1. Importance of self-care

2. Strategies on how to improve self-care

3. Stress

4. Burnout

5. Secondary traumatisation

Sources

Target group

This self-study module is specifically designed for practitioners supporting victims of domestic violence (DV), who wish to study independently and at their own pace.

Brief overview of Module 9

Module 9 provides an overview on self-care.

Working with victims of domestic violence poses significant challenges for frontline responders, often leading to stress, tension, and emotional strain that can potentially result in burnout or trauma if not effectively managed. Thus, it is important to raise awareness of these challenges and develop strategies to address them. Prioritising professionals’ own well-being is as important as taking care of the well-being of victims. Despite the importance of this topic, there is a noticeable lack of comprehensive studies examining work-related stress concerning the work with victims of domestic violence.

Module 9 highlights the risks associated with burnout and vicarious trauma. It explores the interpersonal and organisational boundaries when working with victims of domestic violence, and provides practical coping strategies, empowering professionals to navigate difficult situations while ensuring their self-care remains a priority.

What can be learned in this module?

+ Understand the importance of self-care

+ Develop practical skills for implementing self-care routines and strategies

+ Understand why frontline responders working with victims of domestic violence face high risks of burnout and vicarious trauma

+ Get familiar with risk factors for burnout and vicarious trauma in the context of domestic violence

+ Learn how to recognise the signs and symptoms of stress, burnout, and vicarious trauma

1. Importance of self-care

Working with people who have experienced domestic violence can be extremely mentally challenging. It is quite normal to experience a range of feelings, when working with victims of domestic violence. Being aware of the potential impact on your own wellbeing and taking steps to minimise the negative impacts are important strategies of self-care.

Self-care can be defined as the ability of individuals, families, and communities to promote health, prevent disease, maintain health, and to cope with illness and disability with or without the support of a health worker in form of acceptance and without resignation.1

Difficult situations in the context of domestic violence

Frontline responders play an important role in providing emotional support to victims, improving their safety, and providing legal assistance, but they routinely encounter unpredictable and complex situations and confront a range of challenges while providing support to victims.2

Please click on the crosses to get more information.

Excursus: Dealing with frustrations

Victims of domestic violence very often stay in abusive relationships and find it difficult to allow intervention for various reasons, one of them being a sense of lack of support. This can be exhausting, frustrating, and difficult to handle. Though professionals may feel frustration, they may be their first and only point of contact.3

As a professional working with victims of domestic violence, it is important to address frustration when it arises, taking into consideration the following points:

- Realise early on that the victim may never leave the abuser.

- Recognise that leaving is a process, not an event – the timeline from the beginning of abuse to the point of leaving may take decades.

- Remind yourself, that it is the victim’s responsibility to leave an abuser, not yours.

- Get to know as much as you can about how domestic violence is being addressed at a local level. At the bare minimum, you should know the domestic violence support services in your area, so that you can provide accurate information for victims.

- Do not feel that you have to know everything that there is to know about domestic violence. Listening and communicating support and active contact details for an external support agency is better than not talking about it at all.

- Be aware of your own safety needs. Should a violent incident occur, arrange a staff debriefing session. Violence affects everybody differently.

- Have local contact details for domestic violence support available to all staff members.

- Look after yourself. Working with the effects of domestic violence professionally can bring personal issues to the surface, particularly if you are experiencing or have experienced abuse yourself.

2. Strategies on how to improve self-care

Being prepared for periods of stress can make it easier to get through them and knowing how to manage our wellbeing can help us recover after a stressful event. Resilience refers to our ability to manage stress. It is the process and outcome of successfully adapting to difficult or challenging life experiences, especially through mental, emotional, and behavioural flexibility and adjustment to external and internal demands. A number of factors contribute to how well people adapt to adversities, predominant among them (a) the ways in which individuals view and engage with the world, (b) the availability and quality of social resources, and (c) specific coping strategies.4

There are things we can try to build our resilience against stress. But there are also factors that might make it harder to be resilient, such as experiencing discrimination or lacking support.5

Self-assessment tool: Self-care

Self-care activities are things you do to maintain good health and improve well-being. You will find that many of these activities are things you already do as part of your normal routine.

In this self-assessment you will think about how frequently, you are performing different self-care activities. The goal of this assessment is to help you learn about your self-care needs by spotting patterns and recognising areas of your life that need more attention.

There are no right or wrong answers on this assessment. There may be activities that you are not interested in, and other activities may not be included. This list is not comprehensive but serves as a starting point for thinking about your self-care needs.6,7

Rate yourself, using the numerical scale: 5 = Frequently, 4 = Occasionally, 3 = Sometimes, 2 Never, 1 = It never even occurred to me

How often do you do the following activities?

