1. Barriers to Disclosure

2. Communication Strategies

3. Screening Questions for Domestic Violence

4. Responding to a Disclosure

5. Questions that Often Arise in the Context of DV

6. Visual Communication

Spotlight on the school sector: Communication with parents & pupils

Sources

Target group

This module primarily offers educational materials and pedagogical tools for professionals who train social service professionals working with individuals affected by domestic violence (DV) in their daily practice. It is intended exclusively for professionals in this sector and not designed for individuals experiencing DV or those in their immediate social environment.

Brief overview of Module 3

Module 3 provides an overview of “communication in cases of domestic violence (DV)”. This module presents the critical aspects of communication when addressing DV. Understanding the complexities related to disclosure, employing effective communication strategies, and crafting appropriate responses are paramount in providing comprehensive support to victims of DV. A focus on communication within the school sector, specifically with parents and pupils, is included for those training teaching professionals.

The objectives trainers can address with the materials of Module 3 are as follows:

+ Help trainees gain a better understanding of the existing barriers that may prevent individuals from disclosing DV.

+ Enhance trainees’ ability to apply visual communication methods to facilitate communication in cases of DV.

+ Enable trainees to use screening questions to identify cases of DV.

+ Equip trainees with communication strategies tailored to the specific challenges of DV cases.

+ Guide trainees in responding appropriately and empathetically to disclosures of DV, ensuring that victims feel supported and understood.

+ Deepen trainees’ understanding of the next steps to take when victims disclose violence.

1. Barriers to Disclosure

2. Communication Strategies

“Never assume and always ask!”

The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP)1

3. Screening Questions for Domestic Violence

If an interpreter is needed:

- Never use a victim’s relative or friend as an interpreter.

- Preferably, engage a professional interpreter with DV training or an advocate affiliated with a local specialised DV agency.

- Choose an interpreter of the same gender as the patient, and contemplate having them sign a confidentiality agreement to uphold privacy and trust.

Guidelines how to work with interpreters can be found under these links:

- https://www.tahirih.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Guidelines-for-Working-with-Interpreters.pdf

- Sheffield-Guidance-for-Use-of-Interpreters-in-situations-of-Domestic-and-Sexual-Abuse-FINAL-May-16.pdf (sheffielddact.org.uk)

- https://www.police.qld.gov.au/sites/default/files/2018-10/DFV_InterpreterGuidelinesFinal%20Approved%20v1.0.pdf

4. Responding to a Disclosure

5. Questions that often arise in the context of DV

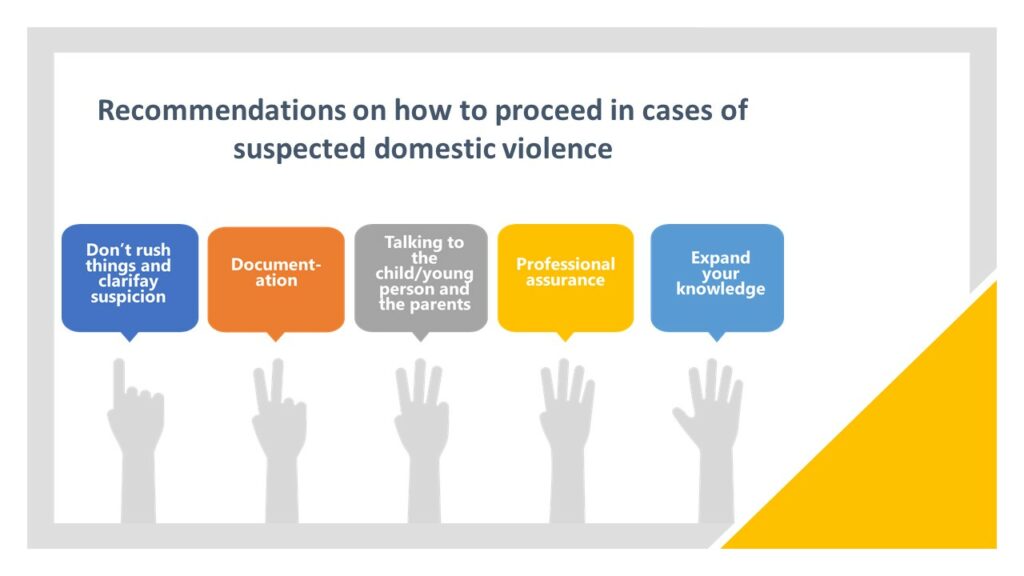

6. Visual Communication

Poster

Leaflet

Business card

Other

Talking to the child or young person

Preparation

- Who conducts the conversation? Who is trusted by the child or adolescent?

- Which setting is appropriate (walk, conversation at the table, …)?

- Is there a room where a pleasant atmosphere can be created?

- How can I help the child or adolescent to make a good transition into everyday life after the conversation?

