Videos

Relaxation techniques

Breathing exercises are the simplest path to inner calm. Practicing 15 minutes a day can achieve a significant reduction in your stress-related symptoms. Breathing is one function controlled by both the voluntary and involuntary nervous system, forming a bridge between our inner and outer selves. To use the technique, take several deep breaths and relax your body further with each breath.

Diaphragmatic breathing

By performing this exercise, you engage the diaphragm (the most important muscle of breathing), which increases airflow in your lungs.

Square breathing

Also known as box breathing or 4×4 breathing. This technique is the simplest form of mindful breathing and aims to return breathing to a normal rhythm in only a few minutes.

Progressive muscular relaxation

One of the most popular and easy-to-use methods to relax is by doing progressive muscular relaxation. This approach is useful for relaxing your body when your muscles are tense. The key is to become aware of tension and its corresponding state, relaxation, in each of the body’s muscle groups. First, tense a group of muscles so that they are tightly contracted. Hold the muscles in a state of extreme tension for a few seconds. Then, let the muscles relax normally. Next, consciously relax the muscles even further so that you become as relaxed as possible. By tensing your muscles first, you will find that you are able to relax your muscles more than you could if you simply tried to relax your muscles directly.

Experiment with this method by forming a fist and clenching your hand as tightly as you can for several seconds. Relax your hand to its previous state, then consciously relax it again so that it is as loose as possible. Following this practice, you should feel deep relaxation in your hand muscles.

Stress

The following video shows how stress affects our body:

Learn more about how stress affects the brain in particular in the following video:

The following video explains what happens to our body and brain when we skip sleep:

The following video explores the stages of how our memory stores information and how short-term stress impacts this process:

Burnout

Learn more about burnout in the following video:

Vicarious trauma

What is vicarious or work-induced trauma? This video introduces vicarious trauma and its possible effects on work and personal life. It also offers some techniques for addressing work-induced stress and trauma.

Case studies

Case study: Self-care in the health sector when dealing with cases of domestic violence

Emma is a physician working in the emergency department of an urban hospital. She regularly encounters victims of domestic violence who require medical assistance. In her role, she focuses on treating the physical injuries of the victims and ensuring they receive the necessary support.

As a physician, Emma is accustomed to working in stressful and emotionally taxing situations. She has learned to remain professional while attending to the needs of her patients. However, she often feels overwhelmed by the number of patients she must treat and the severe injuries she witnesses. She realises that she is increasingly feeling exhausted, often feeling guilty when she takes breaks or seeks assistance.

Tasks for reflection

(1) What challenges does Emma experience as a physician in the emergency department when working with victims of domestic violence?

(2) Why might it be challenging for healthcare professionals like Emma to engage in self-care practices? What factors might help Emma recognise her need for support, and how can she be encouraged to seek and accept help?

(3) How can neglecting self-care, such as not taking breaks at work, impact the performance and well-being of Emma?

(4) What steps could Emma take to improve her self-care?

(5) How could the work environment in the health sector be improved to help healthcare professionals like Emma enhance their self-care?

(6) What resources and support mechanisms could be helpful for healthcare professionals in similar situations to improve their self-care?

Examples

(1) Emma faces several challenges in practicing self-care, including:

- Emotional toll: Witnessing severe injuries and the trauma experienced by victims of domestic violence can be emotionally draining.

- High workload: The sheer number of patients and the urgency of their needs can be overwhelming.

- Pressure to perform: Maintaining a high standard of care while under pressure can be stressful.

- Feelings of helplessness: Emma might feel frustrated if she perceives that she cannot do enough to help her patients beyond their immediate physical injuries.

- Secondary trauma: Repeated exposure to victims’ stories and suffering can lead to secondary or vicarious trauma.

(2) Healthcare professionals like Emma might struggle with self-care due to:

- Perceived weakness: Seeking help or taking breaks may be perceived as a sign of weakness or inability to handle the job.

- Working culture: There is often an implicit expectation in the healthcare sector to prioritise patient care over personal needs.