Physical self-care

- Eat regularly (breakfast, lunch, and dinner)

- Eat healthfully

- Exercise, go for walks, garden, workout at the gym, lift weights, practice martial arts

- Get regular medical care for prevention

- Get medical care when needed

- Take time off when you are sick

- Get massages or other body work

- Do physical activity that is fun for you

- Take time to be sexual

- Get enough sleep

- Wear clothes you like

- Take vacations

- Take day trips or mini-vacations

- Get away from stressful technology (e.g., smartphones, email, social media)

Psychological self-care

- Make time for self-reflection

- Go to see a psychotherapist or counsellor

- Write in a journal

- Read literature unrelated to work

- Do something at which you are a beginner

- Take a step to decrease stress in your life

- Notice your inner experiences (e.g., dreams, thoughts, imagery, feelings)

- Let others know different aspects of you

- Engage in a new area (e.g., go to an art museum, performance, sports event exhibit, or other cultural event)

- Practice receiving from others

- Be curious

- Say no to extra responsibilities sometimes

- Spend time outdoors

Emotional self-care

- Spend time with others whose company you enjoy

- Stay in contact with important people in your life

- Treat yourself kindly (e.g., by using supportive inner dialogue or self-talk)

- Feel proud of yourself

- Reread favourite books, watch favourite movies

- Identify and seek out comforting activities, objects, people, relationships, and places

- Allow yourself to cry

- Find things that make you laugh

- Express your outrage in a constructive way

Spiritual self-care

- Make time for reflection, meditation and/or prayer

- Spend time in nature

- Participate in a spiritual gathering, community, or group

- Be open to inspiration

- Cherish your optimism and hope

- Be aware of non-tangible, nonmaterial aspects of life

- Be open to the unknown

- Identify what is meaningful to you and notice its place in your life

- Sing

- Express gratitude

- Celebrate milestones with rituals that are meaningful to you

- Remember and memorialise loved ones who are dead

- Nurture others

- Have awe-filled experiences

- Contribute to, or participate in, causes you believe in

- Read inspirational literature

- Listen to inspiring music

Professional self-care

- Take time to eat lunch

- Take time to chat with colleagues

- Make time to complete tasks

- Identity projects or tasks that are exciting, growth promoting, and rewarding

- Set limits with colleagues and clients

- Balance your caseload so that you do not “burn out”

- Arrange your workspace so that it is comfortable and comforting

- Get regular supervision or consultation

- Negotiate for your needs

- Have a peer support group

Tasks for reflection

Once you have completed the self-assessment, reflect on the following questions:

(1) Were there any surprises? Did the assessment present any new ideas that you had not thought of before?

(2) Which activities seem like they would be more of a burden than a benefit to you?

(3) What are you already doing to practice self-care in the physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and professional realms?

(4) Of the activities you are not doing now, which particularly sparks your interest? How might you incorporate them into your life sometime in the future?

(5) What is one activity or practice you would like to try starting now or as soon as possible?

Tips for maintaining and managing wellbeing at work8

- Actively engage in regular supervision and collective reflective practice.

- Reach out to someone. This could be your supervisor, a trusted friend or colleague, a counsellor or another support person.

- Find a way to escape physically or mentally including rest, reading, days off, holidays, walks, seeing friends, having fun, and doing things that make you laugh, playing with children and pets, and creative activities.

- Take your scheduled workday breaks, weekends, and annual leave.

- Evaluate your workspace to ensure it is conducive to wellbeing.

- Try to establish boundaries with the work required by the institution or company members that exceed your job functions.

- Practice active communication with your institution or company members about your personal and work situation and make individual or collective demands that you consider fair.

- Be kind and supportive to your colleagues and celebrate achievements.

- Practice self-compassion. In bearing witness to stories of abuse and violence, it is good to remember that an emotional response is also a human one. While it is important to maintain professional composure with victims, emotional responses related to abuse and violence are natural and appropriate. Staying connected with how you feel and having self-compassion will help you to be resilient and sustain your work.

The following strategies are recommended to improve self-care at work.9

Please click on the crosses to get more information.

You can use these specific strategies to improve your self-care.10

Ask for help if you need it

Asking for support can not only help protect your own emotional wellbeing, but it can also mean you are happier and more effective at work.

One of the biggest causes of vicarious trauma is how much time is spent with people who experience trauma. How work is divided among staff within an organisation is very important.

For more information on how organisations can better support staff, see “What managers and organisations can do”, below.

Take a break

There are many ways to take a break. What you do is not important as long as it gives you a chance to relax and recharge.

- Take time to escape (physically or mentally, films, books, holidays)

- Have rest time (down time with no specific goal or time limit)

- Make the most of opportunities to enjoy yourself (develop positive emotions, do things that make you laugh or smile, take part in creative activities, play with children)

Have realistic expectations

When you are doing challenging work or supporting people who need a lot from you, it is easy to take on too much. Remember you are only human, try to keep things in perspective.

- Be aware of the expectations you place on yourself – do they need to be more realistic?

- Accept that you are likely to be affected to a degree by doing demanding work

- Focus on things that are within your control

- Actively problem-solve difficult issues

- Take regular breaks (including each day at work, as well as longer breaks on weekends and for holidays)

- Try to understand yourself and your responses to stressful situations, including how stereotypes about your profession may impact your expectations

Up-skill and seek support

Being confident in your skills and working in a cooperative, supportive workplace are keys to doing your job well. Having the right skills for the job also helps manage stress. There are plenty of ways to improve your skills that do not require formal training.

- Read about or do training in vicarious trauma

- Ask for support from colleagues

- Request regular professional supervision

- Seek variety at work, try different tasks

- Develop professional networks and relationships

- Take this information to your manager or supervisor

Find balance and meaning

It is important to keep a balance in your life and focus on the value of the work that you do. Keeping things in perspective can help make you more resilient and satisfied in both your work and personal life. These simple actions can have a big impact on the way you feel.