- Do you need notes and pens, handkerchiefs, information material or similar?

- Are there counselling centres for the suspected problem? Inform yourself.

- Put yourself in the child’s or adolescent’s shoes: does he/she want to have the conversation? Does he/she want to have it alone or in the presence of another person? Has he/she already talked about this with someone else?

Phase 1: Introduction

- Seek contact and speak with the child or adolescent.

- Use the child’s or young person’s language level and ask open questions (no alternative or suggestive questions). Encourage the child or adolescent to tell you about their situation at home. “Incidentals” that say something about rules and control can give you an idea of the child’s or adolescent’s living situation.

- “How are things at home?”/”Many children having behavioural issues at school have problems at home. Is there anyone in your family who puts pressure on you?”

- “How do you get along with your parents/siblings/other family members?”

- “Is there anything that makes you sad or that you are worried about?”

- “Some children are afraid at home. What do you think makes them being afraid?”/”Are there times when you are afraid at home?”

- Reduce tension by making your concerns clear.

- Agree on the time frame and the goal.

- Talk about the level of confidentiality, if you are taking notes, mention what they will be used for.

Examples

“You made a suggestion the other day about how your mother’s boyfriend is sometimes rough with her when he is annoyed with her. This is still bothering me, so I invited you to talk to me. I want to know if I can help you. What do you think?”

“I’ve noticed for a few weeks now, that you look very unhappy and often seem unfocused and tired in class. The other day, when I was handing out the classwork, you looked very anxious/ashamed. I don’t know how you feel about talking to me about this, but maybe I can be supportive. What do you think?”

Phase 2: Introductory question

- Think of a “first question” that marks an introduction to the topic for the child or adolescent.

- In the best case, the previous questions in the introductory phase have succeeded in creating a good atmosphere for discussion.

Examples

“I wonder if there’s something bothering you that’s keeping you awake. Tell me, what is it like for you to sleep?”

“I had the impression that you were anxious/ashamed the moment, I handed out the classwork, right? Tell me about it.”

Phase 3: Conversation content

- In this phase, listen actively and take the child or adolescent seriously.

- Help the child or adolescent to talk about his/her experiences, feelings and needs. If the child or adolescent does not want to talk, offer to talk at a later time.

- Treat statements made by children or adolescents affected by violence in a non-judgemental way.

- Strengthen the child’s or adolescent’s self-esteem by making clear that violence is never okay and that they are not to blame. Reinforce and confirm that the child’s or adolescent’s feelings are right. Support the child or adolescent in perceiving and respecting their own boundaries and those of others. A secret that is scary and dangerous, that feels scary or threatening, that can give you a stomachache or even nightmares, is not a real secret – you are allowed to talk about it, even if you promised not to.

- “Violence is never okay.”

- “It’s not your fault.”

- “You are allowed to feel angry/sad/insecure/etc.”

- “You may talk about it, even if you promised not to.”

- “We will do something together to get help.”

- Believe the child or adolescent. Listen carefully and do not trivialise anything. Tell the child or adolescent that it is helpful to talk about it.

- “I believe you.”

- “I’m glad you came to me.”

- “I’m so sorry that happened.”

- Support the child or adolescent in proposing their own solutions and respect their decisions as long as the child’s or adolescent’s welfare is not at risk.

- Support the child or adolescent in creating a “contingency plan”.

Examples

“The most important thing for me is to know how you are dealing with it. It would be nice if you could say something about it.”

“You say it’s your fault when your parents fight or your father/mother hits you/shouts at you from time to time because you provoke him/her. What do you mean?”

“How can we make sure that you are not put in danger if there is violence between your parents?”

“Who can you turn to if there is violence between your parents? Is there a neighbour? Does a grandma/uncle live nearby? Do you have a telephone?”

Phase 4: Rounding off

- Come back to the goal of the conversation, it must be clear whether there will be a continuation or what the further procedure will be. Coordinate further activities with the child or adolescent, if possible.

- Be sure that when seeking support from the child’s or adolescent’s parents or other confidants that this is done with the child’s or adolescent’s consent and does not aggravate the child’s or adolescent’s situation. Ask about the child’s or adolescent’s relationships with father, mother, siblings, other relatives, friends, and acquaintances. Cautiously establish contact with the child’s or adolescent’s family or caregivers.

Examples

“The 30 minutes are almost up, and it’s time to finish. What else would you like to talk about? Is there anything else I should know?”

“I’ve noticed that it hasn’t always been easy for you, but …”

“I think we had a good talk. Now I know what’s going on. Maybe it would be good if I asked you again, like in a week, how you are?”

“I thank you for telling me so much/ … for being so honest/ … for having the courage to tell me all of this, because it must have been very hard for you.”

“I will invite your mother for a talk as we discussed. We will also stay in contact.”

