Over 1 in 5 women discloses information on her situation of domestic violence to their general practitioner.

You may be the only person the victim will tell.

Your skills and sensitivity are essential.

Learning objectives

The aim is to give an overview on how patients and their children can be identified as victims of domestic violence and how to respond to them appropriately. It also presents possible indicators of domestic violence and its physical and psychological consequences. The introduction also includes guidelines for patient care and some legal information relevant to the medical sector. The learning materials are not tailored to the individual situation of different countries; they include rather generic cases that will need local adaptation.

IMPRODOVA: Domestic violence in health services

The video describes the various steps on how to proceed in cases of domestic violence in the health sector.

Case Study: Disclosure of domestic violence to the primary care physician

Sabrina is an accountant, 30 years old, married to a construction worker for 8 years now. She tells her primary care physician about her low energy level and headaches that have affected her for over a year. The headaches have gotten worse in the past month (since her husband was laid off), affecting her mostly at the end of the day. She has trouble sleeping and reports pain all over. She has been to several medical practices in the past year but has not found anything that could help her. She has had blood tests, been prescribed painkillers, been advised to get more exercise and change her diet. She desperately needs something to be done for her today as her husband is getting impatient with the lack of results. She is concerned he will become very angry with her when she returns home today. Sabrina’s doctor asks, ‘What happens when your partner gets angry?’ She has never been asked this question and Sabrina hesitates to answer. Her doctor says, ‘I would really like to hear what is going on at home.’ Sabrina bursts into tears, and the story of her experience with partner violence slowly unfolds. After the doctor assessed the risk according to the procedures defined for such cases, he makes sure that Sabrina currently is not in danger of escalating violence and Sabrina confirms she feels she can manage what is happening for now. Right now, she does not want to go to a shelter or contact the police. The physician suggested these options, even though the risk of a violent outbreak is not very high at the moment. He wants her to have all the information available to make a good choice. They make a follow-up appointment for ongoing support and the doctor gives her the number of a helpline if anything should happen until their next appointment.

For more case studies and scenario-based learning click here.

What is domestic violence?

Domestic violence is an abuse of power within a domestic relationship, between relatives or ex-partners. It involves one person dominating or controlling another, causing intimidation or fear, or both. Domestic violence is often experienced as a pattern of abuse that escalates over time.

It is not necessarily physical and can include:

- emotional or psychological abuse

- verbal abuse

- spiritual abuse

- including taking part in their religious or cultural practices, misusing spiritual or religious beliefs and practices to justify abuse and violence

- stalking and intimidation, including using technology

- social and geographic isolation

- sexual abuse

- financial abuse

- cruelty to pets

- damage of property

Power and Control Wheel developed by the Domestic Abuse Intervention Programs (DAIP)

The Power and Control Wheel illustrates the most common abusive behaviors and tactics.

Understanding the Power and Control Wheel

Module 1 provides detailed information on the forms and dynamics of domestic violence.

Indicators

The following are indicators associated with victims of domestic violence. Please note that none or all of these might be present and be indicators of other issues. Using these indicators as a guide can complement the practice of asking directly.

Physical indicators of potentially being a victim of domestic violence in adults:

- unexplained bruising and other injuries

- especially head, neck and facial injuries

- bruises of various ages

- injuries sustained do not fit the history given

- bite marks, unusual burns

- injuries on parts of the body hidden from view (including breasts, abdomen and/or genitals), especially if pregnant

- chapped lips

- teeth knocked out

- miscarriages and other pregnancy complications

- chronic conditions including headaches, pain and aches in muscles, joints and back