- Keep a healthy work-life balance, as well as balancing the types of tasks you do at work

- Remember the importance and value of the work you do

- Be mindful and appreciate the little things (for example a warm day, good coffee, a hug)

- Mark important events, celebrate and grieve with rituals or traditions

- Stay connected with loved ones

- Find small ways to refresh and ground yourself throughout the workday

- Focus on doing your best (instead of only specific goals that ‘must’ be completed)

- Recognise and challenge any cynical beliefs that come up

- Seek out strengths and successes (in yourself, as well as others and the work you do)

- Consider activities to encourage personal growth (for example creative activities, journaling, mindfulness)

- Find what renews you spiritually and connects you to greater meaning (nature, religious belief, community, and family) and do these things regularly

- Try a gratitude journal – at the end of each day write down three things you are grateful for, or three things that went well that day and why they matter

What managers and organisations can do

Managing the risk of burnout and vicarious trauma is an important part of workplace health and safety within an organisation. There are practical and important things that managers can do to support the wellbeing of their staff.11

Two of the most important factors that can prevent burnout and vicarious trauma are:

- How work is allocated

- The support professionals receive

Management support strategies can include:

- Regular supervision and debriefing

- Rostering or alternated appointment systems, which are designed to minimise constant exposure to stressful environments

- Work allocation changes, such as providing duties that are not directly connected to the work with victims

- Establish a yearly rotation system from positions working with victims to positions working with professionals (e.g., teaching duties)

- Professional development opportunities such as workshops on domestic violence, burnout, and vicarious trauma

- Providing professional development pathways or study time – this can help reduce the effects of vicarious trauma, and can also help professionals to feel that their work and skills are valued

- Enhanced collaborative practice and inter-agency case management, so that professionals do not feel they are the only one working with, or responsible for, a victim’s or family’s safety

- Encouragement of self-care, down-time, lunch breaks and other re-fuelling practices

Organisations should have policies and procedures in place to:

- Support professionals’ safety in everyday practice

- Document and debrief reportable and critical incidents

- Address concerns about misconduct, bullying and service quality

Given the high prevalence of domestic violence worldwide, it is highly likely that the workplace includes people with their own past or current lived experiences of domestic violence. Enabling sustainability requires dedicated workplace policies that recognise this reality and include confidential support strategies.

Tasks for reflection

(1) Are you aware of the expectations you place on yourself in your professional role? How might these expectations be influencing your stress levels and overall well-being?

(2) Do you believe your expectations of yourself are realistic given the demands of your work?

(3) How do you perceive the impact of demanding work on your mental health? Are you acknowledging its impact, or do you tend to minimise or ignore it?

(4) What aspects of your professional life do you feel are within your control?

(5) Are you comfortable seeking help and support when needed?

(6) How do you approach stressful situations or obstacles in your work? Are you proactive in finding solutions, or do you tend to feel overwhelmed or stuck?

Relaxation techniques

Relaxation techniques are helpful tools for coping with stress and promoting long-term health by slowing down the body and quieting the mind. Here are three relaxation techniques that can help you to reduce your stress-related symptoms and gain a better sense of control and well-being in your life12:

Deep breathing

Breathing exercises are the simplest path to inner calm. Practicing 15 minutes a day can achieve a significant reduction in your stress-related symptoms. Breathing is one function controlled by both the voluntary and involuntary nervous system, forming a bridge between our inner and outer selves. To use the technique, take several deep breaths and relax your body further with each breath.

Diaphragmatic breathing

By performing this exercise, you engage the diaphragm (the most important muscle of breathing), which increases airflow in your lungs.

Square breathing

Also known as box breathing or 4×4 breathing. This technique is the simplest form of mindful breathing and aims to return breathing to a normal rhythm in only a few minutes.

Progressive muscular relaxation

One of the most popular and easy-to-use methods to relax is by doing progressive muscular relaxation. This approach is useful for relaxing your body when your muscles are tense. The key is to become aware of tension and its corresponding state, relaxation, in each of the body’s muscle groups. First, tense a group of muscles so that they are tightly contracted. Hold the muscles in a state of extreme tension for a few seconds. Then, let the muscles relax normally. Next, consciously relax the muscles even further so that you become as relaxed as possible. By tensing your muscles first, you will find that you are able to relax your muscles more than you could if you simply tried to relax your muscles directly.

Experiment with this method by forming a fist and clenching your hand as tightly as you can for several seconds. Relax your hand to its previous state, then consciously relax it again so that it is as loose as possible. Following this practice, you should feel deep relaxation in your hand muscles.

Relaxation response

The relaxation response, first developed by Herbert Benson, is a simple form of meditation that anyone can use. Follow these steps for 10 to 20 minutes daily to decrease stress in your life and help you focus.

- Sit quietly and comfortably.

- Close your eyes.

- Start by relaxing the muscles of your feet and work your way up to your head, relaxing the muscles.

- Focus your attention on your breathing.

- Breathe in deeply and then let your breath out. Count your breaths to yourself. Or pick a word, phrase, image, or prayer on which to focus. You might also choose to simply focus on your breath moving in and out.

Excursus: Wellbeing during times of crises

The COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted existing structural inequalities throughout Europe, heightening the risks and vulnerabilities associated with domestic violence and revealing the limitations and obstacles within the support system. It has led to a widespread shift to remote services for professionals working with victims of domestic violence, often for the first time, and has posed challenges in maintaining the mental health and well-being of these professionals in remote settings.

Find more information about domestic violence in times of disasters in Module 7.

What are managers’ responsibilities during times of emergency and crisis?

- Managers have a responsibility to ensure the safety and well-being of all professionals, both physically and mentally.

- Managers and supervisors must take steps to protect the mental health of professionals, especially those working remotely or from home.

