5. Victims of domestic violence

Victims in the dynamics of domestic violence in relationships

Diverse spectrum of victim groups

6. Perpetrators of domestic violence

“The campaign to end domestic violence needs the voices of men as well as women, challenging the cultural, economic and political context in which we all experience the world”

HRH, the Duchess of Cornwall at the Women of the World Festival (March 2020), National Centre for Domestic Violence, UK

Definition

A perpetrator is a person who commits, or knowingly allows, acts of abuse, neglect, or exploitation to occur. An act can also be triggered by a third party.

Sources

Training materials to be used for a workshop or for your self-study can be found here.

General

- Hester, M. (2013) Who does what to whom? Gender and domestic violence perpetrators in English police records. European Journal of Criminology, 10(5), pp. 623-637

- Myhill, A. (2017) ‘Measuring domestic violence: Context is everything’, Journal of Gender-Based Violence, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 33–44

- Walby, S. and Towers, J. (2017) Measuring violence to end violence: mainstreaming gender. Journal of Gender-Based Violence, 1(1), pp. 11-31

Excursus – Gender

- EWL European Coalition Factsheet Istanbul Convention

- EWL Factsheet Violence against Women and Girls in Europe

- Violence against women prevalence estimates, 2018. Global, regional and national prevalence estimates for intimate partner violence against women and global and regional prevalence estimates for non-partner sexual violence against women. Geneva: World Health Organization, on behalf of the United Nations Inter-Agency Working Group on Violence Against Women Estimation and Data (UNICEF, UNFPA, UNODC, UNSD, UNWomen); 2021.

- Pioneers in skirts: https://www.pioneersinskirts.com/ is a multi-award-winning social impact film about the issues that affect a woman’s pioneering ambition. Real-life stories and frank commentary leave viewers seeing their role in the solution, feeling hopeful, and motivated to act.

- RESPECT Women: Preventing violence against women – Implementation package

- Vienna Declaration on Femicide

- UNODC

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/gender-equality/gender-based-violence/what-gender-based-violence_en

- Galdas, P. M., Cheater, F., & Marshall, P. (2005). Men and health helpseeking behaviour: literature review. Journal of Adomestic violenceanced Nursing, 49(6), 616-622

Most common forms of violence in the context of domestic violence

Special types of violence in the context of domestic violence

- http://www.haut-conseil-egalite.gouv.fr/IMG/pdf/violences-couple.pdf (Language: French)

- https://www.vie-publique.fr/sites/default/files/rapport/pdf/014000292.pdf (Language: French)

FGM/C

- https://www.unhcr.org/media/too-much-pain-female-genital-mutilation-and-asylum-european-union-statistical-overview

- https://eige.europa.eu/gender-based-violence/female-genital-mutilation?language_content_entity=en

- Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilation: Report of the Secretary-General (2022)

- FGM study: More girls at risk but community opposition growing (2021)

- FGM study: More girls at risk but community opposition growing (2021)

- Intensifying global efforts for the elimination of female genital mutilation: Report of the Secretary-General (2022)

Femicide

- (1): UNODC, 2019 https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and-analysis/gsh/Booklet_5.pdf

- (2): Dayan H. Female Honor Killing: The Role of Low Socio-Economic Status and Rapid Modernization. J Interpers Violence. 2021 Oct;36(19-20):NP10393-NP10410. doi: 10.1177/0886260519872984. Epub 2019 Sep 15. PMID: 31524058.

CAPVA

- (1) https://www.london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/comprehensive_needs_assessment_of_child-adolescent_to_parent_violence_and_abuse_in_london.pdf

- (2) Rutter, N., Hall, K., & Westmarland, N. Responding to child and adolescent-to-parent violence and abuse from a distance: Remote delivery of interventions during Covid-19. Children & Society. 2023;37:705–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12622

Reproductive coercion

- (1): Grace KT, Anderson JC (October 2018). “Reproductive Coercion: A Systematic Review”. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 19 (4): 371–390. doi:10.1177/1524838016663935. PMC 5577387. PMID 27535921.

Diverse spectrum of victim groups

People with disability, impairment and mental illness

- (1)https://safelives.org.uk/sites/default/files/resources/Disabled_Survivors_Too_Report.pdf

- Personal stories of autistic people as victims of violence

Elderly abuse/maltreatment

- https://www.helpguide.org/articles/abuse/elder-abuse-and-neglect.htm

- http://criminal-justice.iresearchnet.com/crime/domestic-violence/elder-abuse-by-adult-children/

- https://www.nursinghomeabusecenter.com/elder-abuse/signs/

- https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-07-16/royal-commission-abuse-of-elderly-is-under-reported-by-victims/6625230

- http://www.combatingelderabuse.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Booklet_stage.pdf

- Anetzberger, G.J., (2000) Caregiving: Primary Cause of Elder Abuse? Generations, 24 (2): 46–51

- Dong XQ and Simon MA (2014) Vulnerability Risk Index Profile for Elder Abuse in Community-Dwelling PopulationJ Am Geriatr Soc. 2014 Jan; 62(1): 10–15

- Laakso, S., (2015). Ikäihmisten kaltoinkohtelu Suvanto-linjan puheludokumenteissa. University of Helsinki, Faculty of Social Sciences. Dissertation.