“I’m still thinking about what to do with the information and I’ll consult with Ms. Meyer. I’ll keep you informed on any further steps.”

Tips for difficult situations

Silence

- Accept if the child or adolescent cannot talk or wants to remain silent on the topic.

- It is good for them to know that pauses in conversations are allowed.

Conflicts of loyalties

- Respect the child’s or adolescent’s loyalties.

- Name violent behaviour, speak out clearly against it.

- At the same time, respect the people involved.

Secrecy request

- Never engage in secrecy.

- Remember: violence is a child protection issue!

- Discuss the next steps with the child or adolescent.

Talking to the parents

Preparation

Helpful attitude in the conversation

- Show appreciation to the parents. Remain free from reproaches and accusations.

- Always critically examine your own experiences and personal attitudes towards domestic violence.

- Question your own attitude towards the family.

- “Am I inwardly aggressive towards the parents?”, “What could contribute to this?”

- “Am I interested in what they have to say about the problems – or not?”

- “Am I sensitive enough to their fears and can I understand why they would rather not talk about it?”

- The conversation’s focus is the concern for the child or adolescent.

- Start the conversation with the child’s or adolescent’s (and the parents’, if applicable) resources. It should not be so much about finding out what exactly happened, but rather about making sure that the conversation is as future-oriented as possible.

Preparations for the parent interview

- If you suspect domestic violence in the family, invite only the parent you suspect to be the victim of the violence.

- Collect and document what you or your colleagues have observed.

- Exchange information with colleagues who are involved with the affected child or adolescent.

- If necessary, seek advice from a specialised agency.

- Have information material, flyers, help addresses at hand.

- Think about how to deal with your fear that the situation will get worse for the child or adolescent if you talk to him/her.

- If necessary, inform the school administration, also to get “back up” for your further action.

- In an invitation, offer the conversation to the parents as an exchange about the child’s or adolescent’s development.

- Consider what you will do if the interview does not take place.

- Put yourself in the parents’ perspective: how do they possibly see the situation?

- Develop your own suggestions for solving the problem or take the children’s or adolescent’s wishes into account. In this context, also inform yourself about the various support options.

Phase 1: Opening the conversation

- State the occasion and the goal of the conversation.

- Talk about the time frame.

Example

“We have invited you to talk about your daughter today. We all want her to be well and to develop well. Together with you, we would therefore like to think about what everyone can contribute to this.”

Phase 2: Clarification of the situation

- Think of an opening sentence with which to start the parent interview.

- Do not bring up the topic of responsibility right away; from the parents’ point of view, this is the topic of guilt!

- Share your concern for the child or adolescent rather than focusing on any misbehaviour on the part of the parent.

- “Do you sometimes worry about …?”

- “She/he seems so depressed sometimes and we don’t know why.”

Example

“I have observed for about two and a half months now, that your daughter has changed: she no longer reports to class, seems withdrawn and has written a D in the last three tests. Do you have any idea what the reason could be?”

- Actively address possible fears of the parents and counter them with factual information without playing down the behaviour that endangers the child’s or adolescent’s well-being or making it a taboo.

- Name possible hurdles.

- “I can understand why this conversation is difficult for you.”

- “We can see that your child is injured. Let’s think about how we can make sure this doesn’t happen again.”

- “I can see that you are injured, and I am concerned about you and your child.”

- Conduct the discussion with “open cards” and inform the parents that the youth welfare office may have to be informed if there is a risk.

- Try to take away the parents’ fear of this and focus on the help that the family can receive.

Examples

“I can understand that this conversation is difficult for you. It’s about your child and family matters, people don’t like to talk about that … I have to admit, it’s hard for me, too!”

“We are having a difficult conversation … You don’t know what I will do if you tell me there are problems at home … But I can assure you that I will discuss further steps with you.”

- If you are planning a confrontation with a suspicion of domestic violence, leave out the term “violence”.

Examples

“Sometimes the reason why children don’t do well at school is because of the home context. Is that a possibility? Is it possible that your daughter is worried? For example, about you?”

“It may be that I am quite wrong now. But I wonder if it is possible that your husband/partner is putting pressure on you. Is it possible?”

- Concealing or trivialising reactions are understandable at first.

- When talking to parents, please leave all interpretations and assessments out of it!

- Mutual questioning and listening are especially important in this phase!

Examples

“We assume that what your son/daughter tells us is true. However, the point is not to clarify what happened, but what should happen to make your child feel better. What can make that happen?”

“With what we observe, we are obliged to react. It must be ensured that your daughter/son can develop healthily. How can this be done?”

“This conversation is to help everyone in the family feel better. Sometimes there are situations where you don’t react appropriately. Now we want to think about how this can be changed.”

“This conversation is to help your daughter/son get better. We want to think about what we can all do to help.”

Phase 3: Finding solutions

- Collect ideas for further action with the parent(s).