- Managers should develop and implement strategies to help professionals create safe and suitable remote work environments, promote well-being, and offer support if mental health issues arise during emergencies and crises.

Organisations can take the following actions to improve crisis preparedness, response, and recovery, as well as to mitigate work-related stress, burnout, and other mental health problems during such times.13

Set up safe remote workspaces in professionals’ homes

- Consider the professionals’ preferences regarding remote or face-to-face work in the office.

- Discuss with staff the challenges of working remotely, such as the need for sensitive conversations, potential impact on shared living spaces, feelings of isolation, and stress.

- Ensure staff have the necessary tools and equipment for remote work, including internet access, computers, software, phones, ergonomic furniture, etc.

- Conduct meetings to assess and provide equipment for remote work and develop guidelines for staff to access tools and technology.

- Maintain confidentiality and privacy of client data by implementing secure storage systems for remote work settings.

Monitor and manage professionals’ wellbeing

- Monitor and manage staff well-being during crises, including regularly checking in with professionals, providing dedicated supervision sessions, facilitating peer support, and encouraging breaks from work.

- Supervising practice during emergencies involves focusing on the personal impact of domestic violence work, considering alternative supervision methods, discussing potential trauma spills in shared homes, and extending mental health services to others in shared homes.

- Maintaining social connections is essential by transitioning in-person rituals to virtual versions, scheduling regular team catch-ups via online platforms.

- Adaptive case allocation and management prioritise professionals’ well-being, considering workload, case complexity, and staff availability, and involves regular monitoring and review of caseloads and workloads.

- Staff recruitment during crises requires careful consideration, evaluating previous experience, qualifications, and cultural knowledge before making decisions about recruitment and induction of new staff.

Communicate

- Communication is crucial during crises, and organisations should develop internal and external communication plans to address the challenges faced during emergencies.

- Internal communication plans should establish clear channels for conveying decisions related to case prioritisation and ensure that staff mental health and well-being are prioritised in all communications.

- External communication plans should outline channels for communicating with the public, providing clear and reassuring messages about service changes and availability during the crisis.

- Organisations must consider the impact of service alterations on both clients and staff, providing consistent information through central communication channels and appointing public information spokespeople to coordinate communication with the public, media, and government.

Build a resilient domestic violence workforce

- Prioritise the health and safety of professionals during emergencies and crises by integrating mental health and well-being strategies into crisis response and recovery plans.

- Focus on building resilience in the workforce through systematic planning, implementation, and monitoring of mental health strategies during emergencies.

- As organisations transition from crisis response to recovery, emphasise workforce resilience and agility to adapt to future crises.

- Reflect on past experiences to identify strengths, gaps, and areas for improvement in crisis response, involving input from all levels of the organisation to inform future strategies.

Questions & Answers: Self-care14

What should I do if victims refuse the help provided?

- Accept their wishes.

- Wait for other opportunities, try again later.

- If you cannot find a solution, brainstorm with colleagues (maintain confidentiality).

- Try to say, “I did my best. I feel the need to take some distance aside from the case now.” It is your responsibility to offer pathways, not to take action for the victim.

What should I do if there is not enough information about the violent situation?

- Reconsider which information is crucial to get/are essential and who could provide them.

- Identify risk factors before taking action.

- Brainstorm with colleagues what other sources of information could be used.

- Make a plan for your approach.

- Ensure the atmosphere is conducive.

- Share information and ideas to get responses.

What should I do in cases of danger?

- Consider carefully whether it may be necessary to call the police.

- Inform colleagues and ask for their support.

- If there is immediate danger, call the police immediately.

- In the case of verbal aggression, do not call the police immediately. In cases of physical aggression and when the victim is in danger of life, call the police immediately, otherwise you may encounter problems.

- If there is no immediate danger, try to talk to the victim.

How can I cooperate with and learn from colleagues?

- Be open to new suggestions.

- Use humour.

- Ask your colleague if he/she can give you some insights into his/her work.

- Good meetings with and support from your colleagues can be very fruitful and empowering in cases of violence.

What should I do if I feel that colleagues and/or the immediate supervisor are not supporting me?

- Try to find the right way and tone to say what you want to say.

- Find a way to express your disappointment over a colleague and/or immediate supervisor. Try to not make it personal.

What should I do if I feel tension and negative stress?

- Try to be attentive to “alarm signals”, such as tension in the neck and shoulder area, fatigue, restlessness, sleep problems, nervousness, etc.

- Try to solve the problems on different levels (personal, interpersonal, at the workplace, in the organisation).

What should I do if I bring the problems home?

- Initiate a de-briefing with colleagues.

- Talk to friends, but do not share personal data.

- Relax, take long walks, have a warm bath.

- Take deep breaths.

What should I do if I do not have enough time to manage my workload?

- Ask colleagues for support.

- Talk to your supervisor about reorganising your tasks.

- Propose a team meeting to discuss the issues.

- Try to reorganise yourself.

- Make a commitment to take time for yourself and for your family and friends.

What should I do if I notice these signs of lack of self-care in a colleague?

- Acknowledge and communicate these signs.

- Encourage seeking professional help.

- Promote self-care activities.

- Create a supportive environment.

3. Stress

Domestic violence is a problem for those directly affected but can also pose significant challenges for professionals. Problems, frustrations, and barriers can result in stress, or even burnout, and in some cases in vicarious trauma if not effectively managed. It is important for professionals to be aware of the risks and recognise the signs.