- Time constraints: The demanding work in an emergency department leaves little time for breaks or self-care activities.

- Guilt: Emma might feel guilty for taking time for herself when patients need care.

Factors that could help Emma recognise her need for support include:

- Physical symptoms: Fatigue, headaches, or other stress-related symptoms.

- Psychological symptoms: Increased irritability, anxiety, or feeling detached from her work.

- Feedback from colleagues: Colleagues noticing changes in her behaviour or performance might prompt her to reflect on her well-being.

- Education and training: Awareness programmes about the importance of self-care and recognising burnout symptoms.

Emma can be encouraged to seek and accept help through:

- Supportive leadership: Encouragement from supervisors and a supportive work culture.

- Peer support: Building a network of colleagues who can offer mutual support and understanding.

- Access to professional help: Availability of counselling services.

(3) Neglecting self-care can significantly impact Emma’s performance and well-being, including:

- Physical health issues: Increased risk of illnesses due to stress and lack of rest.

- Mental health issues: Increased risk of anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues.

- Burnout: Emotional exhaustion, depersonalisation, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment.

- Decreased performance: Reduced ability to focus, make decisions, and provide care.

(4) Emma can take several steps to improve her self-care, such as:

- Regular breaks: Ensuring she takes regular breaks during her shifts to rest and recharge.

- Healthy lifestyle: Maintaining a healthy diet, exercising regularly, and getting enough sleep.

- Mindfulness practices: Engaging in mindfulness, meditation, or relaxation techniques to manage stress.

- Professional support: Seeking counselling or therapy to process her experiences and emotions.

- Boundaries: Setting boundaries to balance work and personal life effectively.

(5) To help healthcare professionals like Emma enhance their self-care, the work environment can be improved by:

- Creating a supportive culture: Encouraging open discussions about self-care and mental health.

- Flexible scheduling: Implementing flexible work schedules to allow for rest and recovery.

- Wellness programmes: Providing access to wellness programs, including fitness classes, mental health resources, and stress management workshops.

- Peer support systems: Establishing peer support groups where staff can share experiences and coping strategies.

- Leadership training: Training leaders to recognise signs of burnout and support their teams effectively.

(6) Resources and support mechanisms that could be beneficial for healthcare professionals include:

- Counselling and support services: Offering confidential counselling and support services.

- Professional counselling: Access to mental health professionals who specialise in working with healthcare workers.

- Training and workshops: Regular training on stress management, resilience, and self-care practices.

- Peer support groups: Facilitating peer support groups for sharing experiences and strategies.

- Sabbatical leaves: Providing opportunities for sabbatical leaves to allow for extended recovery time.

- Access to wellness facilities: Providing on-site wellness facilities such as gyms, relaxation rooms, and quiet spaces.

All sectors include different case studies. Visit Module 9 for the police, social sector and legal sector to find out more.

Factsheets

Knowledge assessment – Quiz

Quiz: Self-care

If you do not see a quiz here, please click here or use another browser.

Further training materials

Difficult situations in the context of domestic violence

Frontline responders play an important role in providing emotional support to victims, improving their safety, and providing legal assistance, but they routinely encounter unpredictable and complex situations and confront a range of challenges while providing support to victims.

Please click on the crosses to get more information.

Strategies on how to improve self-care

The following strategies are recommended to improve self-care at work.

Please click on the crosses to get more information.

Tasks for reflection

(1) Are you aware of the expectations you place on yourself in your professional role? How might these expectations be influencing your stress levels and overall well-being?

(2) Do you believe your expectations of yourself are realistic given the demands of your work?

(3) How do you perceive the impact of demanding work on your mental health? Are you acknowledging its impact, or do you tend to minimise or ignore it?

(4) What aspects of your professional life do you feel are within your control?

(5) Are you comfortable seeking help and support when needed?

(6) How do you approach stressful situations or obstacles in your work? Are you proactive in finding solutions, or do you tend to feel overwhelmed or stuck?

Self-assessment tool: Self-care

Self-care activities are things you do to maintain good health and improve well-being. You will find that many of these activities are things you already do as part of your normal routine.