- sexually transmitted infection and other gynaecological problems

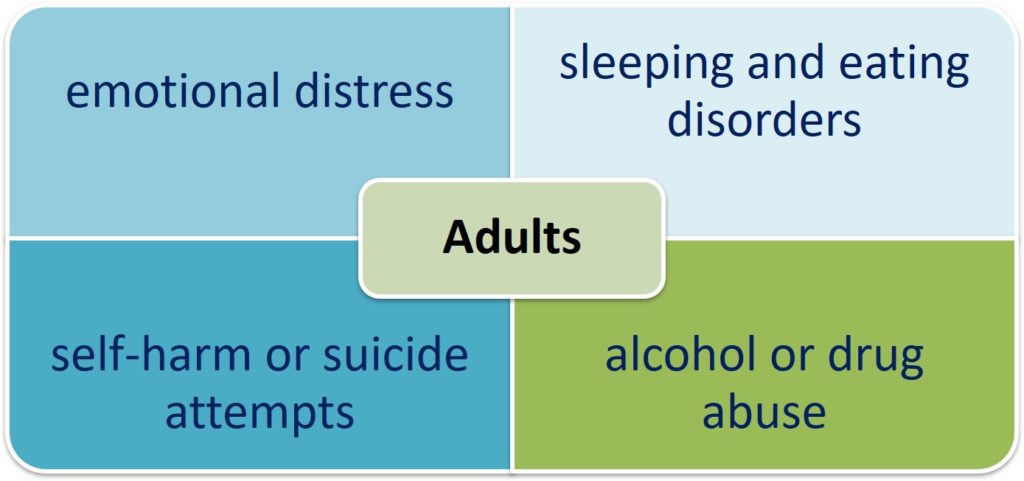

Psychological indicators of potentially being a victim of domestic violence in adults:

- emotional distress, e.g., anxiety, indecisiveness, confusion and hostility

- sleeping and eating disorders

- anxiety/depression/pre-natal depression

- psychosomatic complaints

- self-harm or suicide attempts

- evasive or ashamed about injuries

- multiple presentations at the emergency room/client appears after hours

- partner or other family member does most of the talking and insists on remaining with the patient

- seeming anxious in the presence of their partner

- reluctance to follow advise

- social isolation/no access to transport

- frequent absence from work or studies

- submissive behaviour/low self-esteem

- alcohol or drug abuse

- fear of physical contact

- nervous reactions to physical contact/quick and unexpected movements

Physical indicators of potentially being a victim of or witnessing domestic violence in children:

- difficulties eating/sleeping

- slow weight gain (in infants)

- physical complaints

- eating disorders (including problems of breast feeding)

- fingertip injuries

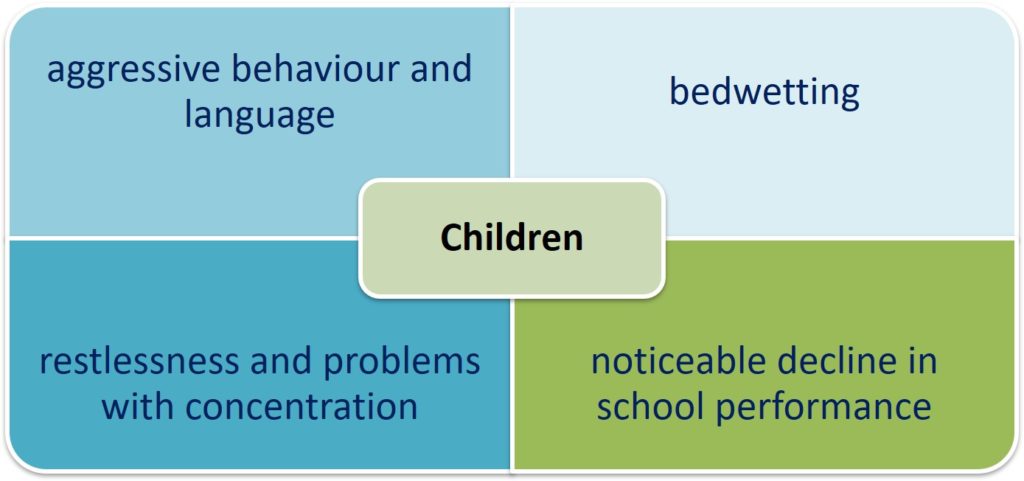

Psychological indicators of potentially being a victim of or witnessing domestic violence in children:

- aggressive behaviour and language

- depression, anxiety and/or suicide attempts

- appearing nervous and withdrawn

- difficulty adjusting to change

- regressive behaviour in toddlers

- delays or problems with language development

- psychosomatic illness

- restlessness and problems to concentrate

- dependent, sad or secretive behaviours

- bedwetting

- ‘acting out’, for example cruelty to animals

- noticeable decline in school performance

- fighting with peers

- overprotective or afraid to leave mother/father

- stealing and social isolation

- sexually abusive behaviour

- feelings of worthlessness

- transience

Routinely check the patient’s medical history to see if there have been previous hospital visits with similar injuries or complaints.