Definition of stress

Stress can be “acute” or “chronic”17:

- Acute stress happens within a few minutes to a few hours after an event. It lasts for a short period of time, usually less than a few weeks, and is very intense. It can happen after an upsetting or unexpected event. For example, this could be a sudden bereavement, assault, or natural disaster.

- Chronic stress lasts for a long period of time or keeps coming back. You might experience this if you are under lots of pressure a lot of the time. You might also feel chronic stress if your day-to-day life is difficult, for example if you are a carer or if you live in poverty or if you experience domestic violence yourself. Additionally, chronic stress can result from working with traumatised people and/or regular exposure to stressful situations at work.

Stress and our body

Stress is our body’s reaction to a pressure situation (acute or chronic). When we are exposed to stress, our body produces stress hormones that trigger a fight or flight response and activate our immune system. The body then reacts with an alarm response. The release of stress hormones (e.g., cortisol and adrenaline) in the brain puts the body on alert and increases blood pressure, breathing and heart rate, among other things.

The following video shows how stress affects our body:

Learn more about how stress affects the brain in particular in the following video:

Signs and symptoms of chronic stress

Too much stress can leave us in a permanent stage of fight or flight, leaving us overwhelmed or unable to cope. Long term, this can affect our physical and mental health and physical, emotional, and behavioural symptoms develop. Our body’s autonomic nervous system plays an important role in some of those symptoms as it controls our heart rate, breathing, vision changes and more.

The body tries to adapt to a prolonged (chronic) stress situation. The following symptoms often occur during this so-called resistance phase:

Physical symptoms of chronic stress

Physical symptoms of stress can include18:

- Faster breathing and heartbeat

- Panic attacks

- Sleep problems

- Muscle aches and headaches

The following video explains what happens to our body and brain when we do not get enough sleep:

As a result of chronic stress, a phase of exhaustion occurs due to the constant excessive demands: The immune system is less efficient, people fall ill more quickly or more often. The risk of developing mental illnesses such as anxiety disorders, burnout or depression also increases.19

Emotional and mental symptoms due to chronic stress

If people are stressed, they might feel these symptoms the most often:

- Feeling irritable, angry, impatient or wound-up

- Being anxious, nervous or afraid

- Unable to enjoy yourself (e.g., you have lost your sense of humour)

- A sense of dread

- Unable to concentrate

- Unable to remember things, or make your memory feel slower than usual

- Constantly worry or have feelings of dread

- Grind your teeth or clench your jaw

- Experience sexual problems, such as losing interest in sex or being unable to enjoy sex

- Withdraw from people around you

Often, people with chronic stress try to manage it with unhealthy behaviours.20

Unhealthy behaviours

If people are stressed, they may observe in their daily life the following:

- Smoke

- Use recreational drugs

- Drink alcohol more than they usually would

The following video explores the stages of how our memory stores information and how short-term stress impacts this process:

Causes of stress

Many things can cause stress. You might feel stressed because of one big event or situation in your life, or it might be a build-up of lots of smaller things. You can have stress from good challenges as well as bad ones.

Some situations that do not bother you at all might cause someone else a lot of stress. This is because we are all influenced by different experiences. We also have different levels of support and ways of coping. Certain events might also make you feel stressed sometimes, but not every time. Some of these situations may be considered even as happy events, but they can still feel very stressful (e.g., getting married or starting a new job).

Stress can occur in different areas of our lives.21 These may include:

Please click on the crosses in the corresponding circles to get more information on potential warning signals in these different areas of life.

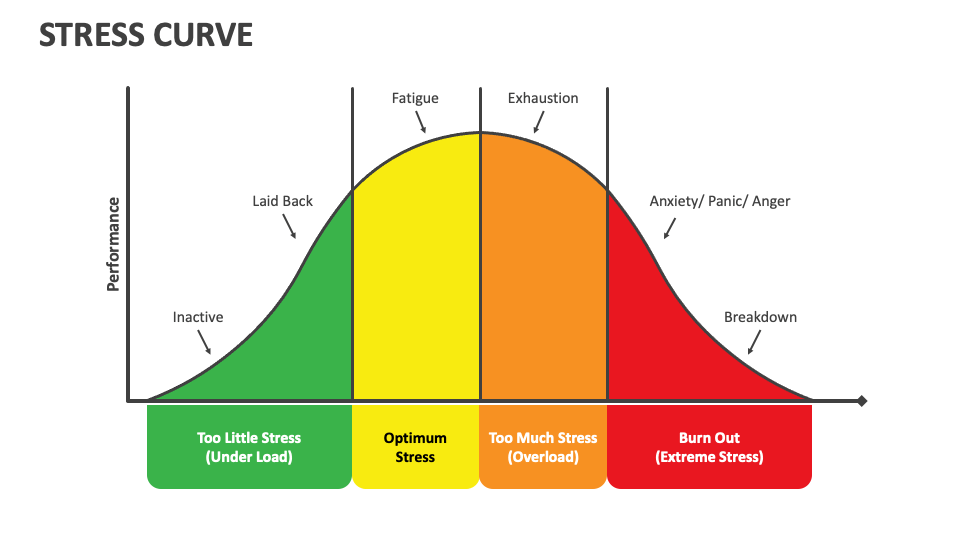

The following illustration shows the progression of a stress curve from too little stress to burnout:

Too little stress

- Inactive: In this phase, stress levels are very low. Individuals might feel bored, disengaged, and lack motivation. There is insufficient pressure to stimulate action or focus.

- Laid back: As stress levels increase slightly, individuals may feel relaxed but still lack the drive to perform. There is minimal urgency or challenge to spur productivity.