In this self-assessment you will think about how frequently, you are performing different self-care activities. The goal of this assessment is to help you learn about your self-care needs by spotting patterns and recognising areas of your life that need more attention. There are no right or wrong answers on this assessment. There may be activities that you are not interested in, and other activities may not be included. This list is not comprehensive but serves as a starting point for thinking about your self-care needs.

Rate yourself, using the numerical scale: 5 = Frequently, 4 = Occasionally, 3 = Sometimes, 2 Never, 1 = It never even occurred to me

How often do you do the following activities?

Physical self-care

- Eat regularly (breakfast, lunch, and dinner)

- Eat healthfully

- Exercise, go for walks, garden, workout at the gym, lift weights, practice martial arts

- Get regular medical care for prevention

- Get medical care when needed

- Take time off when you are sick

- Get massages or other body work

- Do physical activity that is fun for you

- Take time to be sexual

- Get enough sleep

- Wear clothes you like

- Take vacations

- Take day trips or mini-vacations

- Get away from stressful technology (e.g., smartphones, email, social media)

Psychological self-care

- Make time for self-reflection

- Go to see a psychotherapist or counsellor

- Write in a journal

- Read literature unrelated to work

- Do something at which you are a beginner

- Take a step to decrease stress in your life

- Notice your inner experiences (e.g., dreams, thoughts, imagery, feelings)

- Let others know different aspects of you

- Engage in a new area (e.g., go to an art museum, performance, sports event exhibit, or other cultural event)

- Practice receiving from others

- Be curious

- Say no to extra responsibilities sometimes

- Spend time outdoors

Emotional self-care

- Spend time with others whose company you enjoy

- Stay in contact with important people in your life

- Treat yourself kindly (e.g., by using supportive inner dialogue or self-talk)

- Feel proud of yourself

- Reread favourite books, watch favourite movies

- Identify and seek out comforting activities, objects, people, relationships, and places

- Allow yourself to cry

- Find things that make you laugh

- Express your outrage in a constructive way

- Play with children

Spiritual self-care

- Make time for prayer, meditation, and reflection

- Spend time in nature

- Participate in a spiritual gathering, community, or group

- Be open to inspiration

- Cherish your optimism and hope

- Be aware of non-tangible, nonmaterial aspects of life

- Be open to mystery, to not knowing

- Identify what is meaningful to you and notice its place in your life

- Sing

- Express gratitude

- Celebrate milestones with rituals that are meaningful to you

- Remember and memorialise loved ones who are dead

- Nurture others

- Have awe-filled experiences

- Contribute to, or participate in, causes you believe in

- Read inspirational literature

- Listen to inspiring music

Professional self-care

- Take time to eat lunch

- Take time to chat with colleagues

- Make time to complete tasks

- Identity projects or tasks that are exciting, growth promoting, and rewarding

- Set limits with colleagues and clients

- Balance your caseload so that no one day is “too much”

- Arrange your workspace so that it is comfortable and comforting

- Get regular supervision or consultation

- Negotiate for your needs

- Have a peer support group

Tasks for reflection

Once you have completed the self-assessment, reflect on the following questions:

(1) Were there any surprises? Did the assessment present any new ideas that you had not thought of before?

(2) Which activities seem like they would be more of a burden than a benefit to you?

(3) What are you already doing to practice self-care in the physical, psychological, emotional, spiritual, and professional realms?

(4) Of the activities you are not doing now, which particularly sparks your interest? How might you incorporate them into your life sometime in the future?

(5) What is one activity or practice you would like to try starting now or as soon as possible?

Stress

Stress can occur in different areas of our lives. These may include:

Please click on the crosses to get more information.