- Uuttu-Riski, Ritva, (2004). Vanhusten kaltoinkohtelu – tiedotusvälineissä käyty keskustelu. Teoksessa Kankare, Harri & Lintula, Hanna (toim.) Vanhuksen äänen kuuleminen. Helsinki: Tammi.

Honour-related violence

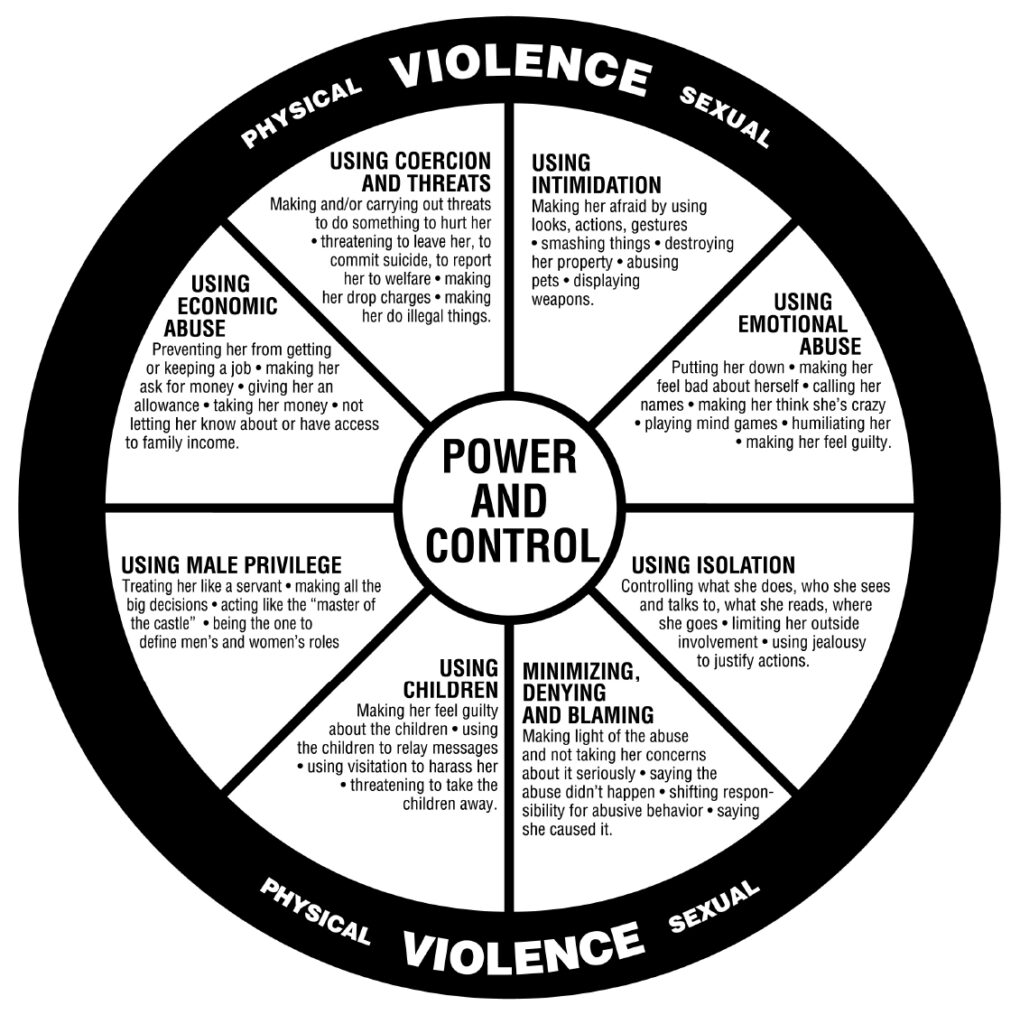

Perpetrators of domestic violence

The wheel of Power and Control

(1) Wheel of Power and Control

Women as perpetrator

(1) Gerke J, Lipke K, Fegert JM, Rassenhofer M. Mothers as perpetrators and bystanders of child sexual abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2021 Jul;117:105068. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105068. Epub 2021 Apr 17. PMID: 33878645.

Relationship between children and the perpetrator and it’s impact