Optimum stress

- Stress as a productive force: When stress reaches a moderate level, individuals begin to experience increased energy and focus. This phase is marked by heightened alertness and motivation, leading to high performance. This is the zone of optimal performance where stress acts as a positive force, however this can result in fatigue without any rest.

Too much stress

- Exhaustion: Beyond the optimal point, stress levels become too high, causing performance to decline. Individuals may experience physical and mental exhaustion, leading to decreased productivity. The stress starts to take a toll on the body and mind, making it difficult to maintain high performance.

Burnout

- At this stage, prolonged high stress may result in a complete breakdown. This phase is characterised by physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion.

4. Burnout

Definition of burnout

Some people who go through severe stress may experience suicidal feelings. This can be very distressing. In such situations, it is important to seek professional help, as integrating self-care routines like meditation and exercise may not be sufficient. Primary care physicians can be the first point of contact to help those affected to find ways out of this stress spiral can help navigate these challenging times safely.

The term “burnout” was coined in 1974 by the American psychologist Herbert Freudenberger. He used it to describe the consequences of severe stress and high ideals in “helping” professions. Doctors and nurses, for example, would often end up being “burned out” – exhausted, listless, and unable to cope.22

The ICD-11 of the World Health Organization (WHO) defines burnout as an occupational phenomenon resulting from chronic workplace stress that has not been successfully managed.23 It is classified as a mismatch between the challenges of work and a person’s mental and physical resources, but is not recognised as a standalone medical condition.

Burnout can lead to anxiety, anger, or panic, which may impair ability of those affected to function properly. Finally, chronic stress results in a complete breakdown, which may manifest as severe fatigue, depression, or total withdrawal from activities.

Symptoms that may indicate burnout

There are three main areas of symptoms that are considered to be signs of burnout24:

- Feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion: People affected feel drained and emotionally exhausted, unable to cope, tired and down, and do not have enough energy. Physical symptoms include things like pain and gastrointestinal (stomach or bowel) problems.

- Increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one’s job: People who have burnout find their jobs increasingly stressful and frustrating. They may start being cynical about their working conditions and their colleagues. At the same time, they may increasingly distance themselves emotionally, and start feeling numb about their work.

- Reduced professional efficacy: Burnout mainly affects everyday tasks at work, at home or when caring for family members. People with burnout are very negative about their tasks, find it hard to concentrate, are listless and lack creativity.

Diagnosis of burnout

In 1981, Maslach and Jackson developed the first widely used instrument for assessing burnout, the Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI). It remains by far the most commonly used instrument to assess the condition. The MBI operationalises burnout as a three-dimensional syndrome consisting of emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation (an unfeeling and impersonal response toward recipients of one’s service, care, treatment, or instruction), and reduced personal accomplishment.25

The MBI originally focused on social professionals (e.g., teachers, social workers). Since that time, the MBI has been used for a wider variety of workers (e.g., health professionals). The instrument or its variants are now employed with many other professions.

Learn more about burnout in the following video:

5. Secondary traumatisation

Definition of secondary traumatisation

“Trauma” is an ancient Greek word meaning wound or injury. In psychology, trauma refers to a severe psychological injury. Trauma often arises from experiences where a person is subjected to significant threat and helplessness.26 Secondary traumatisation is the impact of knowledge about another person’s traumatic experience on your own psyche; i.e., a trauma that you did not experience yourself. This occurs usually at a distance from the original trauma and unconscious.

Secondary traumatisation is also known by a handful of other names, including:

- Vicarious traumatisation

- Secondary trauma

- Second-hand trauma

- Secondary traumatic stress

Sometimes it can lead to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or other mental health difficulties, like depression and anxiety.27

Signs and symptoms of secondary traumatisation

Symptoms of secondary traumatisation can be experienced physically, emotionally, and behaviourally:28

- Nightmares with reliving the trauma material of the traumatised person

- Social withdrawal

- Stress-related medical conditions

- Flashbacks stemming from their own traumatic experiences (those affected get a racing heart and dry mouth, can sweat and be just as frightened as they were in the original situation).

Secondary traumatisation can happen to people who engage with trauma survivors or witness traumatic events, especially on a repetitive basis.29 For this reason, seondary traumatisation is common among professionals known for helping others, like therapists, social workers, police officers, firefighters, paramedics, teachers, and doctors.

Who may be particularly at risk of being affected by secondary traumatisation?

- Persons with own previous and unresolved traumas (e.g., domestic violence)

- Situation paralleling one own’s life situation

- Own high level of stress

How can you prevent secondary traumatisation?

- Good self-care

- Good working conditions and collegial teamwork

- Tackling of conscious trauma with professional help

This video introduces secondary traumatisation and its possible effects on work and personal life. It also offers some techniques for addressing work-induced stress and trauma.

The following checklist contains more signs to be aware of.30 The things on the list do not necessarily mean that you are suffering from burnout or secondary traumatisation. An answer of “yes” to any of the questions can alert you to the need to speak to someone to receive support.

Checklist for burnout and secondary traumatisation

- Are your relationships with close friends, family, children, or partners changing for the worse?

- Are you finding yourself irritable, anxious, agitated or “snapping” more frequently than usual?

- Are you worried about your work performance?

- Are you avoiding, or getting anxious about engaging with work, clients, or patients?

- Do you notice mood swings or feel your moods are sometimes out of your control?

- Are you feeling flat, sad, lacking energy, overtired for no reason, or as though you are “spacing out” from things around you when you are stressed?