Further information: Matoori, S., Khurana, B., Balcom, M.C. et al. Intimate partner violence crisis in the COVID-19 pandemic: how can radiologists make a difference?. Eur Radiol (2020)

Possible indicators of sexual violence

- injuries to the genitals, the inside of the thighs, the breasts, the anus

- irritations and redness in the genital area

- common infections in the genital area

- pain in the lower abdomen and/or pelvic area

- sexually transmitted diseases

- bleeding in the vaginal or rectal area

- pain when urinating or defecating

- pain when sitting or walking

- strong fears of examinations in the genital area; avoidance of examinations

- severe cramps in the vaginal area during gynaecological examinations

- sexual problems

- self-harming behaviour

- unwanted pregnancies/abortions

- complications during pregnancy

- miscarriages

Module 2 deals with indicators of domestic violence in more detail.

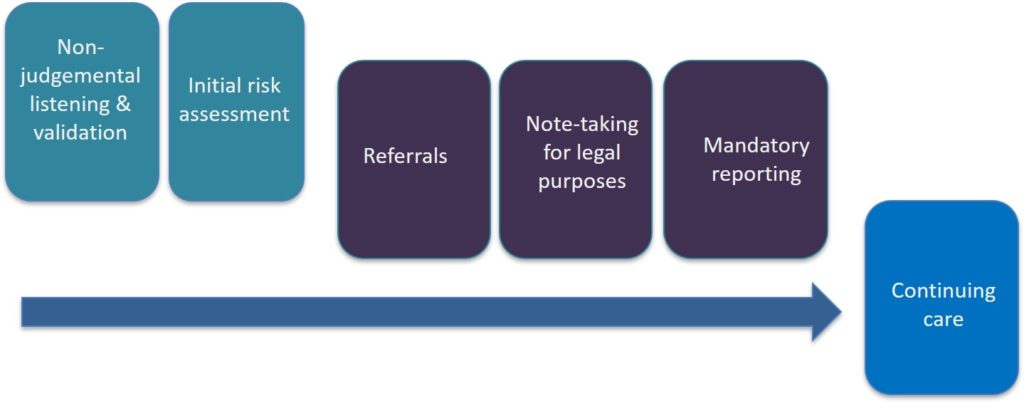

Stages of effective response

- Non-judgmental listening and validation

- Initial safety assessment

- Referrals, e.g., to the Police, to the Domestic Violence Line, to legal advice, to victim support (only with the victim’s consent)Note-taking for legal purposes if the victim wants to take legal steps

- Mandatory reporting – if required

- Continuing care

How to talk to your patient about domestic violence

In any situation that you suspect underlying psychosocial problems, you can ask about domestic violence indirectly or directly. If you are concerned that your patient is experiencing domestic violence, you should ask to speak with them alone, separate from their partner or any other family members. It is important to understand that the victim very often blames herself/himself or tries to protect the perpetrator. If a situation makes you suspicious, you can always ask broad questions about whether your patient’s relationships are affecting their health and wellbeing. Listen to them non-judgmentally and back them up.

For example:

- ‘How are things at home?’

- ‘How are you and your partner (or other family members) getting along?’

- ‘How do you argue when you are at home?’/’Can you disagree with your partner?’

- ‘Is there anything else happening which might be affecting your health?’

It is important to realise that some victims, who have been abused, want to be asked about domestic violence. They give hints and are more likely to disclose if they are being asked in a safe environment. If appropriate, you can ask direct questions about any violence.

For example:

- ‘Are you afraid when you are at home?’/‘Are there ever times when you are frightened of your partner (or other family members)?’

- ‘Are you concerned about your safety or the safety of your children?’

- ‘Does the way your partner (or other family members) treats you make you feel unhappy or depressed?’

- ‘Has your partner (or other family members) ever verbally intimidated or hurt you?’

- ‘Has your partner (or other family members) ever physically threatened or hurt you?’

