services-Package-Module-2-en.pdf

Women’s Legal Service NSW (2019): When she talks to you about the violence – A toolkit for GPs in NSW: https://www.wlsnsw.org.au/wp-content/uploads/GP-toolkit-updated-Oct2019.pdf

Western Australian Family and Domestic Violence Common Risk Assessment and Risk Management Framework (2023), Factsheet: https://www.wa.gov.au/system/files/2021-10/CRARMF-Fact-Sheet-2-Indicators-of-FDV.pdf

5. Frequent indicators in children

(1) https://www.aerzteblatt.de/nachrichten/124955/Bei-Missbrauchsverdacht-Koalition-in-NRW-will-Schweigepflicht-lockern, accessed 10. October 2023

(2) Hegarty (2011): Intimate partner violence – Identification and response in general practice. Aust Fam Physician . 2011 Nov;40(11):852-6.

(3) Mota-Rojas D, Monsalve S, Lezama-García K, Mora-Medina P, Domínguez-Oliva A, Ramírez-Necoechea R, Garcia RdCM (2022). Animal Abuse as an Indicator of Domestic Violence: One Health, One Welfare Approach. Animals. 12(8):977. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12080977

(4) Institut für Qualität im Gesundheitswesen Nordrhein „Notfall- und Informationskoffer: Kinderschutz in der Arztpraxis und Notaufnahme“ https://www.aekno.de/fileadmin/user_upload/aekno/downloads/2023/Kindernotfallkoffer.pdf

6. Frequent indicators in the school sector

Böhm, Christian (2013/2014): Kooperation von Jugendhilfe und Schule im Bereich Kinder- und Jugendschutz. In: IzKK-Nachrichten (1), S. 20–25.

Buchholz, Thomas (2011): Kinderschutz bei Kindeswohlgefährdung als Aufgabe von Schule und Jugendhilfe. In: Jörg Fischer, Thomas Buchholz und Roland Merten (Hg.): Kinderschutz in gemeinsamer Verantwortung von Jugendhilfe und Schule. 1. Aufl. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag, S. 93–116.

Buschhorn, Claudia; Rüsch, Detlef (2018): Kindeswohlgefährdung und Kinderschutz. In: Herbert Bassarak (Hg.): Lexikon der Schulsozialarbeit. Baden-Baden: Nomos, S. 277–278.

Violence against children and adolescent – What to do? A guide for Berlin educators and teachers (only in German)

Handout to promote the recognition of child abuse and the adequate handling of suspected cases (only in German)