- Are you getting run down or catching more colds or infections than usual?

- Do you feel unsafe or overly anxious about your safety?

- Are you self-soothing in ways that might be numbing or can cause you increased stress later, such as mindless eating, alcohol or substance use, or smoking?

- Do you feel you have lost hope, or that there is little “goodness” in humanity?

- Do you have nightmares, poor sleep, intrusive thoughts, or images that are upsetting?

Case study: Self-care in the legal sector when dealing with cases of domestic violence

Emily is a dedicated lawyer who specialises in handling cases of domestic violence. She works tirelessly to ensure that victims receive justice and perpetrators are held accountable for their actions. In her role, Emily represents victims in court, assists with obtaining protective orders, and provides legal counsel throughout the legal process.

As a lawyer, Emily is exposed to the harrowing details of domestic violence cases on a daily basis. She listens to victims recount their experiences of abuse, trauma, and fear, which can take a toll on her emotional well-being. She often works long hours, sacrificing her personal time and neglecting her own needs in order to prioritise her clients’ cases. She finds it difficult to switch off from work, constantly thinking about ongoing cases and feeling the weight of her clients’ struggles on her shoulders.

Tasks for reflection

(1) What challenges does Emily face as a lawyer dealing with cases of domestic violence?

(2) Why might it be difficult for legal professionals like Emily to engage in self-care practices? What factors might help Emily recognise her need for support, and how can she be encouraged to seek and accept help?

(3) How can neglecting self-care, such as not setting boundaries at work, impact the performance and well-being of Emily?

(4) What steps could Emily take to improve her self-care and accept support?

(5) How could the legal environment be improved to better support legal professionals like Emily in prioritising their self-care?

(6) What resources and support mechanisms could be implemented within the legal sector to help professionals in similar situations improve their self-care?

Possible answers to the reflection tasks

(1) Emily faces several challenges in practicing self-care, including:

- Emotional toll: Listening to traumatic stories and reliving victims’ experiences can be emotionally draining.

- Long hours: The demanding legal work, including extensive case preparation and court appearances, often leads to long working hours.

- High-stress level: The pressure to ensure justice for victims and hold perpetrators accountable can be highly stressful.

- Personal sacrifice: Emily may neglect her personal needs and social life to prioritise her clients.

- Secondary trauma: Repeated exposure to clients’ trauma can lead to secondary or vicarious trauma.

- Work-life imbalance: Difficulty in switching off from work and constantly thinking about cases contributes to a poor work-life balance.

(2) Legal professionals like Emily might struggle with self-care due to:

- Working culture: The legal field often values dedication and long hours, making self-care seem less important.

- Guilt: Feeling guilty about taking time for herself when clients are in need.

- Perceived weakness: Seeking help or taking breaks might be perceived as a sign of weakness or lack of commitment.

- High workload: Heavy caseloads leave little time for self-care activities.

Factors that might help Emily recognise her need for support include:

- Physical symptoms: Experiencing fatigue, headaches, or other stress-related symptoms.

- Psychological symptoms: Increased irritability, anxiety, or feeling detached from her work.

- Feedback from colleagues: Colleagues or supervisors noticing changes in her behaviour or performance.

- Education and training: Education about burnout and the importance of self-care.

Emily can be encouraged to seek and accept help through:

- Supportive leadership: Encouragement from supervisors and a supportive workplace culture.

- Peer support: Building a network of colleagues who can offer mutual support.

- Access to professional resources: Availability of counselling services.

- Training and workshops: Participating in self-care and stress management workshops.

(3) Neglecting self-care can significantly impact Emily’s performance and well-being, including:

- Physical health issues: Higher susceptibility to illnesses due to chronic stress.

- Mental health issues: Increased risk of depression, anxiety, and other mental health concerns.

- Burnout: Emotional and physical exhaustion, leading to a decrease in job satisfaction and effectiveness.

- Decreased empathy: Reduced ability to empathise with clients, potentially affecting the quality of legal representation.

- Poor decision-making: Reduced ability to make legal decisions, impacting case outcomes.

(4) Emily can take several steps to enhance her self-care and accept support:

- Setting boundaries: Establishing clear boundaries between work and personal life to ensure enough rest.

- Regular self-care activities: Engaging in activities that promote relaxation and well-being, such as exercise, hobbies, and mindfulness practices.

- Seeking professional support: Seeking counselling or therapy to process emotions and stress.

- Peer support: Joining support groups with fellow legal professionals to share experiences and coping strategies.

- Time management: Prioritising tasks and managing time effectively to reduce workload pressure.

- Education on self-care: Attending workshops and training on self-care and stress management techniques.

(5) To help legal professionals like Emily prioritise their self-care, the legal environment can be improved by:

- Promoting a culture of self-care: Encouraging open discussions about self-care and mental health.

- Flexible scheduling: Offering flexible work hours and time-off policies to allow for recovery and personal time.

- Access to wellness programmes: Providing access to wellness programmes that strengthen resources for physical, mental and emotional health, including fitness classes, mental health resources, and stress management workshops.

- Regular supervision and support: Ensuring regular supervision sessions to provide emotional support and professional guidance.

- Workload management: Balancing caseloads to prevent overburdening staff.

(6) Resources and support mechanisms that could benefit legal professionals include:

- Counselling and support services: Providing access to confidential counselling and support services.

- Professional counselling: Offering mental health services tailored to the needs of legal professionals.

- Training and workshops: Conducting workshops on self-care, resilience, and stress management.