- ‘Has your partner (or other family members) forced you to have sex when you didn’t want it?’

- ‘Violence at home is very common. I ask a lot of my patients about abuse, because no one should have to live in fear of their partner.’

If you see specific clinical symptoms and you are sure that your suspicions are correct, you can ask specific questions about them (e.g. bruising). These could include:

- ‘You seem very anxious and nervous. Is everything alright at home?’

- ‘When I look at your injuries, I wonder if someone could have hurt you?’

- ‘Is there anything else that we haven’t talked about that might be contributing to this condition?’

If your patient’s fluency in your mother tongue is a barrier to discussing these issues, you should work with a qualified interpreter. Don’t use your patient’s partner, other family members or a child as an interpreter. It could compromise their safety or make them uncomfortable to talk about their situation with you.

How to talk to victims of domestic violence is the subject of module 3. For more information, please visit this module.

Responding to disclosure

Your immediate response and attitude when your patient discloses domestic violence can make a difference. Victims require an initial response to disclosure: they need somebody to listen to them, back them up and ensure their children’s safety. They also need to be shown a pathway to safety.

Listen

Being properly listened to can be an empowering experience for a victim who has been abused. The key aspect of proper listening is a non-judgmental attitude. Acknowledge that the victim is the expert on the subject of his/her own life and his/her experiences. He/she should not be pushed into making decisions.

Communicate believing them

‘That must have been frightening for you.’

Validate the decision to disclose

‘I understand, it is very difficult for you to talk about this.’

Emphasise the unacceptability of violence, but do not judge the perpetrator

‘Violence is unacceptable. You do not deserve to be treated this way.’

Be clear that the victim is not to blame

Avoid suggesting that your patient is responsible for the violence or that they can control the violence by changing their behaviour.

Do not ask questions that might raise victims’ stress and sense of powerlessness:

- ‘Why don’t you leave?’

- ‘What could you have done to avoid this situation?’

- ‘Why did he/she hit you?’

Aspects that should be considered after the disclosure of domestic violence such as medical assessment and securing of evidence are addressed in module 4.

Initial risk assessment

Assist your patients to evaluate their own and their children’s immediate and future safety. Best-practice risk assessment involves seeking relevant facts about their particular situation and asking them about their own perception of risk. It also includes consulting a professional: you may need to refer your patient to a specialized domestic violence service. The strongest indicator of future risk/violence is current and past behaviours of the perpetrator. You may also advise the patient to go to the police.

It is essential that you engage the victim in a conversation about their perceptions of risk and how they have managed their safety in the past.

Document any plans made for future reference!

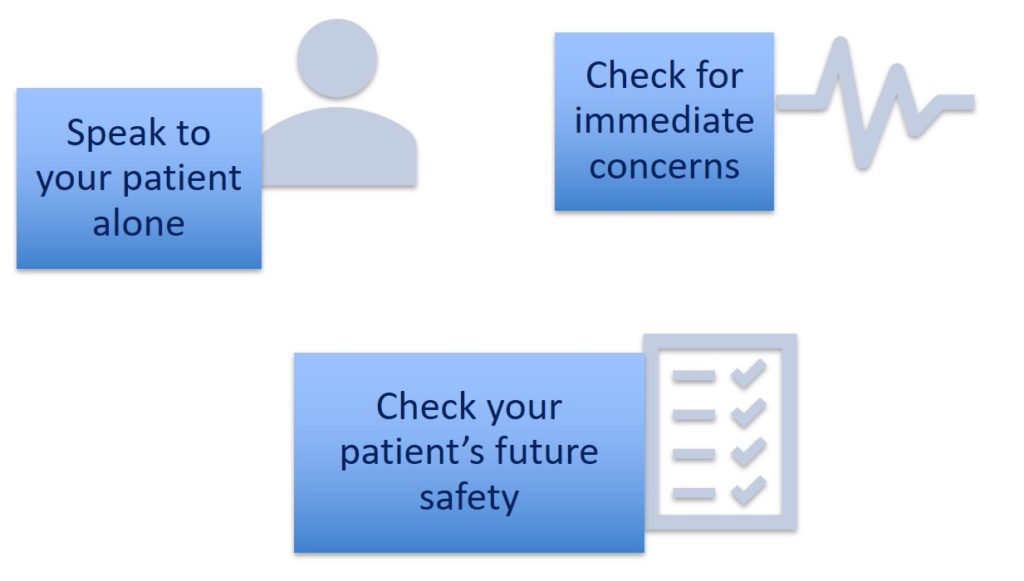

For initial safety planning, you will at least need to:

- speak to the victim in a private setting

- check for immediate concerns

- Does the patient feel safe going home after the appointment?