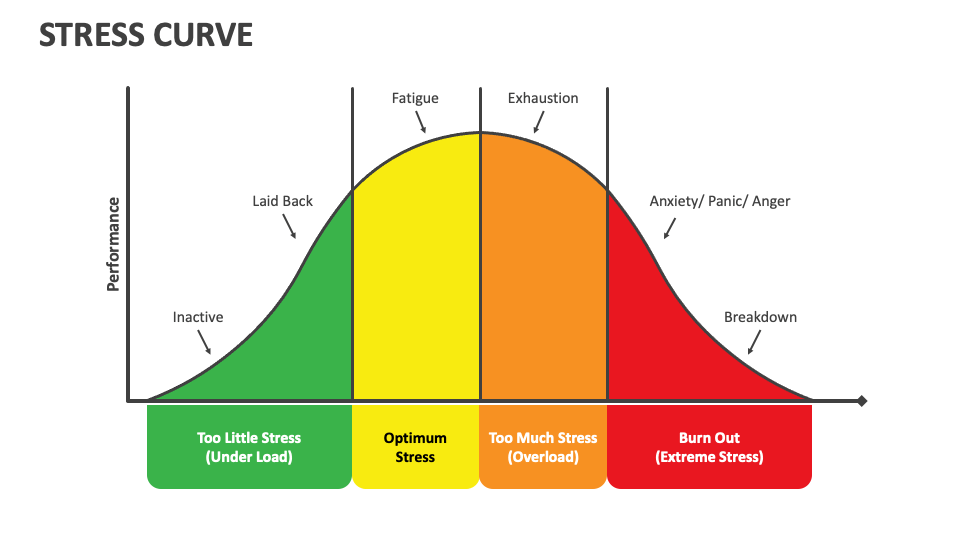

The following illustration shows the progression of a stress curve from too little stress to burnout:

Too little stress

- Inactive: In this phase, stress levels are very low. Individuals might feel bored, disengaged, and lack motivation. There is insufficient pressure to stimulate action or focus.

- Laid back: As stress levels increase slightly, individuals may feel relaxed but still lack the drive to perform. There is minimal urgency or challenge to spur productivity.

Optimum stress

- Fatigue: When stress reaches a moderate level, individuals begin to experience increased energy and focus. This phase is marked by heightened alertness and motivation, leading to high performance. This is the zone of optimal performance where stress acts as a positive force.

Too much stress

- Exhaustion: Beyond the optimal point, stress levels become too high, causing performance to decline. Individuals may experience physical and mental exhaustion, leading to decreased productivity. The stress starts to take a toll on the body and mind, making it difficult to maintain high performance.

Burnout

- Anxiety/Anger/Panic: At this stage, prolonged high stress leads to severe emotional and psychological effects. Individuals may experience anxiety, anger, or panic, significantly impairing their ability to function.

- Breakdown: Finally, chronic stress results in a complete breakdown. This phase is characterised by physical, emotional, and mental exhaustion, where individuals are unable to perform or cope with stress. It may manifest as severe fatigue, depression, or total withdrawal from activities.

Vicarious trauma

The following checklist contains more signs to be aware of. The things on the list do not necessarily mean that you are suffering from burnout or vicarious trauma. An answer of “yes” to any of the questions can alert you to the need to speak to someone to receive support.

Checklist for burnout and vicarious trauma

- Are your relationships with close friends, family, children, or partners changing for the worse?

- Are you finding yourself irritable, anxious, agitated or “snapping” more frequently than usual?

- Are you worried about your work performance?

- Are you avoiding, or getting anxious about engaging with work, clients, or patients?

- Do you notice mood swings or feel your moods are sometimes out of your control?

- Are you feeling flat, sad, lacking energy, overtired for no reason, or as though you are “spacing out” from things around you when you are stressed?

- Are you getting run down or catching more colds or infections than usual?

- Do you feel unsafe or overly anxious about your safety?

- Are you self-soothing in ways that might be numbing or can cause you increased stress later, such as mindless eating, alcohol or substance use, or smoking?

- Do you feel you have lost hope, or that there is little “goodness” in humanity?

- Do you have nightmares, poor sleep, intrusive thoughts, or images that are upsetting?

- Check your breathing throughout the day — is it more often than above 15 breaths per minute? Or below seven? Is this linked to thinking about work, or other stress triggers?