- Peer support groups: Creating formal peer support groups for sharing experiences and coping strategies.

- Sabbatical leaves: Providing opportunities for sabbatical leaves to allow for extended recovery time.

- Access to wellness facilities: Access to wellness facilities such as gyms, relaxation rooms, and quiet spaces for reflection and relaxation.

All sectors include different case studies. Visit Module 9 for the police, health sector, and social sector to find out more.

Sources

- Word Health Organization. 2022. Self-care interventions for health. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/self-care-interventions-for-health ↩︎

- Ferreira, E., Figueiredo, A. S., and Santos, A. 2023. Understanding the Emotional Impact and Coping Strategies of Professionals Working with Domestic Violence Victims. Social Sciences 12(9), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090525 ↩︎

- Ferreira, E., Figueiredo, A. S., and Santos, A. 2023. Understanding the Emotional Impact and Coping Strategies of Professionals Working with Domestic Violence Victims. Social Sciences 12(9), 525. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090525 ↩︎

- American Psychological Association (APA). 2018. APA Dictionary of Psychology. Resilience. https://dictionary.apa.org/resilience ↩︎

- Mind. 2022. Stress. Managing stress and building resilience. https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/stress/managing-stress-and-building-resilience/ ↩︎

- Therapist Aid. 2018. Self-Care Assessment. https://www.therapistaid.com/worksheets/self-care-assessment ↩︎

- Homeless and Housing Resource Center (HHRC). 2023. Self-Assessment Tool: Self-Care. https://hhrctraining.org/system/files/paragraphs/download-file/file/2022-06/HHRC%20Handout_Self%20Care%20Assessment%20Tool%20-%20Updated_508.pdf ↩︎

- Equal + Safe. 2024. Prioritising your wellbeing. https://safeandequal.org.au/working-in-family-violence/wellbeing-self-care-sustainability/prioritising-your-wellbeing/ ↩︎

- 1800 Respect. 2024. Wellbeing and self-care. https://www.1800respect.org.au/resources-and-tools/wellbeing-and-self-care ↩︎

- 1800 Respect. 2024. Preventing work-induced stress and trauma. https://www.1800respect.org.au/resources-and-tools/work-induced-stress-and-trauma/preventing ↩︎

- Equal + Safe. 2024. Employer responsibilities. https://safeandequal.org.au/working-in-family-violence/wellbeing-self-care-sustainability/employer-responsibilities/ ↩︎

- Homeless and Housing Resource Center (HHRC). 2023. Self-Assessment Tool: Self-Care. https://hhrctraining.org/system/files/paragraphs/download-file/file/2022-06/HHRC%20Handout_Self%20Care%20Assessment%20Tool%20-%20Updated_508.pdf ↩︎

- Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Domestic Violence Victoria & Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria. 2021. Best Practice Guidelines: Supporting the Wellbeing of Family Violence Workers During Times of Emergency and Crisis. Monash Gender and Family Violence Prevention Centre, Monash University, Victoria, Australia.

https://bridges.monash.edu/articles/online_resource/Best_Practice_Guidelines_Supporting_the_Wellbeing_of_Family_Violence_Workers_During_Times_of_Emergency_and_Crisis/14605005 ↩︎ - 1800 Respect. 2024. Preventing work-induced stress and trauma. https://www.1800respect.org.au/resources-and-tools/work-induced-stress-and-trauma/preventing ↩︎

- World Health Organization. 2023. Stress. https://www.who.int/news-room/questions-and-answers/item/stress ↩︎

- Mental Health Foundation. 2023. Stress. https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/a-z-topics/stress ↩︎

- Mind. 2022. Stress. What is stress? https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/stress/what-is-stress/ ↩︎

- Mind. 2022. Stress. Signs and symptoms of stress. https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/stress/signs-and-symptoms-of-stress/ ↩︎

- Mind. 2022. Stress. Signs and symptoms of stress. https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/stress/signs-and-symptoms-of-stress/ ↩︎

- Mind. 2022. Stress. Signs and symptoms of stress. https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/stress/signs-and-symptoms-of-stress/ ↩︎

- Mind. 2022. Stress. What causes stress? https://www.mind.org.uk/information-support/types-of-mental-health-problems/stress/causes-of-stress/ ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. 2020. Depression: What is burnout? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/ ↩︎

- World Health Organization. 2024. Burn-out an “occupational phenomenon”. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/frequently-asked-questions/burn-out-an-occupational-phenomenon ↩︎

- National Library of Medicine. 2020. Depression: What is burnout? https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK279286/ ↩︎

- Maslach, Christina & Jackson, Susan. 1981. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. Journal of Organizational Behavior. 2. 99 – 113. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227634716_The_Measurement_of_Experienced_Burnout ↩︎

- Hilfe-Portal Sexueller Missbrauch. 2024. Trauma. https://www.hilfe-portal-missbrauch.de/en/good-to-know/trauma ↩︎

- PsychCentral. 2022. What Is Vicarious Trauma? https://psychcentral.com/health/vicarious-trauma ↩︎

- PsychCentral. 2022. What Is Vicarious Trauma? https://psychcentral.com/health/vicarious-trauma ↩︎

- Branson, D. C. 2019. Vicarious trauma, themes in research, and terminology: A review of literature. Traumatology, 25(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000161 ↩︎

- 1800 Respect. 2024. Checklist for work-induced stress and trauma. https://www.1800respect.org.au/resources-and-tools/work-induced-stress-and-trauma/checklist ↩︎