- Are his or her children safe?

- Does he or she need an immediate place of safety?

- Does he or she need assistance with the next steps towards safety?

- Does he or she need to consider an alternative exit out of your building?

- if immediate safety is an issue:

- victims of domestic violence often feel isolated, depressed and helpless. Therefore, it is extremely important to carefully identify the life situation and needs of the victim.

- If it is necessary, assist the victim to receive immediate crisis help and psychosocial support.

- If your patient’s or their children’s safety are at risk, consider contacting the police.

- Initiate child protection procedures if not in action yet.

- victims of domestic violence often feel isolated, depressed and helpless. Therefore, it is extremely important to carefully identify the life situation and needs of the victim.

- if immediate safety is not an issue, check your patient’s future safety.

- Has the perpetrator caused physical harm before (e.g., by beating)?

- Has the perpetrator’s behaviour changed/escalated recently?

- Does the perpetrator have access to weapons or any other objects to cause serious physical harm?

- Are there any additional current stressors in the perpetrator’s life or factors reducing the perpetrator’s self-confidence?

- Does your patient need assistance to make a referral to the police or legal services?

- Does your patient have emergency telephone numbers?

- Does your patient need a referral to a domestic violence service to help make an emergency plan?

- Where would your patient go if he or she had to leave?

- How would your patient get there?

- What would your patient take with him or her?

- Who is available for your patient to contact for support?

Other elements in safety planning include usual scenarios (e.g., the victim keeps living with perpetrator, the victim wants to leave abusive relationship, and the victim does no longer live with perpetrator).

Risk assessment is an ongoing process. You may need to check in on the victim to follow up on this initial safety plan.

Find more information on risk assessment and safety planning in module 5.

Note-taking for legal purposes

- If the victim wishes to make a report to police: you can support the investigation and future legal proceedings by taking detailed notes.

- Describe physical injuries, including the type, extent, age and location. If you suspect violence is a cause, but your patient has not confirmed this, include a comment and make sure that the explanation accurately explains the injury. If there is an official form or template for documenting domestic violence injuries, please use it.

- Record what the patient said (using quotation marks).

- Record any relevant behaviour observed, be detailed and factual rather than stating a general opinion, e.g., rather than ‘the patient was distressed’, write ‘the patient cried throughout the appointment, shook visibly and had to stop several times to collect herself/himself before answering a question’.

- Consider taking photographs of injuries, or certifying photographs taken of the injuries presented at the time of consultation. Your file notes must include the date and time and clearly identify the client. You must clearly identify yourself as the author and sign the file note. Do not include generalisations or unsubstantiated opinions. Correct and initial any errors, set out your report sequentially. Use approved symbols and abbreviations only.

International standards and legal frameworks in Europe are discussed in more detail in module 6.

Mandatory reporting

If somebody talks about experiencing or perpetrating violence, and you believe you have reason to suspect that a child is at risk of significant harm, you have to report this to Community Services. You are not obliged to report violence experienced by adults. Reporting violence experienced by adults without their consent could put them at greater risk of harm.

Exposing them to domestic violence can have a serious psychological impact on children. In some cases, you may feel there is a risk of significant harm to a child even though it seems unlikely that the violent person in their home would physically hurt them. Use your professional judgment about the individual circumstances and the nature of the violence.

Continuing care

Consider the victim’s safety the paramount issue. You can help to monitor the safety by asking about any previous escalation of violence or physical harm.

Be familiar with appropriate referral services and their processes. The victim may need your help to seek assistance and might need information to take with them.

In module 7 you will find more information on inter-organisational cooperation and risk assessment in cases of domestic violence in multi-professional teams.