- Propose your ideas to them.

Phase 4: Agreement

- If you feel that personal limits are being reached so that continuing the conversation is not possible, it is a good idea to adjourn the conversation to a later time.

- This interruption gives everybody the opportunity to “reflect what has been said”.

- Every conversation should end with the agreement to continue the conversation.

- In the case of suspected violence in the family, it must be made clear that you want to offer help and support, especially for the child/adolescent, as well as to show the adults involved that there is always a way out and that help is available even though the situation is obviously difficult.

- Agree on specific arrangements and record them in writing.

- If necessary, arrange a follow-up appointment to check compliance.

- Agree on a plan of action that is realistically linked to the parents’ possibilities.

When do I not conduct a parental interview but inform the youth welfare office directly?

- Suspicion of sexual abuse within the family

- Acute danger/crisis situation

Professional assurance

In cases of suspected domestic violence, you can contact counselling centres, youth welfare offices and other contact persons for support. If you are sure that the situation poses a high risk for the child or the adolescent, you must protect him/her, and involve the youth welfare office after consultation with the school management. Local and regional support systems have proven their worth in protecting children and adolescents from abuse and neglect. “Institutionalised cooperation” takes place through working groups in which specialists from youth welfare organisations, schools, the police, the judiciary, health and welfare offices, child and youth psychiatry, and the medical profession meet regularly to coordinate their actions.

Sources

- The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners (RACGP). Program material. www.racgp.org.au/familyviolence/resources.htm ↩︎

- Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence (2016). Working together for gender equity and social justice in King County,

Screening for Domestic Violence. www.endgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Screening-for-Domestic-Violence-00000002.pdf ↩︎ - Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence (2016). Working together for gender equity and social justice in King County,

Screening for Domestic Violence. www.endgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Screening-for-Domestic-Violence-00000002.pdf ↩︎ - Rhodes, K. V., Frankel, R. M., Levinthal, N., Prenoveau, E., Bailey, J., Levinson, W. (2007). „You’re not a victim of domestic violence, are you?” Provider patient communication about domestic violence. Ann Intern Med., 147(9), 620-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-0000 ↩︎

- Ashur, M. L. (1993). Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA, 269(18), 2367. ↩︎

- Ashur, M. L. (1993). Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA, 269(18), 2367. ↩︎

- Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence (2016). Working together for gender equity and social justice in King County.

www.endgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Screening-for-Domestic-Violence-00000002.pdf ↩︎ - Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence (2016). Working together for gender equity and social justice in King County.

www.endgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Screening-for-Domestic-Violence-00000002.pdf ↩︎ - Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence (2016). Working together for gender equity and social justice in King County.

www.endgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Screening-for-Domestic-Violence-00000002.pdf ↩︎ - Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence (2016). Working together for gender equity and social justice in King County.

www.endgv.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Screening-for-Domestic-Violence-00000002.pdf ↩︎ - Ashur, M. L. (1993). Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA, 269(18), 2367. ↩︎

- Ashur, M. L. (1993). Asking about domestic violence: SAFE questions. JAMA, 269(18), 2367. ↩︎

- Rhodes, K. V., Frankel, R. M., Levinthal, N., Prenoveau, E., Bailey, J., Levinson, W. (2007). „You’re not a victim of domestic violence, are you?” Provider patient communication about domestic violence. Ann Intern Med., 147(9), 620-7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-9-200711060-0000 ↩︎

- Thackeray, J., Livingston, N., Ragavan, M. I., Schaechter, J., Sigel, E., Council on Child Abuse and Neglect, & Council on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention (2023). Intimate Partner Violence: Role of the Pediatrician. Pediatrics, 152(1). doi.org/10.1542/peds.2023-062509 ↩︎

- Safe + Equal. Identifying family violence. www.safeandequal.org.au/working-in-family-violence/identifying-family-violence/ ↩︎

- World Health Organization (2014). Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence. A clinical handbook. www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136101/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2BA58E813B52A1105271DB988D1AAC88?sequence=1 ↩︎

- World Health Organization (2014). Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence. A clinical handbook. www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136101/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2BA58E813B52A1105271DB988D1AAC88?sequence=1 ↩︎

- World Health Organization (2014). Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence. A clinical handbook. www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136101/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2BA58E813B52A1105271DB988D1AAC88?sequence=1 ↩︎

- World Health Organization (2014). Health care for women subjected to intimate partner violence or sexual violence. A clinical handbook. www.apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/136101/WHO_RHR_14.26_eng.pdf;jsessionid=2BA58E813B52A1105271DB988D1AAC88?sequence=1 ↩︎

- Nadia, E. (22/04/2020). This Secret Signal Could Help Women in Lockdown with Their Abusers. www.refinery29.com/en-ca/2020/04/9699234/domestic-violence-quarantine-coronavirus-signal-help ↩︎